Features

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: Gidi Blues is an Average Film Elevated by a Supporting Role

Sometimes an actor in a leading role is outshined by one in a supporting role. This is the story of the film Gidi Blues, which has two very good looking women in lead and supporting roles. One (Nancy Isime) takes her chance, the other (Hauwa Allahbura) doesn’t quite. It is particularly a masculine conceit that in the film, both their characters are looking to get the same man. Allahbura wins the battle. Isime will win the war.

Sometimes an actor in a leading role is outshined by one in a supporting role. This is the story of the film Gidi Blues, which has two very good looking women in lead and supporting roles. One (Nancy Isime) takes her chance, the other (Hauwa Allahbura) doesn’t quite. It is particularly a masculine conceit that in the film, both their characters are looking to get the same man. Allahbura wins the battle. Isime will win the war.

The film opens with a theft at a Lagos market. No problem there even if that’s a cliche: big city and crime go together at the movies. The film then tries to shift from this opening cliché but drifts into the extended cliché of a cinematic love story.

I’ll explain. The theft of a lady’s handbag propels Akin (Gideon Okeke) to go after the thief. There’s a bit of a finely-shot race through the market, a tricky thing to shoot anywhere in Nigeria. Our hero gets into a den of hoodlums but is rescued and given the handbag. He returns it to the lady (Allahbura).

At this point, the viewer knows Akin and Ms Handbag aka Nkem, will meet again and begin the process of movie-romance. This is exactly what happens.

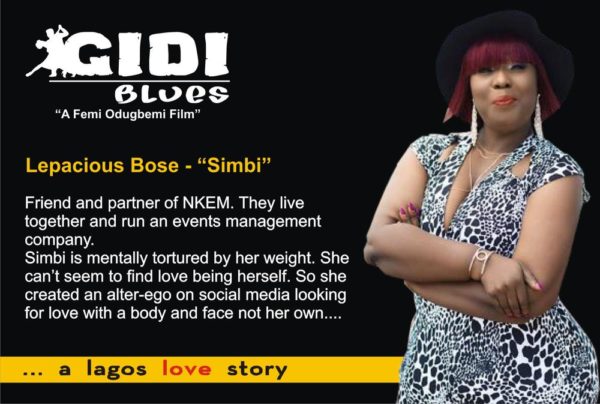

There is, however, a side story involving Jaiye, Akin’s friend, and Ms Handbag’s friend, Simbi. There is also another featuring Akin’s mother (Bukky Wright) demanding that her son finds a wife. To help him, she hooks him up with a girl (played by Isime) from “a good family”, the Nigerian parent’s dream. But of course, our hero will meet his damsel-in-stolen-handbag-distress again.

Gidi Blues works with the classic romcom format. Boy meets girl, boy and girl fall in love, trouble shows up in paradise, boy and girl reunite. So Gidi Blues is the kind of film you watch less for surprises than to find something new injected into an old format. Here, that something new is Lagos.

In many stories about Lagos, love is dessert. A lot is made of the city’s crime and hardship, and in recent times our directors have gone for that part of their city. Daniel Oriahi had robbery and prostitution in ‘Taxi Driver‘. Walter Taylaur‘s ‘Gbomo Gbomo Express‘ had kidnapping. Violence and vice, we are told, are the main dish in the city of Lagos. Femi Odugbemi, the film’s director, has chosen as main course an item on the last page of the menu and in small font: love in Lagos. By introducing difference into the typical Lagos story, he has also brought Lagos to the love story.

Unfortunately, Odugbemi’s method of bringing Lagos to the love story is to highlight the Lekki bridge. The film showcases the famous bridge heavily, but the tawdry flick ‘Fifty‘ has already worn out whatever novelty that bridge has for Nollywood viewers. Coming only a few months after the Mo Abudu produced film, Gidi Blues cannot claim first position in showing Lagos’s architectural jewel on the big screen. You wonder why shots of the bridge are even necessary. Our filmmakers seem to think that tourism in cinema must be used as weapon to beat the audience over the head with. To make it even less appealing, there’s also a rather unnecessary but well-meaning Makoko documentary added onto Gidi Blues, in the name of giving “life meaning.”

In any case, the film is handsomely made. The camera is handled well, if too self-consciously, on many occasions. And there are quite fine scenes, with just enough colour. The film uses too many close-ups, however–which reminds you that our director has been working on television for a while. His relationship with Africa Magic, which sponsors the film, means that Gidi Blues will end up on the small screen.

The choice of close-ups may be argued but Odugbemi’s main failing here is hard to defend. Technically a good director, he isn’t, from this evidence, much of an actor’s director. He allows his principal actress get away with too much in doing so little. To be blunt about it, he gives his film’s weakest actor the second-biggest role. The film almost crumbles around her.

In several scenes, Okeke amplifies his movie-star-charm only to see it bounced back in his face in a way that only a truly beautiful woman can manage. But a beautiful woman is different from a good actress. Gidi Blues needs both to be believable. It only gets a beautiful woman. What comes off the screen is not chemistry but a working relationship between two actors. Okeke is blameless here; the fault is in the casting of the female lead.

Movies have always needed pretty faces that know that know they are pretty or can ignore that knowledge as soon as the camera shows up. The first conveys a self-awareness that can be sexy and perhaps limiting; the other is the making of a likeable or versatile actress.

At the moment, Allahbura isn’t ready to be either one. She gives the facial equivalent of a speaker who doesn’t know what to do with her hands. Do you put it on the podium? Do you leave both hands by your side? Do you wrap them around your body like protection from your audience? In the end, such a speaker may wish she has no hands. With Gidi Blues, the lead actress seems to wish she had a less pretty face. She can’t forget she’s beautiful, but the knowledge of her own beauty does nothing for her acting. She’s a beauty queen but no goddess. It may be easier if she had no face.

Elsewhere, the scenes with Isime as Carmen and Okeke’s Akin sizzle. You might come to think it is possible to wipe off steam from the screen–if you could reach it. Isime’s approach to playing her character recalls a comment made about Marilyn Monroe: “she threw herself at us with the off-color innocence of a baby whore.”

Carmen is supposed to be a pastor’s daughter. But as Ajebutter 22 reminded us in on the song “Omo Pastor“, a pastor’s child has needs too. This one has sexual needs, and Isime makes a cool drink of it.

A comparison should help. If Joke Silva and Iretiola Doyle, two of Nollywood’s most respected actors, have made the female Nigerian the prototype strong, highly responsible and rigid human even in their most risqué roles, they can also be said to have made her a frigid, don’t-f*ck-won’t-f*ck creature of the boardroom and parlour. Isime’s Carmen is different as she reclaims the bedroom as a place also made for the woman. Her ancestors can have the office. Hopefully she won’t be typecast.

She is the admirably slutty-sister/nutty-offspring of Bimbo Akintola in Out of Bounds and a host of Yoruba-Nollywood heroines who go for their man in the sheets and on the streets.

Sadly, Gidi Blues doesn’t understand the origins of this character, how revolutionary she is. She is shortchanged by screenwriters Taiwo Egunjobi and Femi Kayode. An attempt to offer redemption in her last scene comes too late.

Instead it becomes Isime’s weakest scene. Her role is small and the damage is set and done before her terminal scene. Akin calls her character a pornstar in what is very well a misogynistic label. He never gets called out for it. This is a reflection of the Nigerian society. And perhaps the way she’s treated is merely meant to show how Nigeria treats a sexually aware woman.

Yet you wonder how much it says of the filmmakers’ own politics when Lepacious Bose in her role as Simbi, the boy-crazy sidekick to Nkem, talks about wanting to be slimmer. (In real life, the comedienne has indeed become slimmer.) With the inclusion of this bit in the story, it becomes harder to defend the politics of Gidi Blues. The perhaps unintended ‘wisdom’ of the film’s depiction of women is simple: Happiness for Woman is a fragrance promised to only the slim and the sexually pure.

Surely, the makers of Gidi Blues would want us to forget its backward gender and sexual politics. It’s possible that we might forget–if only because their film will come to be remembered for providing a flawed but important take on our idea of the Nigerian woman.