Features

Cisi Eze: The Dangers of Making Home Uninhabitable – A Review of We Don’t Live Here Anymore

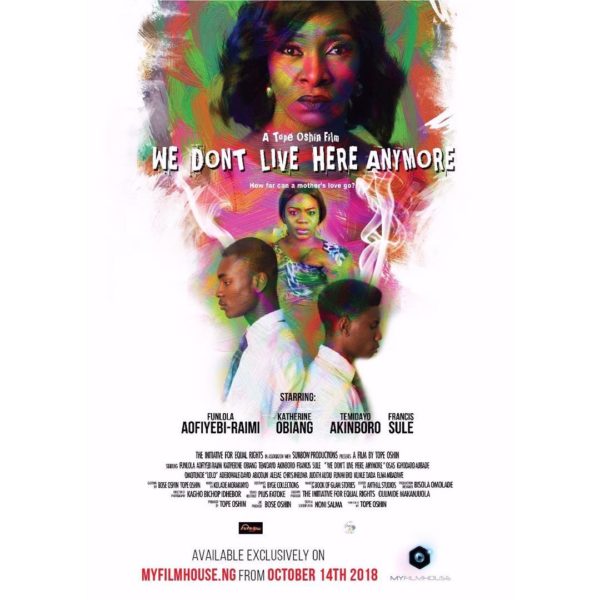

What would you do when your dream suddenly takes on morbid, “abominable” elements to morph into a dreary nightmare? In “We Don’t Live Here Anymore”, a movie produced by The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERs), Funlola Aofiyebi-Raimi’s character, Nike Bajulaye, prances on a crooked path hoping to wipe out the “taint” her gay teenage son smears on the Bajulaye name. Noni Salma spins this enthralling story of two mothers who go all out for their sons, albeit differently. Every scene is beautiful – from the cringe-invoking first scene to the last frame where Tolu Bajulaye (Francis Sule) stares blankly into space. It leaves one begging for more. This Tope Oshin movie is not a story dripping of romance between two teenage boys. It is a sad story. So sad it was for me that my mind would play Erik Satie’s Gymnopedie when there was no music in a scene.

Few of the motifs used to tell this story are family, homophobia, classism, and acceptance. Nike Bajulaye gets a phone call from her son’s school. On getting there, she finds another mother, Nkem Egwuonwu – portrayed by Katherine Obiang, in the principal’s office. He tells them their sons were caught having sex. These women are shocked. With expulsion looming ahead, Nike is triggered to set into motion a dastardly, devious device.

A fan of Michelangelo Antonioni, David Lynch, Tunde Kelani, and Stanley Kubrick, I tend to pay attention to geometric composition, lighting, use of colour, symbolism, and tone of a movie, to mention a few. I felt enough attention was not given to composition. Besides this, I expected that for a movie that sad, there would be more “darkness” in terms of lighting. This would have heightened the mood of the movie. Perhaps, the production team did not want to dunk us in our feelings. The make-up, however, was, well… not the best, not the worst. On the flip side, the music score was befitting. It was heart-warming that the dialogues were very Nigerian and relatable. The casting was good, as all the actors executed their roles well. In addition, there was a slight semblance between Nkem and her son, Chidi Egwuonwu (Temidayo Akinboro).

One of the powerful scenes in this movie was the bedroom scene where Nkem kissed her son on the forehead after tucking him in bed. She had finished cleaning the wounds he got from his former classmates, who had waylaid him to beat the queer out of his soul. As she was leaving his bedroom, he stretched his left hand to hold her hand. She gently turned back to look at him, and their silence screamed a strong message: Thank you for being here. Thank you for accepting me. Thank you for loving me the way I am. Thank you, Mother. Everything about this scene was perfect – lighting, music, etc. When I touched my arm in reflex, I could feel bumps.

How many parents would be accepting of their children? It would seem as though most parents place their own ego over their children’s happiness. On hearing her son is gay, the regular Nigerian mother would blame her new “calamity” on the rice she ate at her neighbour’s during the last Christmas holiday; carry out several deliverance sessions to whoop out the demon; call a family meeting. This was not the case with Nkem. Her love for her son trumped any negative feeling parents feel on knowing their children are homosexual. She loved him so much, and as expected when there is genuine love between parent and child, she accepted him for who he was.

Nike stood out to me among other characters for many reasons, but I will express few. A woman can fake several things ranging from an orgasm to a smile, and Nike did great faking a wide range of emotions. Nike would smile in one moment, and in the next, she would cook up a false cry, leaving us in a state of shookery. “Sis, where did that come from?” Then there was her accent. She sounded like that Nigerian woman who has travelled the world and soaked up several cultures, and now, we find it hard to place her accent. Is it Yorusprenglish? During the post-movie Q and A in the cinema hall, Funlola sounded like how we Nigerians sound, nothing like Nike Bajulaye.

Personally, I would like to imagine Nike’s makeup was another way of telling the story. Then again, this might seem as a reach. From the first scene she appears in, we see her face all caked up, as though she were going to see Queen Elizabeth for a meeting. Guess who has makeup on even at bedtime? Yes, Nike Bajulaye. The tone of her foundation contrasts that of her skin. She wants to look lighter, and we know “lighter is better”. Ask the thriving multi-million dollar bleaching cream industry. Her makeup is a mask, an appearance she must keep. Having makeup on your face around bedtime is uncomfortable, but she does it. This says a lot about how she did the uncomfortable and despicable to save her family name from “shame”. Because her character is well-rounded, we see her take a plunge into the depths of despondence. She stops caring about her makeup and hair. Funlola was stellar in this role!

This well-told story is daring, compelling, and evocative. It sends its message with well-written dialogues, music, proper casting, and mood. It’s a four-star, from me.

Appealing to the empathy of the oppressor in any system of oppression might be a futile step the oppressed takes in the fight for liberation. “We Don’t Live Here Anymore” looks like it was deliberately sad to garner pity from mean homophobes. Then again, we should realise that this is just one way of telling this story. Another way the story could have panned out is that the boys eloped to another country and lived happily ever after. Of course, we want to see more positive and happy representation of queer people in Nigerian movies, however, it has to start from somewhere. Baby steps before giant strides.

The crux of the matter is that stories like this are bound to start conversations: If we claim to love our children, why not accept them as they are? Do we toss our children’s happiness under the bus our egos are maniacally riding on? As Nigerians, are we not tired of making home inhabitable for queer folks in the name of religion and faux-morals induced homophobia? How long are we going to remain intolerant of people who are not hurting us?