Features

An Adventure with ‘The People Who Live on the Hills!’ Read About Olawumi’s Trip to Enugu

Some memories last forever, and this particular one will sure be one of those.

Some memories last forever, and this particular one will sure be one of those.

Did you know that Enugu means “The People who Live on the Hills”?

I decided to go by road to Enugu this time because I like the serenity. Me seated by the window, the quickly passing trees, the breeze as it rushes into my face, and the conversations by other passengers.

I have realized that no matter how reserved people are, when they are placed in an enclosed environment, after some hours, they begin to loosen up, contribute to conversations. And when it’s politics being discussed, oh God, no one can resist the opportunity to blame the government for not helping them brush their teeth. This affords me the opportunity to feel the pulse of the people, understand them a little, while I make my contributions when necessary.

I always have a book with me to read on my road trips, and I always seize the opportunity to reflect in the first couple of hours of the trip. The political gist on this trip started in Ore, Ondo State, up until we got to Benin. All of the passengers, except me, alighted. I was headed to the east; the driver put me in a connecting bus to continue my trip. My new co-passengers were quite different from the first set, who were middle aged people who ran businesses. This time, they were all ladies who I guessed were in their twenties.

The trip was quiet, until we had to spend about 3 hours trying to cross the Onitsha bridge. Then they caught the bug, started gisting about the outing they had the night before: How they were so high on Benilyn with Codeine that one of them drunkenly updated her Snapchat; how they eventually missed their flight scheduled for 7 a.m. and the airline was to blame for it. They had gone out with a guy who had paid one of them ₦100,000 for the night, they said. The girl had been tempted to tell her friend, who I guess doubled as her pimp, that she was given ₦50,000. But she resisted the temptation, only to discover the guy had called her friend to find out if she told the truth. “You’re lucky you told her the truth, if not you for no see the guy again for your life,” said the other friend. Now you see that road trips can be fun, as I wouldn’t have gotten this type of juicy gist on a flight where everybody will be forming posh.

I eventually arrived Enugu sometime past 10 p.m., and my host, who I was seeing for the first time this year, treated me to a feast of roasted chicken with mixed veggies and a drink at a beautiful park that shared the same compound with a museum. We visited Okpara Square the following day. While we took photos, to prove that Nigerian policemen are the same everywhere, some officers came and tried it with us. I mean, they really tried it. They told us where we stood was opposite the governor’s lodge, that we were trespassing. But, obviously, all they wanted was some change. When they noticed we weren’t going part with any, they let us go, allowed us to take our photos.

I eventually arrived Enugu sometime past 10 p.m., and my host, who I was seeing for the first time this year, treated me to a feast of roasted chicken with mixed veggies and a drink at a beautiful park that shared the same compound with a museum. We visited Okpara Square the following day. While we took photos, to prove that Nigerian policemen are the same everywhere, some officers came and tried it with us. I mean, they really tried it. They told us where we stood was opposite the governor’s lodge, that we were trespassing. But, obviously, all they wanted was some change. When they noticed we weren’t going part with any, they let us go, allowed us to take our photos.

Next to Okpara square is a beautiful forest reserve where we saw couples taking their pre-wedding photos. We found it impossible to resist taking photos there.

Next to Okpara square is a beautiful forest reserve where we saw couples taking their pre-wedding photos. We found it impossible to resist taking photos there.

My next point of call was to visit Nike lake resort. On the way there, I saw some unique monuments and couldn’t resist the urge to get down from the car to take some photos.

It was a 30-minute drive to Nike lake resort and it was worth the drive. Every bit of the resort had some form of art or the other. The red brick wall and the graffiti wall at the entrance; the lovely layout of trees; the lake with its white birds, their own community meeting on the other side of the lake; and the fisherman on his locally made boat, rowing in search of fish, his net placed in an L-shaped pattern. It was all so breathtaking.

In the hotel lobby I made a new friend called Mr Parrot. We had so little time to bond, as I had to take some time to enjoy a short rest by the poolside in the cool of the evening. I didn’t want to leave but we had some other places to visit.

In the hotel lobby I made a new friend called Mr Parrot. We had so little time to bond, as I had to take some time to enjoy a short rest by the poolside in the cool of the evening. I didn’t want to leave but we had some other places to visit.

The next stop was at the karaoke bar. I heard some lovely renditions of songs from Dido, JAY-Z–90s-era music, generally. The air was thick with nostalgia. Nevertheless, Lagos no dey dull, and so I represented my people by giving my own cover of 9ice’s “Street Credibility” – one of my favorite Nigerian songs of all time. Of course, I got a standing ovation. “You repped us well,” said the guy whose table was next to ours, and I gave him a high five.

The next stop was at the karaoke bar. I heard some lovely renditions of songs from Dido, JAY-Z–90s-era music, generally. The air was thick with nostalgia. Nevertheless, Lagos no dey dull, and so I represented my people by giving my own cover of 9ice’s “Street Credibility” – one of my favorite Nigerian songs of all time. Of course, I got a standing ovation. “You repped us well,” said the guy whose table was next to ours, and I gave him a high five.

Day 2 saw me having the Enugu State version of the popular food called ‘abacha,’ with palm wine – what’s the point of travelling if you can’t treat yourself to some local delicacies.

Then there was the visit to the museum where I learned a lot about our Nigerian culture and tradition,

It was a 1 hour tour, with stories behind each image enlightening. Photos weren’t allowed in the museum so I’ll give you the gist: there were different effigies, all of them representing peoples’ gods. My tour guide called them “personal chi.” Chi in Igbo language means God. Back then, it was in the form an image they kind of worshipped. Like the Ikenga for chiefs and important people, which was split into two when a man died, one half was buried with him while the other remained in the family to serve as a monument for him to be remembered by. The Hausas had the Dakakari portrait. The Ivori for Delta State, symbolizing that the owner was a king. The Okega from Kogi State. Evbuori for Bayelsa State, and Kingabo for Rivers State. They are also called the cult of the right hand. It was believed that it was the force moving a man’s success in life, and if one wasn’t at peace with it, the person would become mentally ill. He also said some parts of Brazil use Yoruba language for their incantations due to the western slaves who influenced them back in the days.

There were divination materials like Oyo – not the state – and Npkurafa for Igbos; OpeleIifa and Iroke Ifa, a bell for yorubas; Bararuwa, the clapper bell for the Hausas; and the Iroro for the Edos. Ritual staffs like the Opa Osayin for the Yoruba chief priests; the Oji and Ofo which is a symbol of fairness that is being carried by the oldest man in the Igbo community. It is said that once a man wass carrying the ofo he had to be unbiased in his judgement or die in the next 3 market days. There were also instruments of warfare from all parts of the country. Ota for the Igbos, Nzami for the Hausas, Eru Ogun for the Yorubas, which was a traditional bulletproof. The tour guide asked why we buy foreign-made bulletproof vests aka Kevlar, when we have locally made bulletproof vests like Odeshi, and I told him to talk to the I.G. Abi? In addition were various spares, swords, and locally made pistols.

There were divination materials like Oyo – not the state – and Npkurafa for Igbos; OpeleIifa and Iroke Ifa, a bell for yorubas; Bararuwa, the clapper bell for the Hausas; and the Iroro for the Edos. Ritual staffs like the Opa Osayin for the Yoruba chief priests; the Oji and Ofo which is a symbol of fairness that is being carried by the oldest man in the Igbo community. It is said that once a man wass carrying the ofo he had to be unbiased in his judgement or die in the next 3 market days. There were also instruments of warfare from all parts of the country. Ota for the Igbos, Nzami for the Hausas, Eru Ogun for the Yorubas, which was a traditional bulletproof. The tour guide asked why we buy foreign-made bulletproof vests aka Kevlar, when we have locally made bulletproof vests like Odeshi, and I told him to talk to the I.G. Abi? In addition were various spares, swords, and locally made pistols.

Then I saw head masks, worn both for war and as a war souvenir. There was the Oya head masks worn by the Abriba people for war, and it was likened to the Spartans where every male must prove that he is a man by going to war. For the Igbos there was the head mask. If there was an inter communal war the only way the men proved that they were an active part of the war was by the number of heads they brought home as souvenirs. So the number of heads a man had in his house determined the level of respect he earned, which was made into the head mask. If you’ve ever witnessed a traditional dance or an exposé where the Igbo dance is being showcased, you probably noticed a group of men shake their shoulders. This symbolizes and mocks the way a victim vibrates when his head is cut off. This is the warrior’s victory dance.

They also had fertility sculptures from various parts of the country. For men, farmers, women, it was all there. There was the Igwaja head mask from Gombe, Ogom from Abia State, Iyalode from the west, and Afor that women had to appease to conceive, as there were no gynecologists back in the days. The fertility sculptures for farmers were to appease the land before planting season commenced. In addition was the Ekpe cult, and behind it was the Insibidi writing which were some codes that could only be deciphered by the members of the cult. The codes were used during the slave trade for protection, and it’s believed that it’s still being used in some parts of Brazil.

I also saw some headgears – not your regular ones, trust me. There was a society called the Gelede, formed by a woman. From what I gathered, domestic abuse from husbands was part of life then. Because of this, Iyalode decided to get powers from the wicked spirits to defend herself against that. Her husband would beat her, I learned, and ask that elders appease her after it all. She needed an insurance plan. She became so powerful that she could manipulate many things, and a part of the history of witchcraft was traced to her. When other women asked her, she initiated them. It however got out of hand and they started using the powers for selfish reasons, including killing children. The gelede cult was formed to educate a woman to reduce her ill will and encourage her to do more good. Because it is said that when a woman is angry, there is chaos in the society. The headgear was worn to appease the witches from killing their children.

I also saw some headgears – not your regular ones, trust me. There was a society called the Gelede, formed by a woman. From what I gathered, domestic abuse from husbands was part of life then. Because of this, Iyalode decided to get powers from the wicked spirits to defend herself against that. Her husband would beat her, I learned, and ask that elders appease her after it all. She needed an insurance plan. She became so powerful that she could manipulate many things, and a part of the history of witchcraft was traced to her. When other women asked her, she initiated them. It however got out of hand and they started using the powers for selfish reasons, including killing children. The gelede cult was formed to educate a woman to reduce her ill will and encourage her to do more good. Because it is said that when a woman is angry, there is chaos in the society. The headgear was worn to appease the witches from killing their children.

In addition, there were prototypes of various masquerades from different parts of the country. For example, the Nwanwuafia had the capacity to dethrone the obi of Onitsha. The nwanwuafia could also remove any woman from her marital home – which became a bad omen for generations; if a woman wanted to get married and it was found that any of her ancestors was chased away from her husband’s house by that masquerade, the wedding was called off immediately. I guess it can be likened to the Osu thing. However, the practice is said to be extinct now.

There were masks that the tour guide likened to Halloween masks, and my guide strongly believed that Halloween was copied from Nigeria. He also wondered why we can easily put on a Halloween costume and not a masquerades’ costume without pleading the blood of Jesus. I told him masquerade costumes, unlike Halloween costumes, couldn’t be bought off the shelf. It required some level of divination and spirituality to pull off. He agreed, saying that a masquerade represents the spirit of the ancestors coming through a man in most cases in Africa.

There were masks that the tour guide likened to Halloween masks, and my guide strongly believed that Halloween was copied from Nigeria. He also wondered why we can easily put on a Halloween costume and not a masquerades’ costume without pleading the blood of Jesus. I told him masquerade costumes, unlike Halloween costumes, couldn’t be bought off the shelf. It required some level of divination and spirituality to pull off. He agreed, saying that a masquerade represents the spirit of the ancestors coming through a man in most cases in Africa.

There were also images of deities that represented our societies. The Igbo are said to operate an egalitarian society, like the Yorubas. They have their kings and respect them. The Yorubas are culturally very respectful but the Igbo man believes every man is equal and will just shake hands with their elders against prostrating like his Yoruba counterpart. It is believed that the Igbos have Jewish ancestry due to certain cultural beliefs. The average Igbo man did not believe in sharing a room with his wife due to the number of charms he had. When a woman is menstruating, the guide explained, the charms could be neutralized.

There was the Nte Olo Akike where the umbilical cord of every male born is put to unify the community, so that wherever they are in the world, when a mass return is called, they will always return home. In addition was the Igbo man’s shrine which serves as a worship center, an educational environment, and a security house where important things are kept. It was home to a lot of history; every item represented an event that happened in the past. Whenever a person reached the level of initiation, the chief priest would recount to them the story behind each item in the shrine.

Next were different types of Ikenga which I stated earlier as the personal chi of an individual. There was the one for cleansing called Okewi Ikenga for the Okpanam people. It was believed that when the men went to battle and killed, the blood of that person chased them till they ran mad. That was until it was discovered that the men from that area indulged in and enjoyed weed which affected their brains.

Next were different types of Ikenga which I stated earlier as the personal chi of an individual. There was the one for cleansing called Okewi Ikenga for the Okpanam people. It was believed that when the men went to battle and killed, the blood of that person chased them till they ran mad. That was until it was discovered that the men from that area indulged in and enjoyed weed which affected their brains.

The Igbo political system involved the centralized, non-centralized, and theocratic system of government. In Onitsha the king is called the Obi of Onitsha. There were also musical instruments exclusively for the king to dance to, and if anyone else did he/she would be fined, and if done secretly, well, that’s death!

I also learnt the story behind some scarifications, aka tribal marks. In the east there are some scarifications that help you identify a person and his title/position in the community. If one came across people with those, it helped to know they weren’t ordinary people and could be trusted too in case one needed to make an enquiry.

There was the ark of covenant called Okwachi for inductions, which must be carried by a virgin.

Next was the Igbo social system where I saw Gigida aka waist beads which was worn by women and was to help them checkmate their weight. It was only worn by the wealthy, as it was very expensive. When a woman was ready to get married, she went through a process called Eru Ngbete which involved her being put in the fattening room for a while to ensure they were looking fresh when paraded naked – as they didn’t wear clothes back then – for men to choose amongst them. They also wore Inja Oku, a set of metallic anklets meant for virgins alone. If a lady who was not a virgin wore them to deceive a man into marrying her and he found out after the wedding night, he would return her to her family and get a refund on his bride price. There were prototypes of masquerades used for discipline/social control – sometimes when a woman wasn’t properly dressed; they flogged her – which is called the Igala masquerade, for entertainment and other things. Part of it is the ‘ijele’ masquerade which is the biggest masquerade ever and it comes out only once in a year in some communities.

Next was the Igbo social system where I saw Gigida aka waist beads which was worn by women and was to help them checkmate their weight. It was only worn by the wealthy, as it was very expensive. When a woman was ready to get married, she went through a process called Eru Ngbete which involved her being put in the fattening room for a while to ensure they were looking fresh when paraded naked – as they didn’t wear clothes back then – for men to choose amongst them. They also wore Inja Oku, a set of metallic anklets meant for virgins alone. If a lady who was not a virgin wore them to deceive a man into marrying her and he found out after the wedding night, he would return her to her family and get a refund on his bride price. There were prototypes of masquerades used for discipline/social control – sometimes when a woman wasn’t properly dressed; they flogged her – which is called the Igala masquerade, for entertainment and other things. Part of it is the ‘ijele’ masquerade which is the biggest masquerade ever and it comes out only once in a year in some communities.

The Igbo man’s traditional economic activities included farming, hunting, fishing, weaving, iron works aka Okwu Ozu, and craft making. The Palm Tree was the most important tree, producing palm wine called Manya Ngwo or Kaikai; palm kennel that’s used for getting palm oil; and a body oil called Adiagbon in Yoruba language. The medium of exchange started with cowries since trade by batter failed, then iron bars, lantern, beads, and finally empty gin bottles – the idea behind it was in its scarcity since it was only the white men who brought and had easy access to it, so 7 gin bottles could pay a bride price back then. Wow!

The last phase was the coal city gallery. A group of British geologists, Hebert Kingston and Kays, discovered coal in Enugu between 1908 and 1909 at the Okuye Stream in Ngwo. They met with the chiefs who discussed some form of social responsibility, environmental impact assessment, and community development in return for the coal mining. They signed an M.O.U that the land didn’t belong to them, and after the mining were to return it to the people. Part of it was the building of the first cathedral in Enugu, which is still functional till date. Coal triggered development in Enugu and is the oldest and biggest state in the east.

The last phase was the coal city gallery. A group of British geologists, Hebert Kingston and Kays, discovered coal in Enugu between 1908 and 1909 at the Okuye Stream in Ngwo. They met with the chiefs who discussed some form of social responsibility, environmental impact assessment, and community development in return for the coal mining. They signed an M.O.U that the land didn’t belong to them, and after the mining were to return it to the people. Part of it was the building of the first cathedral in Enugu, which is still functional till date. Coal triggered development in Enugu and is the oldest and biggest state in the east.

In 1917 the whites came back to perform their social responsibilities which included building schools (Iva Valley Primary and Secondary School, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, etc), churches (Holy Ghost Catholic Church), roads, hotels (Hotel Presidential, Premier Lodge), NTA, etc. After all the story, I had to visit the coal site and see for myself. It was worth the stress. I hiked with my tour guides who I met in the process of trying to locate the site, and I enjoyed the sight of the waterfall that it had become.

In 1917 the whites came back to perform their social responsibilities which included building schools (Iva Valley Primary and Secondary School, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, etc), churches (Holy Ghost Catholic Church), roads, hotels (Hotel Presidential, Premier Lodge), NTA, etc. After all the story, I had to visit the coal site and see for myself. It was worth the stress. I hiked with my tour guides who I met in the process of trying to locate the site, and I enjoyed the sight of the waterfall that it had become.

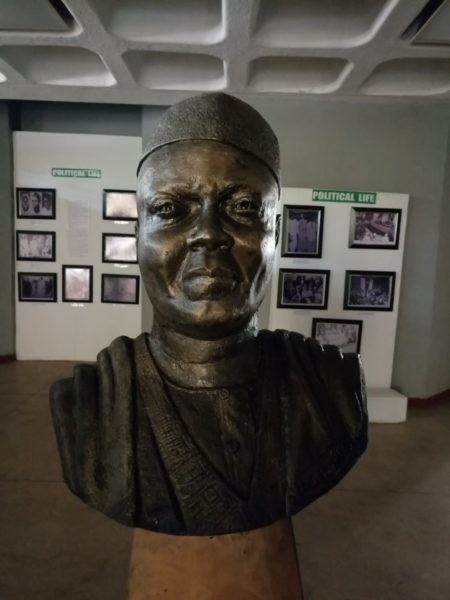

Finally, I had to take a picture with the most prominent leader of the East, Nnamdi Azikiwe’s statue, which was at the entrance.