Features

How Should We Tell The African Story? – A Conversation with Fisayo Soyombo

This is what it means to be authors of our own stories: not writing single stories about Africa(ns); letting go of stereotypical views; not focusing on just the negatives and neglecting the stories of Africans ‘killing it’ in every industry.

Editor’s note:

As we deliberated on whom to invite for the storytelling series, we thought of Fisayo Soyombo. Our lead said, “Fisayo is giving voice to the voiceless.” And that is true. Part of telling good African stories is amplifying voices that would have otherwise been stifled, and bringing issues, that would have been buried and forgotten, to the fore. More important than telling African stories is how we tell them. From a journalistic point of view, Fisayo Soyombo tells us how we can tell holistic and distinct stories of Africa and its people, which includes not whitewashing the continent and equally not focusing on the negatives of the continent or reporting about our woes with glee.

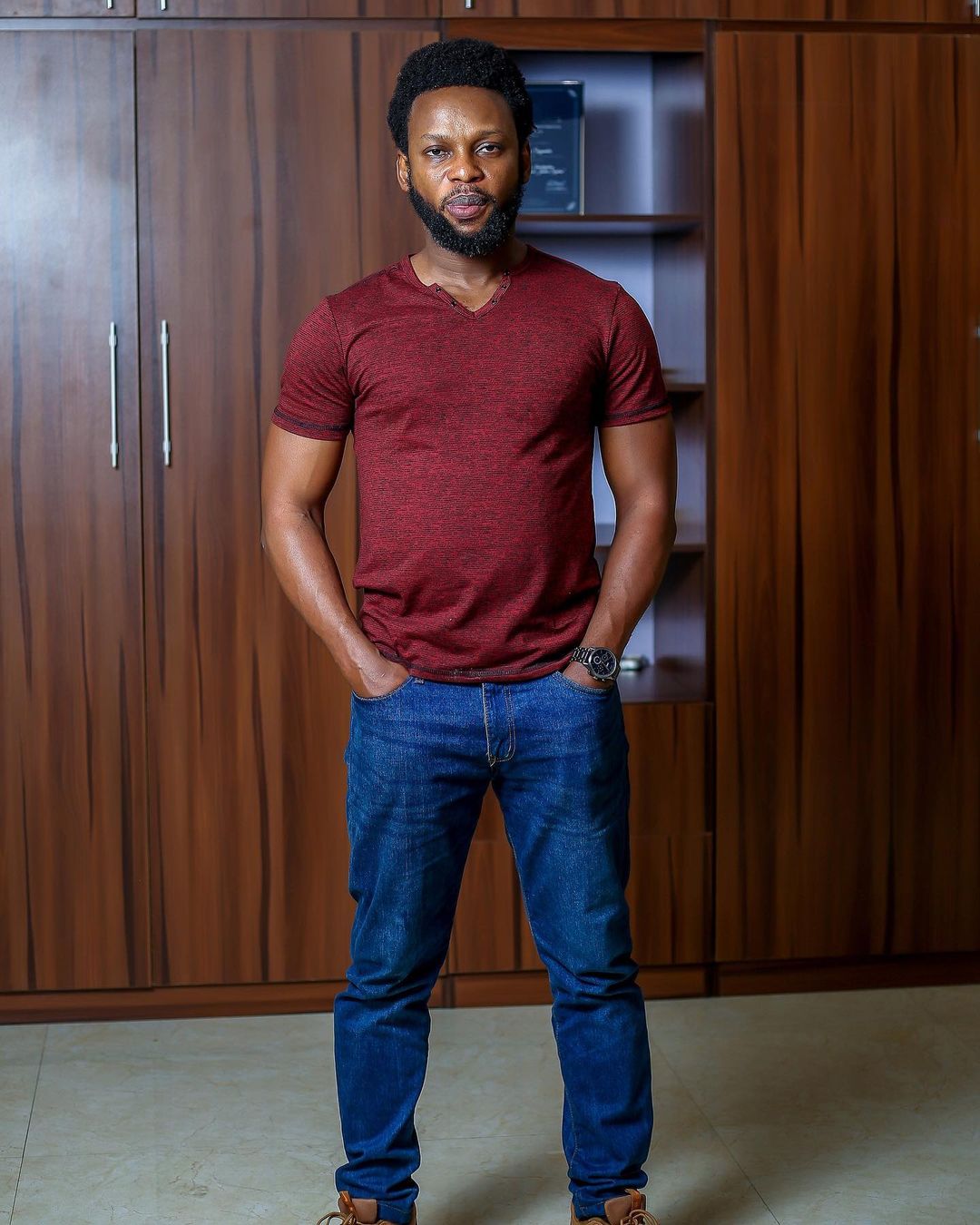

Fisayo Soyombo did not set out to be an investigative journalist; 2 weeks of reflection brought him here. He was in 100 level, studying animal science at the University of Ibadan, but deeply involved in campus journalism. He realised he was passionate about writing and journalism, so why not do that instead? “I had 2 weeks of reflection, asking myself which I would go for between journalism and animal science.” By the end of his 100 level, he moved to study journalism. “I told myself I would do journalism for impact – as a tool to better the society. Journalism with results.”

In 2005, Fisayo started working as a reporter at The Guardian, but he had an intense need to make impact. Years into the industry, he realised that to make his dream of making an impact in the society come through, his kind of journalism had to be investigative. “Basically, I evolved into investigative journalism,” he says.

In 2018, while still working with TheCable Newspaper, Fisayo Soyombo went undercover to report on “the porousness of Nigeria’s highway policing” by driving the equivalent of a stolen vehicle from Abuja to Lagos for 28hours 17minutes without being arrested by bribe-collecting policemen in 86 checkpoints.

In 2019, Fisayo Soyombo spent five days in a police cell and eight days as an inmate in Ikoyi Prison to track corruption in Nigeria’s criminal justice system, beginning from the moment of arrest by the police to the point of release by the prison. His three-part story detailed his time spent undercover in jail at a Lagos police station, and as an inmate in Ikoyi prison.

In January 2020, Fisayo spent 3 weeks, including 10 days on admission, as a(n undercover) patient of Yaba Psychiatric Hospital. His findings, published in Business Day Newspaper, included “the decrepit state of hospital facilities, gross shortage of critical staff despite a bloated workforce widely believed to be populated by ghost workers, low quality of service delivery, arbitrary charges on patients, and so on.”

In 2021, Fisayo founded the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), an independent, not-for-profit organisation that combats injustice, holds power to account, and tells stories of the wronged in the country, as well as stories of Nigerians doing amazing things around the world. Fisayo says of FIJ: “If I drop dead today, FIJ won’t die, because there are people who have seen the contribution it is making to social justice and won’t let it die.”

Many times, when people say “we have to tell original African stories” or “change the narrative of Africa”, it is immediately translated to sweeping certain stories beneath the carpet, portraying black people as kings and queens, or over-glamorising the cultures and traditions of the people. For many journalists, the act of unearthing decadence can then seem like disloyalty to one’s country and continent, or seem like the country and its people are being portrayed in a bad light. Fisayo doesn’t agree with that.

“You can tell a negative story with glee,” he says, “you revel in such stories. But you can also tell that story in a manner that shows it’s about passion for a better society. And I believe that people can read in-between the lines.

It’s not about painting the image of the country in a certain way. If you have a sinking and decaying structure, you can paint it, but that doesn’t stop it from sinking. It’s better we know what the problems are and try to fix them.

In my non-investigative writing, I report positive stories a lot of times. At FIJ, when people do positive things, we publish them because we are proud of them. That’s what balance means in our job. Showing that there are people who are doing us proud. But also showing that there are aspects that need to be better.”

Telling African stories as journalists, Fisayo says, is about us creating balance in our reportage. Being honest with ourselves enough not to sweep our ills under the carpet, especially the kind of ills that need exposing to be nipped in the bud. And equally being positive enough to celebrate our every win – something “we don’t do quite enough, to be honest.”

“A journalist’s job is to write things the way they are,” Fisayo says. It’s not the journalist’s prerogative to seek a better perception for Africa; that’s the job of our leaders and their PR specialists. The more we’re able to raise the quality of leadership, the easier it is for journalists to cover the continent in good light. Journalists cannot resort to whitewashing the most disturbing aspects of our continental life just for the sake of positive imagery. It is their job to speak truth to power and hold governments to account. When such efforts yield results, the African narrative becomes naturally improved. The lasting solution is to build a better Africa.

It is equally important for journalists, in particular, to not become fixated on the negative as to sideline or even completely ignore the positive. Report the corruption in Nigeria’s sports sector, by all means, but also write about that breakout Nigerian kid excelling above his peers in one of the harshest leagues in Europe. Write about ASUU strike and Nigeria’s comatose education sector, but also write about the Nigerians topping their classes in some of the world’s best universities.”

Aye!

Fisayo Soyombo is doing something very important: writing for impact. But in a country like this where revealing the declension in a sector does not automatically mean justice, investigative journalism can become a vapid profession. Fisayo is unfazed. He says he is “living a course that is beyond me.”

“There was a story I did in 2016 about forgotten soldiers who got injured fighting Boko Haram and were abandoned by the army and the government. After I did the story, the lead soldier I featured, who had been begging the army for a prosthesis for 44 months, got a prosthesis. It’s the most impactful story I’ve done, and it brought me so much joy.

Every single day that I wake up, I know that my life is benefitting someone. I am living a life for a course that is beyond me. I don’t empower someone else with the opportunity to stop me directly or indirectly. I take the decision out of the hands of other people and concentrate it in mine. When I stop reporting these stories because the system (or those meant to do the work of getting justice) has failed to do its work, then I have given them the power to stop me. I don’t want outside forces to have such a grip over me.”

‘Outside forces’ could be more than people. It could mean being thrown into jail at the very least or being murdered. Fisayo Soyombo is all too familiar with threats and arrests, having been arrested for one of his investigative works in 2021. He has also come to terms with his mortality. During the interview, he talked about death over and over again such that you’ll know it has no grip over him.

“I have a philosophical approach to life, I see life as a gift. The life I have is not for me; it’s a gift from God and God has the right to withdraw that gift. It’s not my job to cage that gift because I don’t want to be injured or I don’t want to die. I’ve come to terms with my mortality. I am not scared of death; I like to demystify death. I realised long ago that I have no absolute control over how long I live, so I decided to take absolute control of how I live my life.”

Fisayo is an investigative journalist with grit, perseverance, and doggedness. He has always been like this, even as a child. “I found things that were hidden at home, and touched things that were forbidden. My father would look at me and say ‘aya ko e’ (you’ve got audacity)”. Fisayo got his fearlessness and perseverance from his mother, and his will to always do the right things from his father.

But doing the right thing, as a journalist, can be dispiriting in our society where journalists are persecuted for revealing things that were intended to be hidden. In a society where storytellers and journalists have very little to no funding, yet are saddled with the responsibility of championing social change and changing the narrative of the continent. How do we drive the need to do journalism the right, non-brown envelope way? Fisayo doesn’t believe a lack of funding is an excuse for corrupt or biased journalism.

“The first step is to do quality journalism. Journalists have to realise that incorruptibility and excellence are two different concepts; one without the other protends huge consequences for the survival of any media career. An incorruptible but average journalist is unlikely to receive significant support for their work; it has to be a blend of doing great journalism while preserving one’s conscience. I still believe in the good, old maxim: ‘good journalism sells’.”

Telling African stories isn’t for storytellers or journalists or filmmakers alone. One way or another, we all tell the African story. You tell your stories when you amplify certain voices, share certain tweets, and make certain content go viral. Fisayo says you should “mind the platform”.

“Get credible sources. I fact-check even videos. It’s common to see people circulate videos from 5 years ago and make them look like they’re recent. Before resharing videos or content generally, ask yourself: have I personally verified that this is true? If you’re reading from an online platform, check the credibility of the platform and its owner. Check their track records – are they the kind of platform that will mistakenly share false information and then come back to retract their statements or correct their mistakes when they have the new and correct information? Watch out for even individuals who claim to be activists.

Politicians go to any length to whitewash their image, so it’s equally important for people to be circumspect. After what happened at Lekki during the #EndSARS protests, a firm, through an agency, requested an investigative journalist who would go round the scene, see and write something that will be pro-government. They wanted an investigative journalist to do a piece so they can say “after much investigation, it was discovered that people were not shot, people did not die.” Apparently, they did their findings on me and never got in touch.”

Beyond that, we all must be conscious of the kind of stories we give attention to or the content we gleefully and willfully share. When you skip stories of Africans doing great things around the world and instead tweet and retweet only negative stories about the continent and people, you are equally piping a certain stereotype of the continent. “Keep engaging with good content. Pursuing justice is not just about writing, the public should also engage with the stories. Their engagement is a big part of getting social justice,” Fisayo says.

Fisayo is planning to work on another investigative piece next year, but hey, we’re not letting this cat out of the bag. Beyond the need to make an impact with his investigative pieces, Fisayo strongly believes that as Africans, we must tell our stories or else others would tell them for us and we can’t get angry over whatever angle they chose to come from. He also believes that whether or not these stories put the continent in a bad light, they must be told. There’s a caveat to it though: it has to come from a place of giving voice to the voiceless, and not a place of elation over the predicament or state of the continent.

This is what it means to be tellers of our own stories: not writing single stories about Africa(ns); letting go of stereotypical views; not focusing on just the negatives and neglecting the stories of Africans killing it in every industry; not pandering to the western world to make your story profitable.