Features

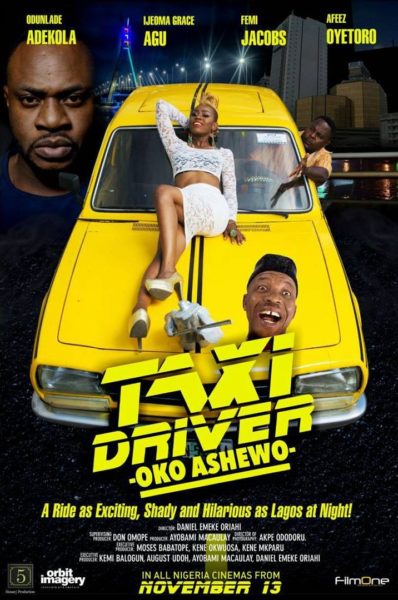

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: Daniel Oriahi’s Taxi Driver (Oko Ashewo) is an Edgy Crowd Pleaser

Lagos is a scary place and no one should tell you different. Actually, no one tells you different. Not the books like Toni Kan’s Night of the Creaking Bed and Ayo Sogunro‘s The Wonderful Life of Senator Boniface and other Sorry Tales. And not the 1990s comedy Lagos Na Wa. Writers of these fare are realists perhaps. But the message has been passed across so many times that any artist presenting Lagos as a sunny, happy place would be subverting an entire genre.

Lagos is a scary place and no one should tell you different. Actually, no one tells you different. Not the books like Toni Kan’s Night of the Creaking Bed and Ayo Sogunro‘s The Wonderful Life of Senator Boniface and other Sorry Tales. And not the 1990s comedy Lagos Na Wa. Writers of these fare are realists perhaps. But the message has been passed across so many times that any artist presenting Lagos as a sunny, happy place would be subverting an entire genre.

Yet despite the abundant efforts of our artists, the city keeps attracting aspirant and dreamy characters. Lagos may inspire fear in the minds of our artists but their characters believe the juice is worth the squeeze.

Daniel Emeke Oriahi’s Taxi Driver (Oko Ashewo) is the latest inclusion to the inexhaustible Lagos-is-Dangerous corpus.

He sets his new film at night, doubling the menace, tripling the inevitability of terror. Night, as any film lover knows, is when the monsters come out. Only, in Lagos these monsters are human, and every bit as desperate to survive as their victims. The myth sold on the streets is that all parts are needed for Lagos to thrive. Clearly, no one who has lost their phone, car or innocence agrees. Still the myth prevails. ‘Lagos needs people like me for balance,’ a malevolent character tells Taxi Driver’s hero.

Our hero is Adigun. With his shaky grasp of English and lovelorn puppy look, Adigun (Femi Jacobs) is more anti-hero than hero. Coming from Ibadan to Lagos, Adigun seeks a livelihood. Somewhat vaguely, he also seeks closure on his relationship with his deceased taxi-driving dad. The old man left Adigun’s mother to come to Lagos and never quite returned. So when we meet Adigun, he is a man of significant age seeking that most unobtainable of things: a father in Lagos. A swindler you’ll get, a smiling thief you’ll get. But no one gets a parent in Lagos.

Fortunately, Adigun’s father is survived by a friend (Odunlade Adekola) who shows our hero the ropes and tells him a few tricks of the taxi trade: work more at night, carry call girls, carry girls in company of their boyfriends. Men in Lagos must know a thing or two about this last trick.

If you think the city would swallow Adigun’s quest, you’ll be correct. If you think this is a drama you’ll be wrong by half. In his previous film Misfit, director Oriahi showed he is adept at wringing terror from rather mundane circumstances. Here, he shows that that ability abides. Adigun’s quest becomes the springboard for events that are thrilling for his audience and harrowing for the characters.

Taxi Driver is looking at the big terrors but it is an error of perspective. Lagos hardly delivers big terrors daily. What is truly terrifying in Lagos are the smaller terrors that erase the illusion of a city’s normalcy: the regular violence of commuting, the noise, shylock landlords, and the drudgery of traffic hold ups. Oriahi is working on a big canvas and that possibly excludes these smaller details. In any case, these things are mostly unfilmmable. Ironically, while Taxi Driver sets out for the big terrors it is the smaller bits, the dialogue primarily, that gives this film its pleasures. It opens with the cliché of a stammering character and then relaxes into some of the most authentically Nigerian dialogue, delivered in Yoruba and pidgin, heard on the big screen.

The notion of authenticity carries into the subtitles, where the producers have opted for pidgin instead of the usual English translations. Most film lovers want films from their country to have international appeal, but there is something to be said for cultivating the home base. It is more symbolic gesture than a practical one—chances are if you can read those pidgin subs you can read English as well.

Snobs will be pissed but it appears producers were shocked by the success of 30 Days in Atlanta and have come to realise that there are a lot more pidgin speakers than people with the Received Pronunciation in Nigeria.

Before that film filmmakers put mostly middle class characters on the screen. 30 Days offered an alternative: put some instantly recognisable Nigerian character and see what happens. What happened was a massive box-office return. Since then we have had films striving to consider the underclass and their ways.

Oriahi does better than most of the newer films looking to show the working class. He doesn’t condescend. And Director of Photography Akpe Ododoru matches his director’s aims with subtle shifts in perspective in some scenes. Oriahi chooses the right interiors to shoot. (Adigun’s Lagos residence has rooms so claustrophobic a character almost chokes to death sitting alone.) The setting is clearly Lagos Island and on several occasions the fence of the popular Freedom Park is illuminated by Adigun’s headlights. This makes you think: could a film about the menace of Lagos be set on the Mainland? Might such a film not be more authentic? Imagine rundown areas in Ketu, Oshodi and Mile 12 lit up on the big screen. That film practically shoots itself. Granted that the filmmakers would have to survive the experience first.

Taxi Driver is gripping and moves briskly as a film set in a Lagos vehicle should. But an expositional scene intended to give the lead female character (Ijeoma Grace Agu) a back story deadens the momentum. It recovers and heads towards mayhem and several twists in a key scene. At that point you may think Taxi Driver is headed for tragedy. It doesn’t and that is the film’s tragedy.

Cinema chain, FilmOne, receives executive production credit and must have desired and demanded a crowd-pleaser. Tragedy would send the audience screaming at the screen and put paid to the film’s commercial potential. In any case Nigerian filmmaking remains in sync with the country’s Pentecostal belief in optimism. And therein lies a strangeness: Heroes die or are forgotten in Nigeria but our filmmaking realists can’t quite bring themselves to do same in their art. They seem to want to compensate their audience for all the trouble that is the average Nigerian life. Oriahi follows suit. His need to crowd-please wins over the film’s edginess in his story. Luckily, Taxi Driver is delivered from sentimentality by strong lead performances and by that middlebrow edginess that is later disavowed.

Oriahi caters to the audience. His film follows the joy. And the Lagos-is-Dangerous corpus lives on.