Features

Is Everything About Life Hinged On Luck?

There’s acid in your stomach, bile in your throat, anger in your heart, and war in your head. Your mind is raging with ideas like alates around a fluorescent light, yet you have nothing concrete…

Years ago, on one of my visits to my father’s plantain farm, I met his worker, Oka, and his family of 7. I knew Oka long before I met him. My mother, when going to the farm, would collect used children’s wear, bags, shoes, and books from my neighbour, packs of noodles, and a few food items, stuff them in rice sacks, and take them along.

I saw poverty on a different level when I met Oka’s family. Their home on the farm was made of bamboo, had a thatched roof and no door. There was no bed and they slept on the uncemented floor. His children looked haggard and hungry. Their eyes ran into their sockets and their stomachs pushed forward a little, away from their slender bodies. They weren’t attending school or learning any craft. His wife, beautiful and always smiling, looked frail. Her bones formed long stripes across her chest. I watched Oka’s baby cry, the wife grabbed her and placed her mouth on her dry breasts. The family bought food on credit and on days the seller refused, they ate eba and water, roasted maize, or plantains.

Oka didn’t see anything wrong in the way his family lived. He wouldn’t let his wife look for a job and insisted she worked on the farms and fry garri for sale. He also wanted 14 children, and constantly threatened to marry another woman if his unwilling wife wasn’t ready to have more kids.

She died while giving birth to the 8th child.

–

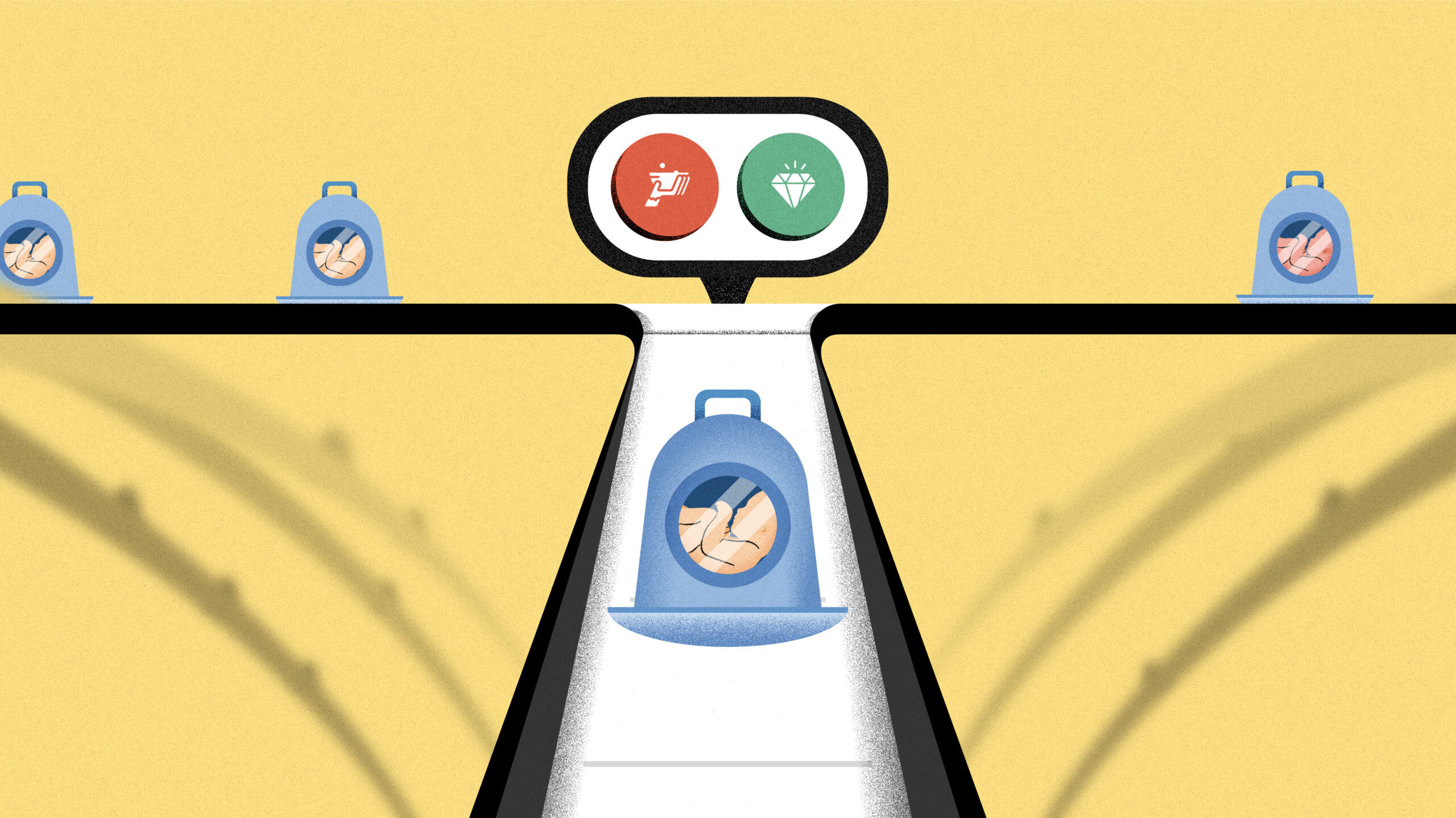

The lottery of birth fascinates me. Every time I think about it, I am enthralled at how being born into a certain kind of family can make or mar, build or break a person. The homes we’re born into decide the trajectory of our lives. It influences the bigger things like the kind of opportunities that’d come our way, our social circle, our way of thinking, if our skin colour will be globally accepted, or if we have to fight to remind the world we are humans too. And then the basic things like whether we’d eat eggs every day or once in a year, if we’d brush our teeth with toothpaste or charcoal, or our feet will be sore because we have no shoes to wear. It decides who we are and has a huge role to play in who we eventually become. Yet, we do not even have control over it. We’re simply lucky to be born into what we may consider to be the right home, and every other thing we do in life is then hinged on this luck.

I often think about Oka’s kids and what the future holds for them. Indeed, we cannot predict how we’ll turn out and who we’ll eventually become but every time Oka’s wife had a baby, I felt pity for the baby. I also felt fear, for the hardship that awaited them.

–

We are in a world where everyone has a piece of advice for poor people: work hard; don’t sleep; save more; don’t try to keep up with the Jones. Then we have the cliche “no one wants to work these days” and “poverty is a thing of the mind”. These pieces of advice are great, but it often shows we do not acknowledge our privileges nor do we understand what poverty truly means. Let me add that poverty isn’t a mindset thing; it is people’s reality.

I wasn’t born rich, but I had an education up to the tertiary level. I never had certain kinds of meals, but I ate. I didn’t have the finest of clothes but I didn’t wear rags. When I sit with myself, I acknowledge my privilege. Without it, I may not be here today, writing this essay, earning a salary, or mapping out career plans. My education opened doors for me, it helped me think better, and plan better. Having a career helped me dream better and want more. This is a privilege; one Oka’s kids may never have.

Dr. Ola Brown once said, on Twitter, that poverty isn’t only a lack of financial resources, it’s isolation from the kind of people who can help you make more of yourself. I’ll also add that poverty isolates one from ideas, good thought processes, and peace of mind. It drains one’s strength and sucks one’s confidence. Our social sphere – the people we meet, talk to and roll with – is often based on circumstance. Being born into poverty means being born into a culture of constant fear, doubt and timidity, so you find yourself cowering and hiding. Your self-esteem is in shambles, and you think so little of yourself. You grow up wanting more yet fearing, even believing, that nothing good can come out of you. You find yourself settling for less because you are terrified to want, to hope, to ask. There’s acid in your stomach, bile in your throat, anger in your heart, and war in your head. Your mind is raging with ideas like alates around a fluorescent light, yet you have nothing concrete. There’s nothing to hold on to. You don’t want to be too hungry because something in you is telling you not to dream too big; you may never get there.

And you are not wrong. UNICEF says that no matter where they are, children who grow up impoverished suffer from poor living standards, develop fewer skills for the workforce, and earn lower wages as adults. Research shows that a child born into a poor family today will take from 4 to 5 generations to reach the average national level of income. For many people born into very poor homes, becoming successful takes triple effort. While you are trying to worm your way out of poverty and fighting for every single thing you get, your mates have gone miles ahead. How, when, and where we are born, grow up, and live is so profoundly and widely unequal that these inequalities will live with us for decades.

But all hope is not lost. If you didn’t win the birth lottery, you can still win in life. The people we become, the lives that we lead, and the beliefs and values that we learn to hold, owe much to the lottery of our birth, but this doesn’t mean we have no control over how we turn out or who we eventually become.

I believe the first thing you must never do is give up on life and on yourself, or spend your time wallowing or dreaming about what could be instead of what is. The trick is to move, no matter how slowly, not in comparison to people who have different kinds of ‘privilege’, but in comparison with where you are coming from and who you were before. The goal is to look back, see progress and realise that even with the little resources you have, you keep making something out of your life. It would be miserable to look back and realise you’ve spent the bulk of your time blaming your parents for your woes or complaining about the unfairness of the world. There’s room for that, but it shouldn’t take the entire building.

You must understand the incredible strength of your mind, question the forces that formed you, and live from a place of compassion for yourself. Let yourself breathe even as you push for more. Let go of the obsession to be at a certain point at a certain age, and find your place in this world.

I am learning this too, so it’s important to tell you that these are words, and words are cheap. What is expensive is deciding who you are. Once you do this, you become unstoppable.

I’ll leave you with Rainesford Stauffer‘s essay on Catapult; my all-time favourite. Like Oka’s children, I think about Rainesford’s words all the time.