News

BN Film Review: Daniel Effiong’s Crimson by Ainehi Edoro

Daniel Effiong’s Crimson, recently nominated for the 2014 Afrinolly Shortfilm Competion, breaks all the Nollywood rules of filmmaking. {Click Here To Vote}

Daniel Effiong’s Crimson, recently nominated for the 2014 Afrinolly Shortfilm Competion, breaks all the Nollywood rules of filmmaking. {Click Here To Vote}

Before I go on, I want to make it clear that I’m not trying to knock the Nollywood hustle. As an innovative financial model for filmmaking, Nollywood is genius. It taught the rest of the world how to create a viable film industry in the absence of a traditional distribution system and big budget. But Nollywood is also a technique of filmmaking—lengthy dialogue, overacting, exaggerated gestures, shouting, sloppy editing, amateur camera work, cringe-worthy music, and so on. That’s the Nollywood that Effiong’s psychological thriller breaks away from.

Take dialogue for example. The average film viewer can sense that film is a medium that tells stories through images. This may seem surprising, but dialogue is not where the heart of a good film lies. After all until the 1920s, silent films were the norm. Viewers were quite content to sit through an hour of muted gestures. Filmmaking is about relying on images and sound to express emotion and the inner thoughts of characters. A character does not have to tell us that they are sad. A combination of lighting, set design, camera angle, editing and of course the acting conveys the inner states of mind of a character. Dialogue is like the cherry on top. It adds to the cake’s perfection, but it is not where the true beauty lies. Of course, Nollywood has doggedly refused to come to terms with this very basic idea of how filmmaking works.

Crimson is different. Effiong knows he has a set of delicate stories in his hands. The third episode is loosely based on one of the SSS interrogations that took place shortly before Dele Giwa’s assassination. The entire 12 minutes of the short film is set in an interrogation cell where Giwa confronts Inspector Akin, the nemesis of all enemies of state. Effiong could have gone the Nollywood route and made it all dramatic—shouting, beating, crying, bulging eyes, growling and so on. He doesn’t because he wants every second of that 12 minutes to unfold into an intense exploration into the psychology of police interrogation.

An interrogation is a psychological affair. It is a mind game. A man can do more damage breaking convictions than breaking bones. Akin’s objective is to get Giwa to stop writing bad things about the government. But Akin is not a crude thug. He knows that to bend the will of a man like Giwa takes a peculiar kind of violence. Giwa has the assurance of morality on his side. He thinks that in outing the government, he is not only standing on the side of truth and justice but also saving a beloved country. Akin knows all this. Akin also knows that there is a part of Giwa that is scared shitless. Treason is not a soft crime. Death by hanging is the logical outcome. Besides, every man has his price in the sense that every man has this one possession—a child, a lover, a lifestyle, etc.— that they will not loose for anything in the world. Effiong’s objective is to show us how Akin manipulates all these variables to get Giwa to admit to crimes that he may or may not have committed.

Maybe that’s why Crimson is not a story packed full of drama. It’s a story about two minds at war. We know that Akin will crush Giwa’s resistance and make him surrender, but how he does it is a beauty to behold. The mind games, bluffs, deceits, false hopes, threats, treats—Akin’s bag of tricks is bottomless. We can’t help but enjoy the thrill—not without feeling guilty—of watching Akin break Giwa’s resolve. A film like this cannot depend solely on dialogue. If the goal is to reveal deep psychological insecurities and manipulation, something more than dialogue is needed. After all, the deepest, darkest feelings are the least translatable into words.

Besides, Effiong wants his viewers to be conflicted. He wants them to come out with a complicated sense of good versus evil. In the Nigerian law code and in the bible, the difference between good and bad might appear to be clear, but not so in real life. Things get mixed up. You begin the film expecting to feel sorry for Giwa, and you do. You sympathize with his predicament. Effiong does a good job of making you experience Giwa’s anguish vicariously. What you don’t expect is that you’d fall in love with Akin. I like to think of him as a modern-day Mephistopheles. Of course you are drawn to the fact that he looks razor-sharp and dapper. You imagine him has some kind of African and urban version of James Bond. But you also love his mind, as dark and twisted as it is. He scares you, but you reassure yourself that as long as you meet him at a cocktail party and not in an interrogation cell, he could actually be a lot of fun. How do you translate all these complex and nuanced emotions and feelings into a movie? Effiong returns to the basics of filmmaking and lets images and sound do the bulk of the translation.

The surprising thing is that a film that begins by telling its story through a careful orchestration of sounds and images hardly ever goes wrong with dialogue. The dialogue in Crimson sits somewhere between witty and poetic. Short and choreographed retorts that are packed full of meaning convey much of the intensity of the film. Another reason Crimson is a joy to watch is the nuanced acting. Seun Ajayi is sublime as Inspector Akin. Behind the pearl white smile, the Nigerian accent modulated to perfection, the obsessive smoking, you sense a mysterious man. Ajayi’s acting is both precise and effortless in the way it hints at a man with a past so dark that he is forced to enlist his demons in the interrogator’s search for “truth.” O. C. Ukeje’s performance as Dele Giwa is also stellar. Both actors are economical with their gestures because they know the viewer is not relying solely on their acting to connect with the story emotionally. In Crimson, every little body or facial movement counts and goes a long way in conveying the characters inner state and the mood of the scene. An eye movement, a smirk, a squint, a smile, a muffled grunt, bent shoulders, even silence is all we need to register shifts in emotional states. But that’s because the appropriate sound, the right camera angle, and the perfect set have done all the ground work.

While Nollywood is taking its time deciding whether to shoot films—tell stories through images and sounds—or write novels, Daniel Effiong is giving us a beautiful specimen of the future of Nigerian filmmaking. With filmmakers like Effiong, the future is guaranteed to be great.

The second episode of Crimson–“A Cup of Tea”–has been shortlisted for the 2014 Afrinolly Short Film Competition. {Click Here To Vote}

__________________________________________________________________________

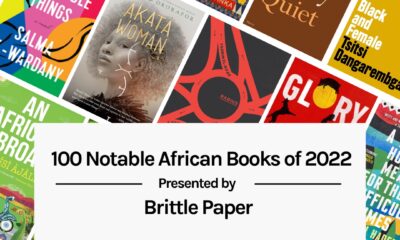

Ainehi Edoro is a doctoral student of literature at Duke University where she studies African novels. She is also the founder and editor of the African literary blog called Brittle Paper.