Features

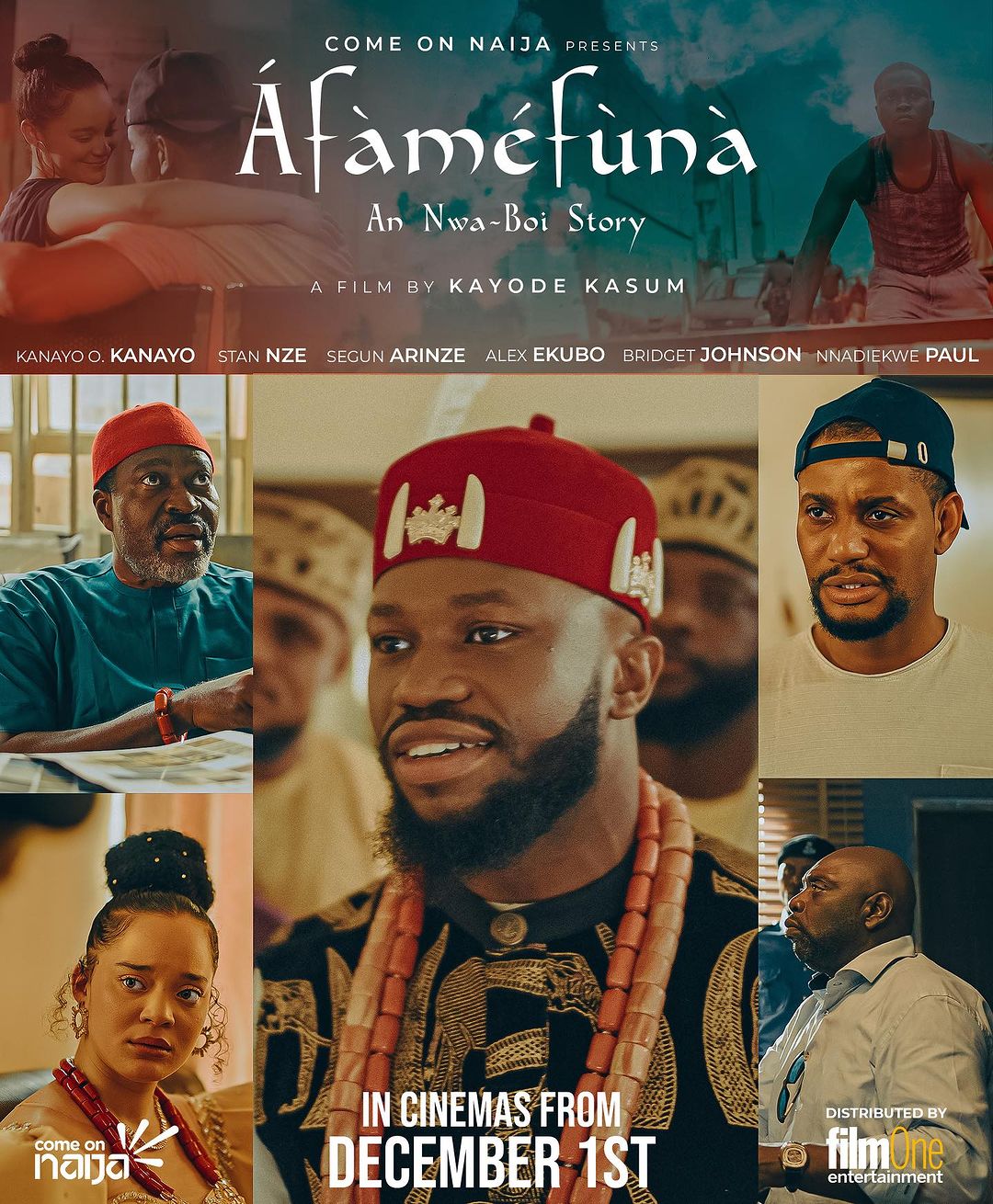

Áfàméfùnà: A Perfect Exploration of The Igbo Culture

I developed an affinity for the Igbo language when I read Chinua Achebe‘s ‘Things Fall Apart’ for the first time. The elegance with which the words rolled off the tongue, the wise proverbs, and the context in which they are used made the language very appealing. However, it was through Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‘s books that I fell completely in love with the language. Unlike Achebe, Chimamanda provides translations for the Igbo words she uses. While reading ‘Zikora’, I came across a character named Mmiliaku, which means wealth that flows like water. At that time, I used to say a prayer that went like this: “Dear God, I want Mmiliaku.” It’s amazing how the words and names are so concise yet so rich and expansive in meaning.

So as someone who is fond of the language, watching Áfàméfùnà, directed by Kayode Kasum, was more of an exploration of admiration. While it doesn’t take away the artistic elements, I was particularly interested in hearing the characters speak Igbo fluently, a difference from previous Igbo movies which were mostly in English.

The movie starts with an exuberant burial ceremony which opens the story of a young man named Áfàméfùnà, robed in his isiagu attire and being sprayed wads of money notes. From the opening scene, the movie settles us into the proper Igbo culture with dances and flutes before an arrest that will usher us into this Nwa Boi’s story.

As a young man, Áfàméfùnà’s (also called Afam) mother brings him to Lagos to learn trade from his uncle, Odogwu, played by Kanayo O. Kanayo. Upon arrival, he makes friends with Paul, who teaches him how to gain customers and become wise in the streets of Lagos. As time passes, their friendship grows stronger, and they start protecting each other’s secrets. For instance, Paul has an affair with Odogwu’s daughter, Amaka, which Áfàméfùnà comes to know about. Although Afam also fancies Amaka, he cannot express his feelings, and can only admire her from a distance. But time will tell if there will eventually be a love story between Afam and Amaka or not.

Áfàméfùnà exposes the audience to many aspects of the Igbo culture. We not only see the modus operandi of the apprenticeship system and the life of a Nwa Boi through the lens of Paul as he teaches Afam, we also learn about its history. As narrated by Odogwu, the Igbo apprenticeship system started after the Biafran War when 20 pounds was accorded to the Igbos in each household. It was from that money they started to conduct businesses and expand. As their businesses grew, Odogwu says, “Many traders started taking in Nwa Bois for trading. After training them, they will be settled with money and shop. They come to their master’s shop to carry goods. The more you sell and remit money, the more goods you will carry. Then the settled apprentice will bring in a new apprentice and also teach them the trade. That’s how it is done. Business will be good. That’s how the Igbo business started growing to date. Whoever doesn’t understand something will be taught by his brother. Igbo people are blessed with knowledge in running businesses.”

The major takeaway from Áfàméfùnà is understanding how the Igbo culture and apprenticeship system work on a surface level. As a Yoruba man, watching the movie makes me realise how well the Igbos run their communities on partnerships, brotherhood and trust. Odogwu says, “The Igbo business empire is built on brotherhood and hard work” He alludes to a proverb that says, “Wherever you go and you do not see an Igbo man, you should run.” Actually, I believe that anywhere you go and you do not find a Nigerian, you should run. But that’s by the way.

According to the rule of this business model, the boss must knight an apprentice, (which is known as freedom), before the apprentice can set up a business. Paul is expected to be knighted but the table turns and Áfàméfùnà is knighted, and this ignites the feud between Paul and Áfàméfùnà. With the knighthood feud in the background, Áfàméfùnà and Amaka get married and Paul, throughout the movie, feels everything that belongs to him is stolen by Áfàméfùnà. That is when the blackmail begins.

From the dialogue, to the scenes, cinematography, and every other artistic element of Áfàméfùnà, we see parts of the Igbo culture amply represented and even explained. From the movie, we understand why women cannot be ‘Nwa Bois’. We also understand why Afam does not hesitate to take Lotanna as his son even after finding out the truth. Using the narration of Áfàméfùnà to tell the entire story is a brilliant move by the director. The cinematographer also did an excellent job of capturing all the elements to help the audience properly understand the apprenticeship and Nwa Boi story. Generally, the movie manages to show us what’s important. The best part of watching Áfàméfùnà, for me, is how comfortable the characters are in speaking the Igbo language, particularly because I am used to watching them in English movies.

However, there are plot holes that beg to be filled. Why does Áfàméfùnà have to allow himself to be blackmailed when the child does not belong to him? Is this brotherly love or the fear of being ridiculed by society? Does Amaka not have the slightest idea that the child does not belong to Áfàméfùnà? Why would Odogwu knight Afam before Paul? Why does the police officer have to make a call in the course of an investigation?

While there are a lot of scenes that beg for answers, “Áfàméfùnà: An Nwa Boi Story” is the perfect art to attract anyone to the Igbo apprenticeship culture. The soundtracks, language, dialogue, rendition of proverbs by Odogwu, and everything else seals the appeal of the Igbo culture. I will give the movie an 8/10.