Features

BN Prose: The Voice From the Mesuardo by Feyisayo Anjorin

It is possible to hear the voice anytime and anywhere. A lot of people have spoken about the overpowering power of the voice; but the stories are not stale because of the variety of experiences with the voice.

It is possible to hear the voice anytime and anywhere. A lot of people have spoken about the overpowering power of the voice; but the stories are not stale because of the variety of experiences with the voice.

The ones who obeyed the voice like robots had no stories to tell.

Salako feared the voice like most Gulungulun residents. He had prayed against the voice. Running errands for the voice is like playing Russian roulette; it is possible to be lucky but it is better by far not to hear the voice.

Salako had been a university graduate with a second class upper for four years, yet the state had nothing good for him in the economic sphere; so he had to discard the thought that someone somewhere would help him rise. He had paid the tithe of the little money that had come his way for years, but all the rosy promises of his pastor – which had been his motivation for paying it – seemed like lies.

When he finally got tired of writing application letters, writing aptitude tests and being interviewed by young men and women with supercilious expressions, he decided to start fishing regularly in the rivers in the city; he could get enough fish to sell for a good income.

He would work by the riverside under the hot sun; and he would walk for hours barefoot with a basket full of fish on his head to get his goods to the market.

Salako lived in a shack made of rusted iron roofs, cartons and bamboo, held together by nails and ropes – a shack in a community of shacks, with flies and mosquitoes as close as the next pitiful neighbour.

He had to bath in the dark – at night or before dawn – because the so-called bathroom was an open space between two shacks. To take a dump he would have to bend down beside the smell hill of refuse surrounded by shacks; while taking a dump he would have to shush away stray dogs that would be on the standby, ready to eat his shit. Mosquitoes would settle on him like dew as soon as he bends his ass close to the ground.

It was one hell of a life, but Salako never wished for the voice. He was rich in hope, comforted by the song of the young man whose story is known in Ojuelegba, who is now thanking God for life for what he can’t explain. Salako believed in his dreams.

His favourite girl left him because she became a star after starring in a movie about a love affair between a woman and a humanoid robot. She got many award nominations; she did not win any award, but her pictures and her story appeared on all the popular entertainment sites on the Internet.

The girl had removed every digital link with Salako as soon as it became clear that the romantic humano-robotic story would be a hit.

Salako’s phone – having cracks on its screen and a few buttons missing – had been in use for over five lean years and had to be held together by rubber bands. It was Salako’s link to the world, so he treated it like a sick cherished relative.

He had sent over a hundred CVs, to companies in Nigeria, Ghana, Liberia, Gambia, places along the West African coast where he could work without learning a new language. He was hopeful; he was expecting a life-changing call.

Then one day he got a call from a man at an office where he had applied a few years ago in downtown Monrovia.

“Is that Mr Salako?”

“Yes.”

“Mr Salako Ajani?” the man had pronounced the name like someone with no care for the meaning. Salako would overlook this.

“Yes. Please who is this?” he asked impatiently.

“Fred Botha. You applied at S&Q two years ago. Isn’t it?”

He got a job at The Agency, the largest marketing agency in West Africa, with fist-size space on thousands of websites and a billion subscribers on YouTube.

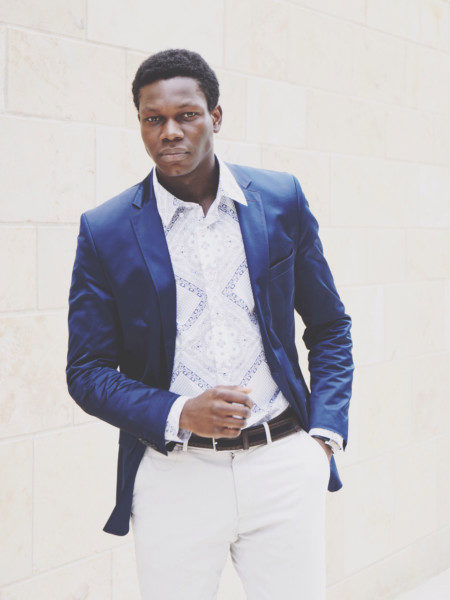

Salako bought a suit for the first time in his life when he got a hundred-thousand-dollars pre-employment bonus. His office was on the top floor of Tolbert Towers, overlooking the ocean at Sinkor. He bought a dozen shoes at the same time and paid for his house near the Executive Mansion.

His poor pitiful past seemed like a hundred years away, and when his transformation became as obvious as daylight the girls who had once seemed beyond his reach because of their sex appeal and expensive accessories began to put more eagerness in their smiles at him.

His first month at work was like a dream. Sitting in his air conditioned office with a beautiful view, sitting with his colleagues in the boardroom, watching his driver stop at the parking lot of his house and hurry to take his bag before driving him to the office, eating tasty meals he never thought he would ever taste; sometimes he would walk to the bathroom and look in the mirror and smile.

He tried to reach out to his ex, the movie star, the one who thought he wasn’t good enough for her new image. He wanted her to know the details of the changes in his life; he wanted her to see him in this new light even if she would not change her mind about what they had.

He dialled her number and waited. He dialled again. One more time. She would know he had been the one trying to reach her. She must have heard the phone ring; she must have seen the missed calls notification on the screen. He dialled the number daily for over a week. She did not reply his emails.

He posted pictures on Facebook: the ones he took in his office, beside the glass window overlooking Sinkor beach; the ones he took at the canteen when he sat between two beautiful and well-dressed colleagues; the ones he took beside his official car; the ones he took by the poolside at the staff club. He kept checking the Facebook notification to see if she would like any of the pictures.

He sent a message to her inbox, he waited. He sent another one; he waited for a month. Nothing from her; even though she kept updating her timeline with pictures she had taken on film sets and red-carpet events. She had a picture with Chris Brown, one with Desmond Elliot, one with Idris Elba; she had one with Wizkid.

Salako thought about this. Could it be that he was not good enough for her even with his new state?

He heard the voice on his way to his office one bright Monday morning as he approached the Gabriel Tucker bridge in his brand new Toyota. He had called his driver earlier that morning to tell him he would drive himself to work.

He had monitored his ex all through the weekend, he had been indoors, eating cold snacks from his fridge and drinking canned drinks.

He heard the voice clearly that Monday morning, like words from lips close to his ears. He parked his car as close to the edge as possible, came down, ignored the curious glances of the cars passing by, climbed the railings of Gabriel Tucker, released himself like a bird, and left the rest to the Mesuardo river.

Photo Credit: Dreamstime