Features

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: CJ Obasi’s ‘O-Town’ is Overindulgent but Brilliant

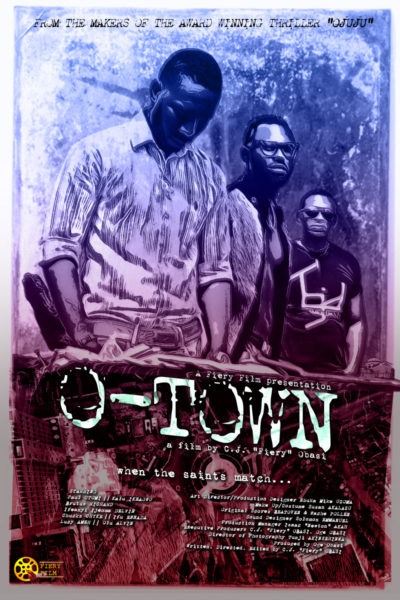

In O-Town, director CJ Obasi proves he is his own greatest subject. His earlier film was a zombie flick. Perhaps awed by the audacity of the endeavour, prize juries handed him awards. This time he has helmed a gangster story set in Southeast Nigeria. The town is O-Town, a lightly fictionalised version of Owerri, the filmmaker’s childhood city. By his own admission, the events covered are semi-autobiographical. Given the film’s violence, hopefully, this admission means what he observed rather than what he lived.

In O-Town, director CJ Obasi proves he is his own greatest subject. His earlier film was a zombie flick. Perhaps awed by the audacity of the endeavour, prize juries handed him awards. This time he has helmed a gangster story set in Southeast Nigeria. The town is O-Town, a lightly fictionalised version of Owerri, the filmmaker’s childhood city. By his own admission, the events covered are semi-autobiographical. Given the film’s violence, hopefully, this admission means what he observed rather than what he lived.

O-Town follows small time hustler Peace, who has quite the ambition: he wants to be head of the streets. ‘You want to be me,’ the street kingpin Chairman (played with relish by Kalu Ikeagwu) tells him when they meet. Paul Utomi as Peace is convincing, his face dark and hard for the role, so that his smile and open mouth cast an immediate relief against the rest of his face. Onscreen he is lean and lightly muscular and commands a presence that makes Peace believable in anger and in anguish. The camera has a lot of fun with the man’s face. Peace has a run-in with an artist known as The Artist. The Artist comes out poorly and seeks revenge. The trouble, however, is that Peace has formed an alliance with The Chairman. From that point onward there is big trouble for all involved, as vengeance, counter-vengeance and ambition all come to play in a small town.

This is good enough to establish a gangster story but it’s insufficient for Obasi. He is a lover of excess and although this is unmistakably a Nigerian film, Obasi is working from a rich template of American gangster/mobster movies. Brain DePalma’s Scarface, Coppola’s Godfather, Reservoir Dog-era Tarantino. And as such he has his characters speak near-perfect ‘American’. Many of his major characters carry no regional accent although they all have the small-town malady of thinking highly of personal slights. A small injustice is made larger when everyone and their mother knows you. Add the regular aggression of gangsters and this provides the motivation for all of the violence that shows up in O-Town. The political ramifications for such a film at this time in Nigeria’s history is anyone’s guess. And at the premiere of the film at the Africa international Film Festival, an actor expressed worry: what if this film is shown abroad?

It can’t be pretty for foreign audiences with a certain view of Nigeria. And yet, that is an extra-cinematic concern, at least for Obasi whose focus is what is on the screen. For him the screen is a mirror, not for his face but for his fantasies. Credit to him, he gives his characters the first two acts.

But he interrupts the third, tarnishing his own effort with narcissism, imposing himself on his characters. (A character is actually named Fiery, the director’s nickname.) It is not the first time an artist kills his demons while his audience watches helplessly but it’s probably the first time it is done accompanied by some inane, incoherent philosophy delivered by a voice over. This is the trouble with mavericks, they have a need to push their own agenda without creative assistance. (Obasi writes and directs.)

Before we get to that third act, though, Obasi has served a praiseworthy lesson in manipulating the elements, which is still a feat in Nollywood; transferring what he’s learned from other films and their cinematography; and being badass and knowing it. He uses light and shade brilliantly and deftly employs black humour, a quirk that connects his film to Kenneth Gyang’s Confusion Na Wa.

Obasi, it becomes apparent, is convinced of his own brilliance and wants you to know it. Unfortunately, the cinema culture of his immediate audience isn’t as sophisticated to see that beneath the scenic superfluity and indulgent stylisations of O-Town, is the work of an inventive filmmaker, one with a clear sense of what he wants onscreen and the means to achieving same. There are coloured lights, singing monologues, and layered flashbacks. If Obasi considered his audience, he never shows it. For the two hours our director is bent on his vision not once does he look over his shoulder to see if anyone is following—does he even care? His audience, he supposes, is as cinematically learned as he is. And if not, too bad for them. While this may be a sign of dedication, it is also a symptom of self-absorption. (O-Town could easily mean Obasi-Town.) He seems unaware that a projection of his grandeur will break his own heart because anyone erecting monuments to his own intelligence and learning is certain to be disappointed when no one else agrees with the self-assessment, or worse: when everyone else is indifferent.

When that heartbreak comes, his directing peers won’t protect him. Why? Because he has made a movie they don’t love in a manner they would love to adapt. The industry has broken a few of our younger filmmakers and now they have to make films assured of a return—which in practice means art on a financier’s whims. Following his own vision, Obasi has made O-Town in a style his contemporaries might wish they could adapt, if only to input their own idiosyncrasy. But then they want to continue making movies easily—a detail that means they have to follow the market.

What does this mean for Obasi? Again, heartbreak. He’ll be acclaimed for his hyper-stylised filmmaking, for the breadth of his self-conscious references, and for his bravado but he’ll hardly earn a living off it. As our director himself has admitted, he couldn’t convert the goodwill and good reviews of his earlier film Ojuju into funding for O-Town. Eventually, he pulled it off, excesses and all, with what looks like an extremely low budget. Yet he has made a good film, cutting out his flamboyance and a hunk of screen time.

In succeeding despite constraints, Obasi proves he is tenacious, a quality required for artists in this clime. And his talent is obvious from the film itself. Talent and tenacity he has; subtract his excesses and we have a fine filmmaker. One that, barring extreme fortune, is destined for heartbreak, but also one for whom a level of greatness is within reach.

That is enough reason to watch this filmmaker. Start by seeing O-Town. Maybe twice.