Features

Michael Aromolaran: Citation is Simply a Mnemonic Device

Citation starts off with the sun setting on Dr Grillo (Ropo Ewenla) at the Sunrise Guest House, where he had hoped for a Freaky Friday with Rachel (Gbubemi Ejeye), a student he had blackmailed into having sex with him before agreeing to surrender her due class grade. Unknown to the randy academic, his victim has set a trap with the help of a triumvirate that includes her boyfriend. Dr Grillo is dragged to the streets and shellacked in full, public glare before he – in a frantic attempt to escape the mob’s fury – meets a ghastly vehicular end. This results in the students’ rustication from the university, including Rachel’s. The message is lucid: ‘Do not take matters into your hand. Trust the system.’ It is on this premise that the film, Citation, is contrived.

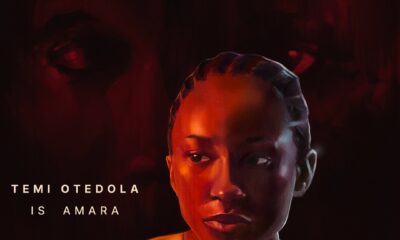

Directed by Kunle Afolayan, Citation centres on a brilliant, 21-year-old postgraduate student, Moremi Oluwa (Temi Otedola), who must convince a sceptical panel that the celebrated Professor Lucien N’dyare had attempted to rape her and unjustly flagged her dissertation as a way of punishing her for shirking his overtures.

What stands out immediately is the Pan-Africanist impression of Citation. It seems like an ECOWAS convention, with Nigeria, Senegal, Cape Verde, and Ghana in attendance – the latter finding expression in the character of Kwesi (Adjetey Anang), Moremi’s avuncular coursemate who when not pining in vain for Gloria (Ini Edo), Moremi’s bestie-turned-foe, is posturing a mirthful defence for the Ghanaian jollof rice. This Pan-Africanism subtly unspools in the scene where Moremi and Professor N’dyare, still in the pre-animus stage of their friendship, prattle names of renowned Pan-Africanist heads: “… Rebels with a cause…Toussaint Louverture… Kwame Nkrumah…”

I think Moremi’s incapacity to function in Yoruba defeats this ‘African-ness’ for which Citation attempts to campaign. While she speaks butter-fluent English and a decent scattering of French, her Yoruba bears a wince-worthiness that seems to shave off emotion and plausibility from Temi Otedola’s acting.

Citation’s strongest point is that it is thematically timely. Coming 390 days after the revealing ‘Sex-for-Grades’ documentary by Emmy-nominated Kiki Mordi and BBC Africa Eye, the film gets some applause for its social activism. I think the flashback technique deployed is effective and that the plot is cohesive, even if predictable, draggy, and hounded by some inconsistencies inspired by, I suspect, periods of writerly sloth from Tunde Babalola, who authored the screenplay.

The casting is, to some extent, commendable, with Ibukun Awosika fitting cozily into her role as chairperson of the Senate panel of hearing which deliberates Moremi’s fate. I also think the cinematography is fetching, but I wonder whether the flashback scenes could not have been enacted with an alternate colouration, perhaps sepia, to set them apart from the present-day scenes.

While Jimmy-Jean Louis plays his role with theatric finesse, in spite of the ‘wig’, Nollywood débutante, Temi Otedola, seems capable of conveying only one emotion: naiveté (if that can be called an emotion). Beyond that, her face, which implausibly wore the same detail of make-up through the film, is mostly a blank sheet of expressionless paper, made more obvious by the close-up camera shots. Temi Otedola does not give an outrightly bad performance, it’s more within the neighbourhood of ‘Switzerland’ – neutral.

Then there is the scene where Professor Ibukun Awosika humbles a jittery Professor N’dyare by reading him a laundry-list of her scholarly victories. She tells him that she is not only a Rhodes Scholar with two PhDs, but has been previously nominated for the Nobel Prize in Economics. This sounds catchy, until you realise that the Nobel Prize maintains a ‘fifty-year secrecy policy’ that prevents it from revealing the names of nominees, not even to the nominees themselves until fifty years have elapsed.

Citation can perhaps be argued to be a celebration of African culture and architecture if you are willing to overlook the fact that “The African Resistance Monument”, one of the goodies vaguely captured during Moremi’s class field trip to Dakar, is the creation of a Romanian architect and North Korean contractor. Regardless, the near-idyllic tribute that it pays to the surroundings of Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, is nearly sufficient to persuade members of the Nigerian political class that sending their children abroad for college education might no longer be necessary.

In the end, Citation manages to contradict its thesis, as the university’s bureaucracy does not actually save Moremi. The Senate panel of hearing is not shown to expend any investigative rigour in disentangling fact from fiction, and is mostly prejudiced in favour of Professor N’dyare, until Moremi’s bold and closing blitzkrieg. Akin to Kiki Mordi’s BBC Africa documentary, courageous acts of individualism, rather than an efficient system, wins Moremi the justice she deserves.

Citation reminds us of the prevalence of sexual harassment on Nigerian campuses, but it lacks both the visceral quality and artistic subtlety necessary to spur any impassioned and sustained discussion. You should watch it, but only because it functions as an effective mnemonic device.