Features

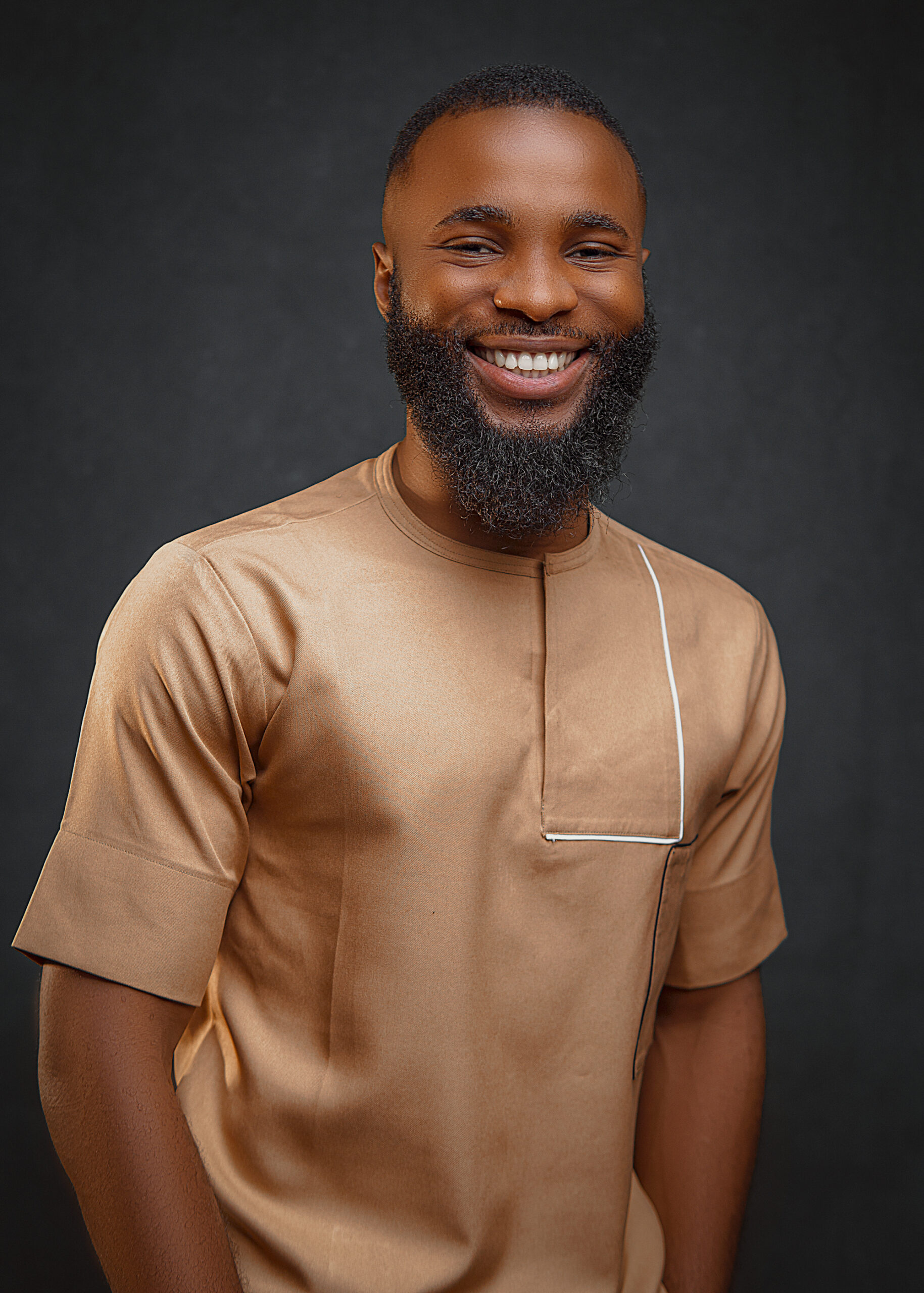

Victor Bello’s Almajiri Scholar Scheme is Changing The Lives of Children in Jos

One of them narrated that he was passing through a fancy restaurant when someone offered to give him food. When he opened it, all he found there were bones. The child felt insulted and said he was going to eat a full chicken in that restaurant someday.

Before joining the Almajiri Scholar Scheme, Hassan (this name is a pseudonym) dreamed of becoming a kidnapper. Hassan grew up as an Almajiri boy – little children entrusted in the care of an Islamic leader, splattered around the streets of some Northern states, bowl in hands and begging for alms. Without access to formal education, he believed kidnapping, which is fast becoming a booming business in Nigeria, would be his source of wealth. This was until Victor Bello, the founder of an Almajiri Scholar Scheme, found him on the streets of Jos, Plateau State.

The Almajiri system prioritises Arabic education over Western education. From a young age, children are sent to their teachers’ homes to learn. It is a system of Islamic education practised in Northern Nigeria that involves young boys, referred to as Almajiri and young girls, known as Almajira, with the plural of both being Almajirai. This system sees parents entrusting their children’s upbringing and education to Islamic schools, often relinquishing their parental responsibilities to the underfunded school authorities. On most occasions, when these authorities are unable to feed them, the children are dispersed into the streets to beg.

Hassan’s story, along with many others he witnessed growing up in Kaduna, influenced Victor Bello’s decision to start the Almajiri Scholar Scheme in March 2022 with the goal of exposing these children to literacy and Western education.

Victor Bello had his first encounter with the Almajiri students in Kaduna and became curious about why children his age were restricted from acquiring a formal education. When he became an undergraduate at the University of Jos, he tried introducing Almajiri children to formal education but faced pushback from the community. In 2020, during Ramadan, he provided Iftar meals for about 15 children and used the opportunity to introduce his idea to the community. They declined, not only because Victor was a Christian but because the community had a rigid resistance towards formal education, terming it ‘Western’.

In 2021, during Ramadan, he repeated what he had done the previous year but on a larger scale. He took the iftar meals to the Jos central mosque where he met the leader of Almajiri education in the state, who liked his idea. This leader introduced him to Mallam Habali, who was in charge of a group of Almajiri children in the Angwan Rogo community.

When Victor started, he was focused on expanding to as many communities as he could in Jos. However, after the first month, he realised how demanding the project was going to be. He funds the project from his pocket, with some volunteers who are willing to teach the students for free.

“I really didn’t know that I was going to spend my time and money like that until I ventured into the project fully,” Victor reflects. “I think after six months, I said, ‘nah, I need to just focus more on these children first’, because even if I want to educate all the Almajiris in Jos, it’s still not enough. It’s still not up 10% of all the Almajiris in Nigeria.” According to UNICEF, there are 18.3 million out-of-school children in Nigeria, and 81% are estimated to belong to the Almajiri system.

Due to a lack of financial capability and resources to expand, Victor said he’s committed to training the students he currently has at the Almajiri Scholar Scheme. “I have 80 students now, which is a very good number. I should invest more in these children I have instead of expanding. When I have built my capacity very well, financially and otherwise, I will think of expanding. But for now, I’ll focus more on the ones I have with me.”

Proud Moments

Despite Victor’s Almajiri Scholar Scheme, the children continue their Arabic learning with their Mallam. One day, the Mallam told Victor that the children sing the letters of the alphabet and the figures most of the time now. This knowledge made Victor proud, but it did not compare to when he travelled out of Jos and his students called him using their Mallam’s phone, saying, “Uncle Victor, please, don’t leave us. What you’re doing for us, no one has done before.”

“It made me realise that I’m actually on the right path, because sometimes I ask myself, ‘Am I really making an impact? Or am I just too emotional about the whole Almajiri thing?’ Sometimes I doubt the whole thing I’m doing, so that was really encouraging for me. It’s one of my proudest moments in this project.”

But it wasn’t just that one incident. Once, after a class, Victor gathered the students around to mention some Northern successful people they could look up to, to dissuade them from societal vices like kidnapping. After the encouragement, he asked the students to tell him about themselves and talk about their lives outside the scheme training. One of them narrated that he was passing through a fancy restaurant when someone offered to give him food. When he opened it, all he found there were bones. The child felt insulted and said he was going to eat a full chicken in that restaurant someday.

It was one of the most touching moments for Victor, one that swiftly turned into a happy one. “When he said that, I almost cried. I said, ‘You know what? All of you should get ready. Next week, we are going to that restaurant.’ It is one of the biggest restaurants in Jos. They call it Bacardi. We went there and they had good food. They never stopped talking about that day. Even if I don’t feel fulfilled, I feel so happy whenever I think of that day. I feel so excited because these are children that I have seen on the streets since my childhood.”