Features

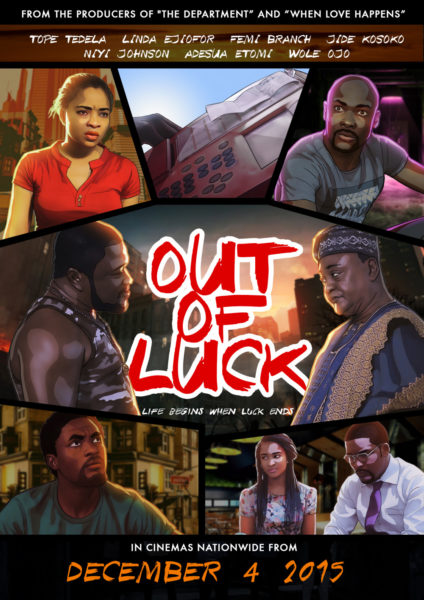

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: ‘Out of Luck’ Conjures Disappointment From Promise

Nothing prepares you for the disappointment that is Out of Luck. Not the title, that slick 3-word, 3-syllabled compact phrasing. Not the trailer, which having seen the film, I think used up all of the good moments. And not the premise: a lottery operator has to pay a drug boss money the latter hasn’t won.

Nothing prepares you for the disappointment that is Out of Luck. Not the title, that slick 3-word, 3-syllabled compact phrasing. Not the trailer, which having seen the film, I think used up all of the good moments. And not the premise: a lottery operator has to pay a drug boss money the latter hasn’t won.

How has Out of Luck, directed by Niyi Akinmolayan, managed to dredge disappointment from promise?

Before anything else, it’s a failure of atmosphere. Somehow the film leaves a creation of atmosphere to its surroundings, primarily a beer parlour and a drug den. A great choice of location worked for the Lagos life Oriahi’s Taxi Driver aimed to portray, but even there, the photography amplified what was. In Out of Luck the photography ruins what is.

Out of Luck has three main characters. Dapo is the lottery operator who gets into trouble when an issue with timing means a drug boss receives no returns on a correct sequence of numbers. Played by Tope Tedela, who receives a low haircut so his soft looks fits with the environment, Dapo is in love with Halima (Linda Ejiofor). Halima is the belle of the area; onscreen she bestows a kiss on the head of one old man and before her relationship with Dapo, has bestowed her love on drug boss Innocent (Femi Branch). Although framed as a race to pay (and/or escape) a drug boss, this love triangle is Out of Luck’s true subject—what, in academic circles, may be called a research question: What happens when a woman goes against her evolutionary need for security, opting for the aesthetic ideal of a weak, good looking mate? Derailed by its gangster aspirations, it isn’t a question a question the film answers well.

Innocent growls through the film’s duration, calling Dapo ‘Fine Boy’. Implicit in the nickname is a sneering, ‘Boy, you are spineless.’ Dapo knows Innocent is right. And to disprove Innocent’s assertion, Dapo decides to be brave. Being forced to man-up while a love interest watches is a familiar spot for non-cavemen. It is the reason a new driver in Oriahi’s Taxi Driver is told to target girls in company of their boyfriends—in that arrangement men fork out more money for cab fare. It is also why few men cry before their women. Of course, Dapo’s other problem is that he lives in Lagos, a city where every male in the street is a caveman or has to appear to be so to survive. (Was there any way to traverse the old Oshodi at night without summoning unknown powers to look menacing?) For Dapo, it’s down to two options: flee Lagos or do something criminally brave. You can guess what a threatened manhood makes him do. Halima, however, thinks different: She wants to beg Dapo’s estranged brother for money.

Thus a domestic subplot emerges. Thus a different set of actors appear. Seun (Wole Ojo) as Dapo’s brother. Bisola (Adesua Etomi) as Seun’s wife. Both characters are rich; sadly, both actors are unsuited. They form an unflattering contrast. Ojo is aloof, as is his acting wont. Etomi is over enthusiastic — the actress came from stage and appears unaware that what may be powerful onstage is hammy onscreen. When we meet Bisola, she’s an eager package bouncing, like a yoyo with a nervous system, to please a brother-in-law we have no cause to believe she knew existed. Later she’s a love guru. Nollywood, as shown here, has gone from making witches of wives to having them as goody-two-shoes. (Feminists should have quite the day with this paradigm.)

As Bisola/Etomi is too present and Seun/Ojo is barely there, the couple prove you don’t need great chemistry to have a rich marriage, nor do you need to be suitable to get roles. A pair of pretty faces works in both instances.

Out of Luck has its eyes trained on Hollywood even as it gropes at lower class lives in Lagos. In some hands, this manoeuvring may work, especially when the filmmaker shows an understanding of the local content and the foreign form. But Out of Luck shows an admiration, not an understanding, of Hollywood tropes. The result makes for jarring viewing. In one instance, Innocent—embodied by a stocky Femi Branch savouring his role as American thug in a Nigerian slum—shoots a thieving half-clad employee so that she falls against a glass door. It’s an overdone Hollywood scene unduly overwrought by Out of Luck.

Although a story about a romantic triangle, Out of Luck apes the wrong Hollywood genre by focusing on faux-nourish aspects. The prime example comes when Innocent tries to barter Halima. Give me Halima and I’ll forget what you owe, he says to Dapo. Wrong move. As everyone knows, the woman is bound to disagree and the weak man hates being a weaker jerk. Rather than copy Hollywood action movies, there is the example of John Gage (Robert Redford) in 1993’s Indecent Proposal. There the proposition was devoid of guns: Give me one night with your wife and you can have a million. (Of course you could say nineties’ Redford plus a million dollars is a different deal from Branch’s potbelly and a million Naira. But then power is a useful aphrodisiac.)

Still, Hollywood won’t help this one. Mostly because Out of Luck looks and sounds amateur. As said, the film’s photography hardly works. Ditto its sound. Perhaps courtesy of misplaced microphones and flawed design, the film’s sound is all over the place. The sounds of violence are especially poor.

The worst is saved for last. Out of Luck fields a last scene copied and pasted from shabby Hollywood films. It is a very familiar sequence for anyone who saw a fair share of Hollywood in the nineties. I refer to the one where a struggle among two or more characters leads to a weapon spilling unto the hands of another character, usually a woman, a child—or, in general, the most unqualified character around.

At that point, the viewer blurts a sigh: She’s seen it done before. She’s also seen it done better. Way better.