Features

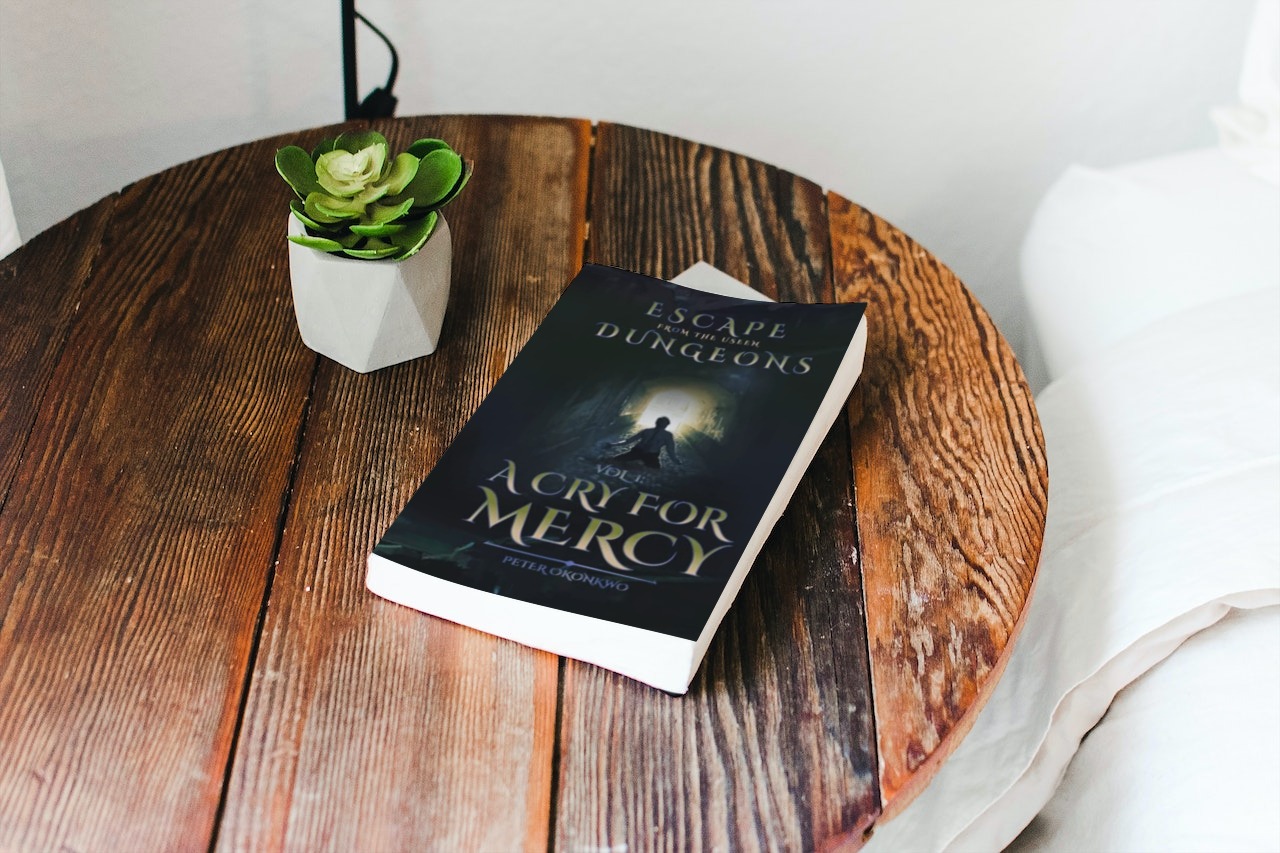

BN Book Review: A Cry for Mercy by Peter Okwonkwo | Review By Roseline Mgbodichimma

…a manual for believing in the divine while still being human and flawed in this wild world.

Can a poet truly repent, or a narrator wrestle with God and win? Is poetry and prayer one and the same? In Peter Okonkwo‘s ‘‘A Cry For Mercy’’, we see that in a shared space of questioning and deep seeking, the lines blur between poetry and prayer, revealing how both can arise from the depths and platitudes of unanswered questions.

An author of six poetry collections, Okonkwo considers himself a spiritual philosopher and it is not hard to see why. ‘‘A Cry For Mercy’’ is premised on the perceived sovereignty of the Christian God and what belief looks like for believers in diverse stages of life – the good, the bad, the ugly. Within the book’s pages, life’s most profound struggles and sorrows are distilled into poignant questions – questions that serve as a cathartic release, a passionate plea, and a bold inquiry into the divine. Through letters and texts, the poet cries out for answers, threatening to burst the heavens wide open with queries. Spanning over a hundred pages, this work is an unflinching case for wailing, a testament to the possibility of questioning divine authority. This collection is not for the faint of heart or those who shy away from challenging the religious status quo.

In the opening poem, ‘‘A Cry For Mercy’’, the line “Dear merciful God, where is your face?” captures the speaker’s desperate plea for divine guidance. This cry for help reveals the daunting struggle to find answers within the limitations of human understanding, and the longing for a more personal and relatable God. Using the imagery of tears, sleeplessness, and abandonment, the poet writes that mercy and compassion are fundamentally human qualities, making the need to personify God all the more urgent.

Like many poems in this collection, ‘‘Longing For Help’’ is a raw and honest expression of desperation, with a palpable and heartfelt intensity. The metaphor of transforming ‘‘the days of my labour into history’’ portrays a deep desire for meaningful change and transformation. Moreover, the lines ‘‘Do not let me die / without an impact, / like a snake that crawls / upon a rocky part. / Exchange my impediments…’’ reveals a pressing need to leave a lasting mark in the world, exposing the speaker’s desperation to overcome obstacles and make a significant difference.

The persona in the poem ‘‘Who is at Fault?’’ feels trapped by circumstances and struggles to understand why they’re suffering despite their prayers and efforts. The persona in ‘‘A Soul at War’’ is torn between their sinful nature and desire for righteousness, pleading for divine intervention. Both poems express deep emotional pain, frustration, and despair. In ‘‘A Conversation with Obstacle’’, we sense the speaker’s relationship with adversity. The personification of Obstacle as a conversational partner gives the poem a kind of depth. Maybe conversing with your limitations and querying them is in itself a kind of faith.

The premise of this entire collection, although full of questions and doubt, is that there is a God. The comfort of grief for people who believe in the afterlife is that the afterlife is a better place. That eternity, where a person’s spirit goes to after death, is the place where they can find solace and eternal peace, however the lines, “I am human, with a body, / soul, and spirit. / If in person I suffer pang, / what then shall be / the lot of my spirit?” in the poem “Comfort to My Dead Self” suggests that it is impossible to trust the afterlife when life is full of suffering, who is to say the suffering will not persist in the spirit realm?

As the book progresses, the cry and desperation intensify, as seen in “Pleading for Favor” which is a heartfelt sincere prayer for favour and mercy. In “Whose Fault, Fate or Mine?” the persona wrestles between taking responsibility for the misfortune in their lives or resigning to fate. The imagery of being in a dungeon or prison in “I Surrender It All” conveys the sense of being trapped and in need of rescue. The poem is a prayer of surrender and supplication to God for freedom and deliverance from captivity.

The poem, “Agony of a Hidden Greatness,” is the persona’s lamentation of unfulfilled potential and the pain of waiting for greatness to arrive. “In the Dungeon of Despair” is a cry for help and rescue from the depths of despair and mediocrity. It’s no surprise that “A Letter to My Flesh” is one of the last poems in this collection as it is an introspective and philosophical exploration of the relationship between the persona’s flesh, soul, and spirit, and the struggle to do good and avoid evil.

The beautiful thing about the book is its use of simple language to portray the direst of circumstances and the heaviest of emotions plaguing the human condition. The use of prayer and intercession as a poetic device throughout the book exposes the resonating themes of suffering, hope, faith and redemption. Most poems in this collection masterfully capture the air of despair and lamentation.

If Okonkwo intended to use run-on lines and lengthy stanzas to evoke a sense of endlessness and make tangible for the reader feelings of longing and frustration, then he has succeeded. If not, the poems in this collection can benefit from shorter stanzas and pacing to improve flow and not wear out the readers especially since the air of despair and lamentation in the poem is repetitive. It feels as though the poet is telling us about the same range of emotions without providing specific experiences to anchor them.

Peter Okonkwo’s “A Cry For Mercy’’ is a spiritual handbook, a manual for believing in the divine while still being human and flawed in this wild world. The questions in this book will make you feel seen.