Features

Mo! Sibyl: Daddy’s Girl – Healing the Fatherly Wound

There have been two kinds of little girls in the world – those who grew up without daddy, and those who did.

There have been two kinds of little girls in the world – those who grew up without daddy, and those who did.

But there is a third kind, rarely named, who grew up with a father that didn’t feel like a daddy.

We all have gotten an earful of the critical role of mothers in nurturing children. Conveniently left out of this narrative, though, is the impact of fathers, especially on their daughters. The interaction between a father and a daughter goes a long way in shaping her life: her view of the world, her self-confidence, her emotional, physical, spiritual, and mental health. Without a balanced relationship with my father, I grew up deficient in all those areas.

Like most men in his generation, my father’s discipline often meant corporal punishments, and I grew up with an unhealthy fear of him. But even that was less damaging than the lack of play time and words of affirmation, which heightened my fear of my father into anger and then disregard. It got worse: I was whisked away to boarding house when I was 10, and the physical distance in my teens mirrored the emotional gap from childhood. By university, my dad basically talked at, rather than to, me.

Not until recently, in a long-awaited conversation with him, was I able to realize none of that was an intentional attack on my person: just his way of preventing us (especially me, being the only female and all) from turning out bad. His reasoning upon the disclosure is something I probably would not have ever understood by myself but for therapy. Through therapy (which I have been participating in off and on for five years now), I was able to understand the radical acceptance of him and most importantly, of myself.

Because of how I grew up, I never felt loved enough and always thought I had to be the best at everything to get any attention. My emotions were anchored to my dad’s: if he was angry, it was my fault. But nothing he did or said TO me hurt as much as what he did not say or do WITH me, like never hearing a word of affirmation.

As a girl, your father is usually your first male relationship, and so underpins all subsequent male relationships, and not just romantic. Even my image of God was affected. I could not wholeheartedly imbibe the Lord’s Prayer in Sunday School when it spoke of a loving, present father. Prayers that began, ‘Dear Father’ were lost in translation to me, and I preferred to begin, ‘Dear Lord,’ instead. On the rare days I confessed God as Father of love, it felt like a lie. Yet not until recently (after a class on Re-imaging God taught by a Korean Professor) did I realize the connection between my experience of God and my experience as a girl without expressed fatherly love.

In my teenage years, I would go through the angst phase of defying authority, especially of men. Looking back now (I promise I have come a long way from this old me; most of my mentors and benefactors are men), it made a lot of sense for how I was directionally opposed to men because I was transposing my relationship with my father on them.

For girls like me, we avoid, at all cost, marrying men like our fathers, but the irony of the situation is that we probably end up doing exactly this or if yet unmarried, would most likely will. So, take for example, if your father neglected to be empathetic towards you as a child, you might attract men with this similar trait because you are unaware of what empathy should look like.

I did have some protective factors that helped make up for what I thought I lacked, like other positive male role models through school, church, and some of my friend’s dads. By observing these people, I was not only able to contrast the dysfunctionality surrounding me, but got a glimpse of what a healthy relationship with a male (especially fathers) could be like.

My decision to use therapy to explore myself more was probably one of the most important decisions I ever made in my life. My daddy issues had become a comfort word I would spit out as a crutch for everything I did not want to take responsibility for in my life. Moreover, these issues became more chronic and apparent when I got married; I realized that I needed to save me (and ultimately those around me) from doom.

Of most concern was my need to maintain a certain high level of performance in all I did (I saw the world as white or black and could never explore the grey lines). I also always had that insatiable need to keep doing more and more and could never have an appreciation for things I had achieved. Like a monkey, and a mindless one for that matter, I swung furiously from one branch to another without giving time for being in the moment and practicing mindfulness. I also realized that I had gone from being a victim to a villain in my relationships as a result of the unhealed wound in my heart. Simply put, I was becoming exactly like the man I told myself that I did not want to be like, and as a result, I did not like the reflection of the person I seemed to have become.

During one of my many therapy sessions, my therapist suggested I explore the idea of writing a letter to my dad or talking to him, I told her I could never bring myself to do this. So, I decided to work on my anger towards him instead, and this melted away to indifference and was sustained for a very long period until much recently when it changed to acceptance. Because I was not afraid for my personal safety, a part of me felt that I could talk to my dad about all of these issues but I just did not know how.

In December 2017, a little pin-hole-like window of opportunity came up, and so I pried it open. It started with a WhatsApp message to him which cascaded into a series of events that culminated in a two-hour-plus face-to-face conversation (perhaps the longest stretch of time I have ever spent with my dad).

Understandably, my dad was not receptive to my approach and its content, at first. The fear of most parents, I assume, is learning that they were not as perfect as they thought they were. But slowly, with the intention of moving forward positively, we were able to make headway. It came down to was letting him know why and how all he did impacted my life. During this sit-down time, I learned more about him before he was dad. This really helped me get a better framework for his actions. Not unexpected, he grew up with a disciplinarian who was equally emotionally unexpressive.

In getting to know my father, I was able to acknowledge him for the things he did better than those who raised him. An example of this was how very provident he was. He (and my mom) sacrificed a lot financially to make sure that we (the kids) got the best of what they could afford to give us. Instead of growing up in a fancy house and in a less ghetto neighborhood, my parents (especially dad) worked hard to send us to the best private schools in the area.

Their sacrifice paid off as it was the foundation that made every achievement I have now possible. It is why I can write this logically for you reading this and dream of greater heights in my career and other forms of expressions. By talking to my father, I was able to glean that his job (he worked all his life for one of the major Nigerian banks) was mostly responsible for taking him away from home all the time. Even when he was home, he was hardly home, and he had to resort to his style of parenting to have a commanding presence when he was not around, especially. At the end of the day, it all came down to guilt. Like most parents, my father has some regrets about his absence, and as much as I would like to keep tugging at these strings, it would not do much for what I think is most important – the future that lies ahead of us.

These days, Dad and I talk more often. If you had a chance to read our WhatsApp chats, it would read like banters between long lost friends who just reconciled, with a sprinkle or two of the father-daughter type talks. He and I are exploring and getting to know each other better. The unhealthy fear I held in my heart for him has since dissolved, and these days I come from a place of intentional curiosity to get to know him more, and he is quite reciprocal with this too.

So, here’s my summary:

– No parent is perfect, and most people grow up with some form of dysfunction – some more than others. As a result, do not try to aggrandize all that you have gone through. Explore the fears and hurts from those experiences with a therapist, spiritual leader, or both. This exploration might yield a lot more changes in you than you can imagine.

– You are loved, regardless of what you can or cannot do, and can actually begin to believe this truly for yourself. Pending when you get to this realization, do not buy into that lie you tell yourself that no one is capable of loving you and as a result, you keep doing things that compromise your safety or worthiness.

– While you must have become a victim (and could very well still be) due to some of those experiences, it is highly possible for you to also take on the duality of being a villain. And until you confront that monster or Id that was borne out of those hurts and take responsibility for your own actions (instead of blaming whoever the villain is in your Lifetime® movie), progress will hardly be made.

– When that time comes to actually talk to your dad about those issues, consider writing a letter first about it. Put down all the things you need to say and imagine reading them out to him. This is especially important for emotionally sensitive ones like me – I cry unproductively when I am hurt and overwhelmed.

– Do not think of the meeting as an end-all-be-all but like a continuum of some sort. Don’t be under pressure to say everything in one seating but say as much as you can when you can. This also helps the other person not feel like they are being attacked.

– Know that you cannot control the outcome of the meeting. You should create a space in you where you don’t get shattered by not hearing or getting what you want. Your dad might apologize or may not, and your relationship might be worse than it previously was. All I am saying here is that you should be OK with either of these outcomes. You made the first move towards reconciliation and gave it a shot, and to me, that is a very brave move, and I (and the others in your life) will be proud of you for this already.

– Open up to friends and loved ones around you when you are about to do this. I talked to some of my girlfriends, and they were very helpful in reading and editing my letter to my dad to make it as less emotional and more factual as possible. To these friends (you know yourselves), I would like to use this medium to thank you from the deep crevices of my newly-transplanted heart.

– Forgive him: it would further help to reduce the level of control he already has in your heart. After all, when we forgive others, it is more for us than it is for them.

Getting rid of this daddy-sized baggage did a lot for me spiritually, mentally, emotionally, and especially productivity-wise. The decision to give back the baggage that was never mine created space for me to be more productive, which eventually led to me launching my podcast a few months after. It also made me be less miserable to those around me. I realized that my propensity to love others grew deeper and more importantly, I was extra gentle with myself in the areas I was lacking.

We often hear that people never change, and I used to be a firm believer in this but no more. Not with what I have seen in my dad and especially my own heart. We can chalk it down to ageing (his mortality and mine staring us both in the face) or grace; regardless we have both left that space we once were and are now working together towards a better future. While I cannot say ‘I love you’ to my dad (hey, I did say I was a work in progress right and these things do really take time?), I can say ‘I have you now,’ and that’s a pretty pretty pretty (in Larry David’s voice) good way to start.

Happy Father’s Day to us all!

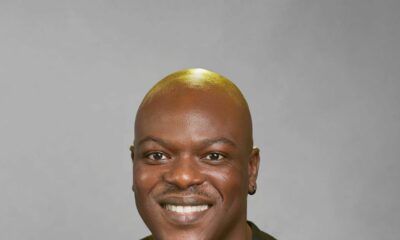

Photo Credit: © Olena Yakobchuk | Dreamstime.com