Features

Udochi Mbalewe-Alabi: Girls in The Gambia Want the Right to Control Their Bodies

Two days before my traditional wedding, I stood in the kitchen of my apartment in Lagos with my mum, ticking off items on the wedding list dad had brought from his village visit. Faint beats of Davido‘s “Unavailable” drifted gingerly into the kitchen, a spillover from the birthday party happening downstairs.

Our neighbors were throwing a party for their one-year-old, and the whole place buzzed with life. In Lagos, these parties were a constant source of joy, a welcome disruption from the usual hustle and grind. Usually, everyone in the compound was unofficially invited unless you’d had a recent fight with the host. It was an unspoken agreement. The closer you were to the host, the more you “owned” the party. In fact, if you felt close enough, you could extend invitations to your friends. And when they ask whose party it is, you’d casually say, “Oh, it’s my neighbours’, but it doesn’t matter.” While going out to join the party wasn’t on our agenda, the music’s infectious beats had a way of sneaking into our apartment. Here, in the privacy of our own space, we would let loose, dancing in ways we wouldn’t dare in public. Even when the noise threatened to burst our eardrums, we knew a plate of steaming jollof rice and chicken, a communal appeasement for the noise, would soon arrive at our doorstep accompanied by cans of coke and malt. This, after all, was Lagos in its essence – a city of captivating opposites, where salsa nights on Tuesdays coexist with strip clubs and church vigils’ on Fridays. It could make you laugh out loud even as it tested your tolerance and somehow squeezed joy out of every honk, shout, and beat.

Amidst the celebratory chaos, my mum, usually composed and stoic, suddenly started speaking in a voice barely above a whisper. We weren’t a family known for emotional displays, so I cast a questioning glance her way, a cynical ‘Is everything alright?’ hovering in the air. This conversation, however, would feel different. It would become the first, and perhaps, only time we truly shared our vulnerabilities as mother and daughter. As if sensing an opening, she started talking about her life. A life where she wasn’t the strong woman I admired, but a girl who had things done to her, things she had no say in. Sex, she confessed, wasn’t something she ever enjoyed, but one of forced pleasure, and faking moans to avoid whispers and judgment. She spoke about how she was handed over to a man, barely out of teenagehood by her own family. Then, the word slipped out from her lips: circumcision, a word that felt too clean for what it really was. She had had what they call complete removal. Her brothers, even her parents, saw her coming of age and decided they needed to ‘fix’ her. She pulled down her skirt, unwrapped her undergarments, and showed me a faint scar. A thin line that looked like a young plantain tree they’d chopped down before it ever had a chance to grow. Anger bubbled up inside me, hot and simmering, not just at my uncles and grandparents, but at these traditions that boxed us in, told us we couldn’t control our bodies, and dictated our lives before we even had a chance to live them.

Like the thick Lagos humidity, the weight of my mother’s words settled upon me that evening. Sleep, which had been a recent companion, deserted me. I stood up to shut the window from the deeply infuriating sound of our slightly overused generator, yet, I tossed and turned, praying for sleep, and hating my insomnia for rearing his head after a long time of its dreadful absence. You see, I suffer from what some might call ‘occasional insomnia,’ and my last bout was when Uncle Deyide, my Dad’s cousin and an upcoming musician, had trended on Twitter for two days for clapping back against an acclaimed African Afrobeats star, who had a cult-like of followers.

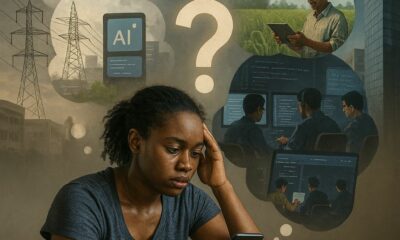

Feeling frustrated, I picked up my phone just to distract and lull me to sleep, but instead, it sent me down a rabbit hole of information on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). It was during this exploration that I stumbled upon the news of The Gambia potentially repealing the FGM ban. Immediately, I dialled Abdullah’s familiar number, my Gambian friend from the African exchange program I participated in two years ago. Abdullah, with whom I’d shared many conversations about our home countries, seemed the perfect person to talk to.

‘Hi, Abdullah,’ I stammered, voice tight with worry. ‘Did you hear about… The Gambia?’

‘Hear about what?’ Abdullah’s voice came through the line, laced with concern.

‘The law!’ I blurted. ‘The one that stopped… erm…They might get rid of it!’

‘The FGM ban?’ He quipped, unsure if it was what I meant.

‘Are they really thinking of getting rid of it?’ I asked.

Relief washed over him, ‘Finally! Someone to talk to about this. Yeah, it’s true. Crazy, right?’

We talked for a while, and then Abdullah paused, then continued, ‘Listen, this reminds me of something…something that happened to my sister, Isatou. Remember Isatou?’ he asked.

‘Yes, yes. Your beautiful elder sister,’ I replied.

‘I was just a kid, maybe six or seven,’ he began. ‘Two strange women and a man showed up at our house. They took my mother outside, and when she came back, she was carrying this brown bag – it looked like trouble even to my little eyes. They told me to get my teenage sister, Isatou, and then shooed me outside to play. I was happy for a break and a chance to play outside. I had been inside arranging the clothes my mother wanted to send to Auntie Fufa the next day, I didn’t even notice the fear mum was trying to hide.’

‘What happened then?’ I whispered, already dreading the answer.

‘Then I heard screaming, Isatou’s screams and mum’s muffled sobs. I didn’t understand, but fear made me want to run inside. I tried to, but the man grabbed me rough, shushing me away. He was at the door while the two women were inside. So I cried, sitting helplessly by the closed window. A while later, the first woman came out, disheveled but strangely happy, like she’d done something good. Her skirt, a flowery yellow Ankara, had bloodstains and was seated one-sided and unevenly on her waist. The man guarding the door was gone, so I snuck in. Isatou was lying on the floor, with blood all around her. She looked pale like she had been running for three days nonstop. I shivered. She called my name, her voice weak and pained. I looked at mum, but she was busy talking to the other woman. Even when I called her, she wouldn’t look or answer me. It was like that for a whole week. One minute talking to herself, the next praying silently. Later, I learned she felt guilty, torn between protecting her fiercely-beloved Isatou and this… tradition.’

‘After that day, a piece of Isatou seemed to vanish. Her playful spirit, her teasing laughter that built gradually before cascading down her throat, faded away. Occasionally, glimpses of the old Isatou would resurface when she played with our youngest sister, Binta, but it would flicker and disappear just as quickly. Sometimes, she’d appear lost in a world of her own. Other times, the smallest thing could trigger an outburst, her anger boiling over like a forgotten pot on the stove. We learned to tread carefully around her, never quite knowing which Isatou we’d encounter – the simmering one, the withdrawn one, or the one on the edge. Even a simple request like ‘Isatou, can you help…’ felt like a gamble. We’d either approach a request with cautious optimism, hoping for the gentle Isatou or brace ourselves for a flare-up.’

Abdullah’s voice hitched slightly, heavy with emotion. ‘It was impossible to predict,’ he said softly. ‘You never knew how she’d react. Slowly, over months, Isatou began to piece herself back together. It wasn’t the same, but we cherished and held those glimpses fiercely. When she decided to get married, a bittersweet relief washed over us. Later, my sister would confide in me the horror of her experience, and the betrayal she felt towards our mother who stood by and watched. She described the helplessness, the searing pain, and the way they used hot water to cleanse the wound. It was a constant message that her worth was tied to childbearing, not her pleasure. Being female, she realised, seemed to come with a lifetime of pain.’

‘Two years later, during one of Isatou’s visits, I overheard a conversation. Tears streamed down my mother’s face as Isatou confessed, ‘I can’t… I can’t have intimacy. It is always painful, always, and I am finding it difficult to conceive. My husband is angry; I am angry. We can’t consummate the marriage properly because… Her voice broke, replaced by a sob.’

‘I saw shame flicker in my mother’s eyes,’ Abdullah continued, ‘I was quite shocked to hear my mother admit that she and my father had made a terrible mistake in letting Isatou get cut.’

A cold dread settled in my stomach. This was more than just Isatou’s story. It could have been mine too. I stood up pacing the room frantically. Abdullah continued to explain how the bill to reverse the ban on FGM enacted in 2015 had not only passed the first and second readings but was now at the committee level! How could 42 out of 46 legislators, sworn to uphold and protect the rights of its citizens, judge that this ban was unnecessary and so had to be repelled? Was it blind adherence to tradition or due to a deeply-seated, overriding belief that pushes one against all features of sense and sensibilities as well as our collective human empathy, even if it caused harm? Or was it something more sinister? I had so many questions inside me.

As I began to think deeply about it, it dawned on me that this exposes a deeper issue: the power imbalance between men and women. Men like Almameh Gibba, the bill’s sponsor, wielded the twin blades of culture and religion to control women’s bodies, dictate women’s experiences, and reduce them to mere vessels of tradition while hiding behind that veil to argue that the ban violated cultural and religious rights. Whose rights were they prioritising? I wondered. The right to inflict a lifetime of physical and emotional pain on girls, all under the guise of tradition? This very tradition that had shattered countless lives, like that of Jaha Dukureh, the UN Women Ambassador for Africa, who was forced into marriage as a child, and had to travel alone from Gambia to New York City as a young girl to be with a complete stranger. Only later did she find out that she had undergone type 3 FGM, the most severe form as a baby, leaving her with lasting physical and emotional scars. Years later, these scars prevented her marriage from being consummated and forced her to endure yet another painful surgery.

Is this what tradition looks like? Can a tradition that inflicts pain truly be considered progress?

This, I realised, was the essence of power: The ability to change, to shape reality. To name. To be. To do. To be ill-concerned with the critical nature of oneself while being protected from intrusion by the other. Yet in this situation, power creates brutal extremes: powerful versus powerless, predator versus prey, rich versus poor, strong versus weak. There was no middle ground, no blissful neutrality. There is only context, and context shape power. In Nigeria, just like many other African countries, power structures were deeply flawed, and tipped heavily in men’s favour. The lack of strong female representation in these structures only amplifies this problem. So, we are left with no choice but to fight for representation and power to control our own destinies.

My mind raced with frustration and I started to imagine some analogy to describe this situation to Abdullah. It was like a bull – arrogant and oblivious – demanding a lizard change its red scales to fit its colour choice. The lizard, fearing rejection, obeys, only to be left forever wounded. This absurdity mirrored those who controlled women’s bodies while ignoring their well-being. My legs began to shake like they do when I get intensely worried. I shrug it off and continue to explain to Abdullah. Understanding, I told him, was the key to dismantling this oppressive system. Were the women who supported FGM brainwashed pawns in a game of tradition? Or was it something more nuanced? Perhaps these women genuinely believed FGM was necessary or that it offered them a sliver of control in a world dominated by men. Perhaps they feared societal rejection if they spoke out. I desperately needed to understand their perspective. Dismissing them as brainwashed wouldn’t solve anything.

‘Even in the aftermath of the 2015 FGM ban, enforcement was nonexistent. Despite the law stating that knowing about FGM without reporting was a crime, and practicing or supporting it was an offence, people continued the practice, either discreetly moving from the cities to the villages or by crossing borders to neighbouring countries. The numbers spoke for themselves: less than five arrests since the ban, while FGM remained rampant,’ Abdullah elaborated.

The situation in The Gambia frustrated me more. This peaceful and welcoming country, a stark contrast to Lagos’ vibrant chaos, had banned FGM. Disappointment gnawed at me. I confided in Olaedo, my activist friend, a woman who had faced threats and attacks on her home yet refused to back down from fighting for women’s rights. She mirrored my frustration perfectly. ‘They preach about tradition,’ she scoffed, ‘but have they ever felt that cold blade on their body?’

In Nigeria, women’s voices are but a whisper in government. With only 3 out of 109 Senators and 17 out of 360 Representatives in the 10th Assembly being women, the lack of female representation is stark. The Gambia wasn’t much better, with just 6 female legislators out of 58. How could men, with no personal experience of the practice, understand the devastating impact of FGM? Olaedo shared a personal story to illustrate the point, ‘A friend of mine, Hadizah, went through FGM as a young girl. Years later, she confided in me about the constant pain, the difficulties she faced during childbirth, and the emotional toll it took on her.”

Sadly, Hadizah’s story isn’t unique.’ Olaedo continued, citing statistics from the WHO. FGM could cause severe bleeding, urinary problems, and later cysts, infections, complications in childbirth, and an increased risk of newborn deaths. In the most extreme cases, it could lead to shock and death. This reality clashes harshly with the tireless work of women’s organisations. Years of constant fundraising appeals has created donor fatigue and skepticism about fundraising’s effectiveness and the authenticity of some activism, and progress feels stagnant. Abdullah’s story of his sister, Setatu, who could finally conceive only after expensive fertility treatments, is another stark reminder of the consequences of FGM. The fight against FGM is a marathon, not a sprint. If this ban is overturned, it sets a dangerous precedent, even across other African countries. Some people might see the repeal as God’s will, and further entrench the practice. ‘This isn’t over,’ Olaedo stated, her voice regaining its steely resolve. ‘We can’t let them win. We need to speak out, educate our communities, and show them the true cost of this tradition.’ I nodded, a newfound determination sparkling in my eyes. For the first time, I truly understood. This wasn’t just about a ban; it was about a girl’s right to choose, to live a life free from pain and fear. The fight against FGM had just begun, and I am fully ready to join.

***