Features

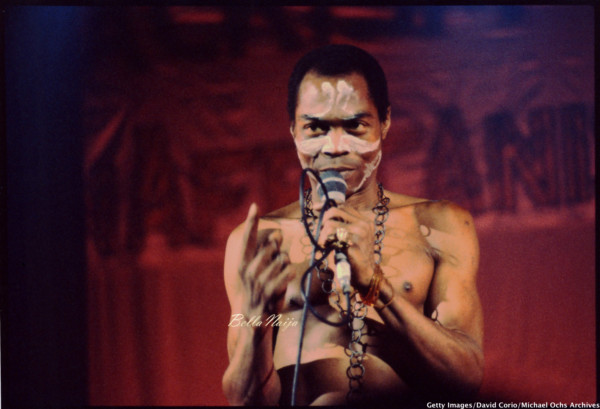

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: Seeing the Many Sides of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti

Sitting in the dark with mostly white faces listening to Fela can be a bit uncomfortable—especially when the song playing alludes to slavery. “Why black man no get money today?” Fela asks, and then explains that the black man was minding his business before a group of white persons showed up. “Na since then trouble start.”

Sitting in the dark with mostly white faces listening to Fela can be a bit uncomfortable—especially when the song playing alludes to slavery. “Why black man no get money today?” Fela asks, and then explains that the black man was minding his business before a group of white persons showed up. “Na since then trouble start.”

Because it is sung in pidgin, the song is a bit coded from non-Nigerian audiences. But Joel Zito Araujo, director of the new documentary My Friend Fela, uses subtitles, which should make it easy for a white audience to decipher.

As a Nigerian, it seemed incongruous that a Fela documentary should start with a criticism of white people when a chunk of the songs my father and I have played are targeted at people with the same skin color as Fela’s. But, of course, Fela is no longer just owned by Nigerians. The genie has left the lamp. And, as it becomes clear, Araujo is heavily invested in representing Fela as an external member of the Civil Rights Movement. In other words, the mostly white festival-goers at the International Film Festival Rotterdam are what the doctor recommended for this documentary film’s premiere.

In this way, My Friend Fela is similar to its predecessor, Alex Gibney’s Finding Fela, in how they both have a Nigerian audience as something of an afterthought. This might make you want to question how it is that only foreign filmmakers have realized the cinematic treasure trove that is Fela’s life. Perhaps this is about the funding? Or is it about realizing such a work has no real hope of screening without trouble from our government? In any case, Araujo did face some difficulty: he was refused a visa and it was the intervention of Wole Soyinka who finally got him and the writer Carlos Moore into the country. But their crew members were denied visas.

The documentary is mediated through Carlos Moore, the author of the popular Fela biography This Bitch of a Life. He speaks to different persons about Fela—including his son Seun Anikulapo-Kuti but not Femi Anikulapo-Kuti, one dancer-cum wife, his singer-cum lover Sandra Isidore, and two cover designers—and they all agree that the man was special. What they don’t really say, except toward the end, is the man also had his issues. The film is more a celebration of his music genius—there is a very good scene where an interviewee gives a musical basis for the widespread acceptance of his music and adds that it helped that Fela’s English was “straight and strong.” His lamentable actions receive little onscreen time.

One of these actions involves one of his 27 wives, who appears to have been taken in by Fela when she was a minor. At first she was scared, but she summoned the courage to go to his Kalakuta home. When she arrived Fela praised her beauty, and although the documentary never explicitly states what they got up to, by her own admission she was about 15 when she started to live with Fela.

Even the least woke person would be tempted to use the word predator to describe the man. This part of the documentary quickly ends, receiving no real commentary or criticism from Moore as interlocutor. It is almost as if Araujo is goading us to make of it what we will. Around me, I could feel the audience in the Netherlands squirm—the Me Too movement is sweeping the globe, after all.

But nobody brought up the scene during the Q&A following the screening, although someone asked what Fela’s mother—a feminist before the word became faddish in Nigeria—thought about her son’s treatment of women. It is a question that can no longer be answered. The director did say Fela’s relationship with women was complex.

I am not sure if this was supposed to be unique, because it isn’t. Most men treat female romantic or sexual partners different from how they treat women in their family. This issue might be related to sex—in both meanings of the word. It is easier to get a man to offer equality if sex or its possibility is removed. So you have Fela—raised by a feminist and converted into politics by a woman—having ideas incompatible with feminism. A performance where Fela holds the head of one of his dancers and playfully/forcefully has her dance made me cringe.

By the film’s account, the most important event in Fela’s life was his mother’s defenestration by Nigeria’s army. In the documentary, you see him change physically after this incident: his complexion darkens and his face can’t quite rid itself of subdued anguish. His son Seun says the attack was probably more on the Ransome-Kuti matriarch, who supported Chairman Mao and was anti-capitalist, but Fela never really recovered from the attack.

It was around this time he began to flirt with the mystical and seemed to fully develop a dictatorial approach in his affairs, so much that by the time of his death, in 1997, Fela had alienated some of his associates. Thankfully, My Friend Fela recognizes that the life of Fela was tragic—he’s beaten, he’s jailed, his mum dies, his friends leave, his son Femi is unhappy, he contracts AIDS—but very important parts of it were celebratory. Fela’s life is almost like his music: part sad lyrics, part irresistible groove.