Features

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: Would Fela Have Welcomed French President Macron to his Shrine?

The only way to meet the President of France as a Nigerian is to be a high-ranking politician or be very rich or famous.

The only way to meet the President of France as a Nigerian is to be a high-ranking politician or be very rich or famous.

If none of these describes you, then you’d have had to make do with being one of a few hundred people to have received an invitation to the New Afrikan Shrine this past Tuesday 3 July.

So when the bearded R&B man turned actor Banky W, as host, said we should sit anywhere as there is no VIP section in the shrine, he was half-lying. In a sense we were all VIPs. But even so the seats closest to the stage were for the real VIPs: Macron and Governor Ambode. To prove their own importance, the men showed up several hours after the whole thing was to start.

I had arrived after an expensive and creative way of finding the Shrine: involving paying several bike-men to subvert the bumper-to-bumper traffic imposed on us all by these powerful men. I say find because none of the usual signposts leading to the shrine were present: No one asking me to buy “SK”; no smell of weed as compass; no suya sellers; no petty traders on the day they could make really high sales. Instead I was asked, very nicely, for my invitation. I whipped out my phone, more out of shock at meeting a polite policeman than anything else. But of course, it wasn’t really me he was being polite to. He was working with the idea that a person who could get an invitation to meet Macron was probably important. I laugh.

Now inside, the wait had begun. Banky continued with some filler nonsense about the “special relationship between Africa and France”. Does he even know what he’s saying? I wondered. The geographical incompatibility—the usual gibber that equates a European country to the entirety of the black continent. He was smiling his music video smile, unaware he was putting an exploiting country in the position of benign patron. But of course no one ever accused Banky of political consciousness. A video of platitudes for Macron from Trace TV succeeded Banky’s speech.

“As promised the president of the French republic is here,” Banky said around 9.45pm.

Macron met the artists Victor Ehikhamenor, Ndidi Emefiele Abraham Oghobase. Even as a Frenchman the combination of cameras and jostling meant art appreciation could take a hike, so the president made approving noises. In company of the Lagos governor, Macron then moved to the VIP section. Already we were informed that some persons already seated close to the stage had to leave. No VIP sections, eh?

The dance group Footprints of David performed a welcome number in Yoruba. Sitting with the governor in front, Macron wore no jacket on his long sleeved shirt; Ambode wore a t-shirt. Speech here, speech there, speech everywhere. It seemed strange that a Nigerian city was welcoming a foreign president with loads of talk and no pounded yam.

“We are glad to have you in our midst,” Ambode said as Fela rolled in his grave at the idea of politicians taking over his son’s podium. A brief tour of the shrine became a tour of Macron’s face on other people’s phone screens. All of these important people became animated at the idea of a small, slim white man smiling into their phones. This welcome proved enough to empower the night’s guest to make pronouncements on Fela. “He was a politician because he wanted to change society,” said Macron.

He later said something more in the spirit of Fela: “What happens in the shrine remains in the shrine.” Apparently back in 2002 as a French embassy intern, Macron had visited the Shrine. He’s a cool expat kid then, pretty sure he was offered a few intoxicants.

“I do believe we have to change,” he said in response to a different question from the accented Keturah King. “We have to build a new common narrative…this place is important for African culture.”

Macron of course belongs to a generation of Europeans, of white people from South Africa to Australia, who want to shrug off the impact of the past while enjoying the riches that past has given their present. “My generation never experienced colonisation,” he said, adding that, “We have to move forward“. This of course is a no brainer. But, as someone said, “the past is never dead; it’s not even past.”

Today Paris is dotted with pretty produce made from the past and immigrants are asked not to seek it? As he went on, Macron’s smiling anti-immigrant stance turned up. Africans, he said, “have to build their future here in Africa and we have to assist them.” He then announced that there would be a culture season in France for Africans and by Africans. “We need new people to make a [new] narrative.”

So Macron came to ensure Africans stay put in Africa, while France gets a chance to see the best of African culture. Good girls might go to heaven; but the rich and famous go to Paris. The poor can inherit Africa.

Yemi Alade came on around 10.40pm with a medley featuring ‘Ferrari’, ‘Kissing’ and other bland Yemi Alade songs. Selected because of her deliberate courting of French Africa, Ms Alade split her music between both languages of her oeuvre. But her performance didn’t quite fit the atmosphere. Cameroon’s Charlotte Dipanda followed. Neither performer quite drew the attention of the Shrine. In fact, it seemed only the presence of the governor or the small white guy from France could do that—evidence of the inappropriateness of the selected singers, but also a tribute to Nigeria’s eternal worship of whiteness and power.

At some point in the night, Kunle Afolayan got Macron to do some acting surrounded by Nollywood royalty—Jide Kosoko, Ramsey Nouah, Rita Dominic, Omotola Jalade among them. “He doesn’t know,” whispered a friend of mine. “He will see himself in a film or two.” I chuckled. If it would take Macron to bring back the Afolayan that made Figurine and October 1 then the director’s sheepish smile onstage was permissible, but watching the gaudy mess onstage, I had a sinking feeling that Afolayan’s era of quality filmmaking might be over.

Mo Abudu, another believer in gaudy mess as cinema, asked Macron a few questions. To one question, Macron said he was available to act in Nollywood. Ms Abudu, in heels towering over the man, then asked how a Nollywood film could go to Cannes and win the Palme d’Or. I snorted. It seemed the kind of question the producer of such a film as Fifty would ask. Her real question was how can shallow good-looking films like mine win the prestige on offer at Cannes? The real answer is they can’t. But Macron, ever the diplomat, said, “I’m not the one to answer this question. Abderrahmane Sissako is the one to answer it.” The man who made Timbuktu came out on Macron’s prodding and gave a noncommittal answer. “Work hard and be patient,” he said. Ms Abudu clearly wanted an annotated roadmap to Cannes glory. No such luck.

Near midnight, the place was near empty as Ara the drummer performed, dancing her red hair for Macron’s pink face. Ambode, with no hair, whispered something in Emmanuel-with-the-good-hair’s ear. Ara approached and handed the Frenchman a gift. Youssou N’dour and Angelique Kidjo would be drawn to say a thing later. “Are you still alive?” asked Kidjo. “I don’t know about you but I’m tired.” She spoke for all of us.

Banky, who was still alive, launched into superlatives to bring on Femi Kuti. As always the eldest Fela son was manic on the keyboard. The dancing girls in green and orange ass-shaking gear appeared in their cages. Macron, whose country has “liberté” as first word of its motto, didn’t seem to notice their appearance.

A part of Femi’s song had the line “dem just dey lie”. If it was a line directed at politicians, he had two of looking him in the eye. But, of course, if Fela’s activism was reckless, Femi Kuti’s has been relatively risk-free. This endorsement of politicians was the next step. Some might even say it was inevitable. I asked a Fela scholar friend if my thoughts were uncharitable. Would Fela have gone this route?

“Macron wouldn’t have gone near the Shrine were Fela to be alive,” said Kayode Faniyi, confirming my suspicion. “That’s assuming Fela didn’t ‘sell out’ in his later years, ease into a national icon of the sort endorsed by government. And given Macron’s paternalistic comments about Africa last year, ‘Beasts of No Nation’ might be on full blast. And really, Macron’s politics in France has so far been problematic, so yeah, it wouldn’t have been a nice reception.”

Femi Kuti bowed elaborately and thanked the governor. “He feels the pain of Africa,” he said about Macron, whose view on immigration seemed to have found a willing mouthpiece in Femi who said it was possible to have Africans stay here. Thankfully, he stopped talking and went back to playing music. He pulled Macron up and started shouting his lyrics in the white man’s face. The tired, non-dancing president reluctantly began clapping.

The event was at its end as Asa, Youssou N’Dour and Angelique Kidjo stepped up to dance too. These were the real VIPs of musicians, each with a seat around the politicians. And it seemed rather fair that for all of her fame, Yemi Alade was not nearby.

Watching the scene, I thought this was a fine gathering of great African musicians. But why had it taken a white man in Africa to bring all of them together?

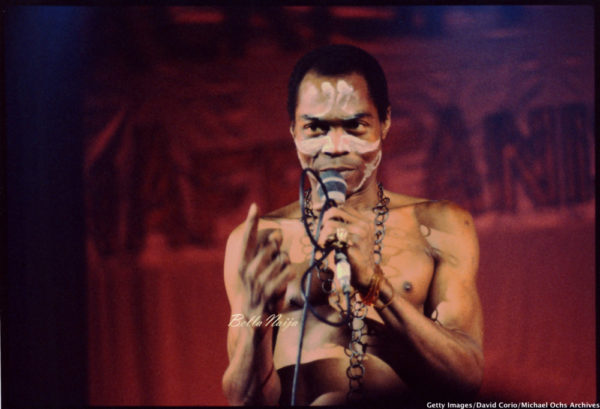

Photo Credit: David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images