Features

Osisiye Tafa: Beauty Is Fleeting

What do you call beauty, and how does time affect this?

I saw her eyes, innocent and liquid, and she was gone.

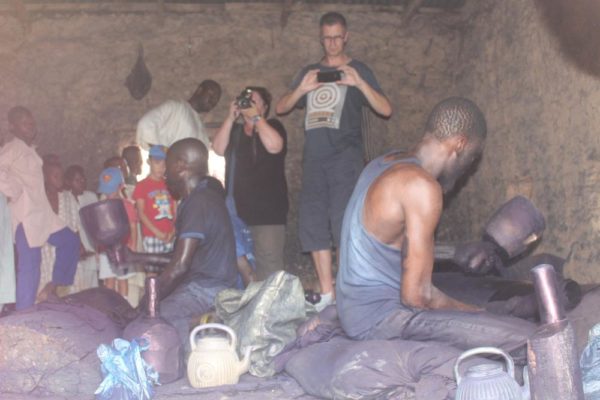

We are in Kura, Kano, a sleepy, dusty town popular for its dyeing pits and cloth spinning factory. ‘Factory’ here is a dank, dark room made of mud bricks with two opposing window shutters that are permanently open. Two men sit inside beating clothes with wooden hammers over a wooden log.

A horde of screaming children with dusty faces surround us. This is normal because my travel partners are white, and for some reason, the kids in Kano seemed to always lose their heads over this. I prod through the throng of children to find what I had just seen. My black privilege allows me to sift through the kids easily, they are uninterested in me, I am the average ‘Yakubu’ down the street, with a fancy camera.

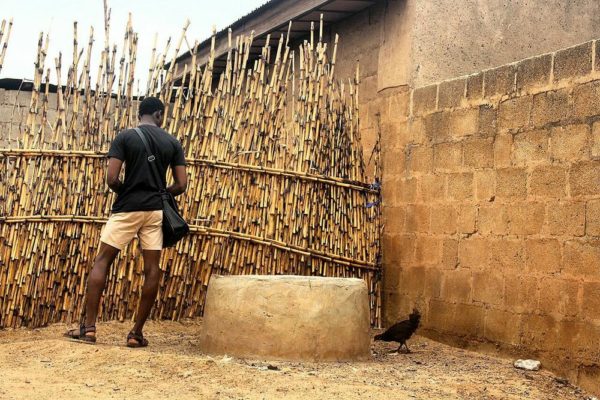

I see her again, this time, a pink veil and she is gone. Then she peeks out and smiles. I am happy about the turn of events. She is not shy, else she would have run into one of the mud houses around. She is interested in us, the visitors, and this game has to go on. We have checked out the dyeing pits, the block making factory and now I am looking at the fences, they are a golden brown colour, made of something like dried raffia.

I see her again, this time, a pink veil and she is gone. Then she peeks out and smiles. I am happy about the turn of events. She is not shy, else she would have run into one of the mud houses around. She is interested in us, the visitors, and this game has to go on. We have checked out the dyeing pits, the block making factory and now I am looking at the fences, they are a golden brown colour, made of something like dried raffia.

A black hen is pecking around my foot area and there is a well beside me – very deep as you find them in these parts. Then she surfaces, smiling, with her dusty face, wearing some lipstick, probably applied by her older sisters. She still has that shy smile and I politely ask for a picture which she agrees to and then she is gone. Beauty is fleeting, you miss it if you blink, you have to move fast to get it or sometimes, just stand still and it comes to you.

Beauty is fleeting, you have to make it, and what we call ‘beauty’ is a figment of the imagination. The dyeing pits at Kofar Mata could be underwhelming – if you notice the flies, high prices of the apparels and remember that clothes are dyed in the pits for months. Also, people drink the used dye water from the pits to cure stomach ailments and typhoid, but you have to ignore these and remember how old this structure is. It has existed since the Europeans coming.

Close your eyes and listen to the tour guide, even buy a stupid cap.

Beauty is something you have to work for. Climbing the steep incline at Tiga was uneventful for the first 50 meters till a stone castle came out of the undergrowth. Beside the Tiga Stone Castle is an abandoned boathouse, with blue and white fading paint.

In front of the castle, blue railings lead down to a lake that looks like a sheet of blue glass placed on a patch of grass. Around it, goats and cows graze while a large shepherd dog, that looks like a cross between a boerboel and Labrador, snaps at their heels. A red boat is at the bank, empty. Beyond it are the outcrop of rocks scattered all the way leading to the beach. The rock arrangements are like a maze game, they have no order to them, and look like a giant dropped them absentmindedly man while walking to the lake. We picnic on a rock close to the lake. The dog has stopped snapping and is now walking among the cows.

The herdsman’s two sons are having a swordfight using their long herding sticks as swords (or sabers if you prefer Star Wars). It is time for the afternoon prayers and the herdsman bows, the lake in the background, the deserted red boat rocking softly beside him. Inside the deserted boathouse, a couch made of brown fabric collects dust.

There were slight drizzles, so Rano Rock, a smooth easy looking climb proved treacherous. It is a black outcrop amongst wide, green farms, its blackness is a mix of water on the rock’s surface and green, wet moss.

There were slight drizzles, so Rano Rock, a smooth easy looking climb proved treacherous. It is a black outcrop amongst wide, green farms, its blackness is a mix of water on the rock’s surface and green, wet moss.

A few steps in and a large Shepherd dog, this should be a mix between a German Shepherd and a local dog which had been earlier mixed with a larger breed, charges at us from the rock’s summit. A slender boy of fourteen, runs after him screaming in Hausa (or Fulani). Large shepherd dog is not going to attack the mountain climbers, but by God he is going to have his fun; so he charges down the rock into the farms.

Slender boy of fourteen pursues him, screaming and laughing in the local dialect. Large shepherd dog stops, wait for slender boy of fourteen to catch up with him and charges off again. As we climb Rock Rano, we can hear the excited chatter in Hausa mixed with the barks. At the summit of Rock Rano, the farms spread out before us, manicured with neat ridges. Beside us, a group of girls laugh shyly, we ask for a picture. At the base of the mountain, a bike is parked at a jaunty angle. We descend the rock and drive through the Rano community.

We are at the palace, in the chamber where the Emir sometimes holds court. There’s a gilded, huge chair in the center and down both sides of the room are chairs. It is well lit and my legs sink into the red plush rugs. Before now, I had learnt the history of turbans, two tufts at the top means the wearer is royalty/related to the Emir. The room holds a mix of turbaned men and foreign delegates, the air is awash with accents. Then it starts, a cry that sounds like a mix between a muezzin’s call for prayer and a woman in the throes of passion. It is the padawa’s chant, calling out the Emir’s praise as his procession is about to begin. The turbaned men tap us, it’s time to head out.

We are at the palace, in the chamber where the Emir sometimes holds court. There’s a gilded, huge chair in the center and down both sides of the room are chairs. It is well lit and my legs sink into the red plush rugs. Before now, I had learnt the history of turbans, two tufts at the top means the wearer is royalty/related to the Emir. The room holds a mix of turbaned men and foreign delegates, the air is awash with accents. Then it starts, a cry that sounds like a mix between a muezzin’s call for prayer and a woman in the throes of passion. It is the padawa’s chant, calling out the Emir’s praise as his procession is about to begin. The turbaned men tap us, it’s time to head out.

Everyone heads out and the turbaned men form two lines at the entrance of the inner palace entrance. There is a long trumpet note, then drums, then flutes. All this while, the padawa chants and screams: about the Emir’s forbears, his majesty, his powers. The air is magical, full of expectation, of something bigger than now. More turbaned men come out of the palace entrance and a graceful beast of a horse darkens the entrance. The emir in a red brocaded flowing dashiki, a gold and red cap balanced on his head at a jaunty angle sits atop this, his arm raised in a tight fisted salute with his thumb pointing upwards.

Everyone heads out and the turbaned men form two lines at the entrance of the inner palace entrance. There is a long trumpet note, then drums, then flutes. All this while, the padawa chants and screams: about the Emir’s forbears, his majesty, his powers. The air is magical, full of expectation, of something bigger than now. More turbaned men come out of the palace entrance and a graceful beast of a horse darkens the entrance. The emir in a red brocaded flowing dashiki, a gold and red cap balanced on his head at a jaunty angle sits atop this, his arm raised in a tight fisted salute with his thumb pointing upwards.

The air is electric. The emir is loved and there is really nothing more beautiful, more graceful, than the Emir of Kano, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, also known as Emir Muhammadu Sanusi II, the grandson of Muhammadu Sanusi – the 11th Fulani Emir of Kano – the direct son of Ambassador Aminu Sanusi, from the Sullubawa clan of the Torobe Fulani.

Now the padawa had been joined by two others, wailing, singing, there is drumming, the horn about the length of a car continues to blow. The Emir heads to a large outer court, still within the palace. For 2 hours, he will sit in this court while the heads of the 44 wards and their families would come to pay their respect to him.

We are in the outer courts. The Northerners are hospitable; they push the foreigners (us) forward first. We look drab in our formal shirts and t-shirts compared to these Northern turbaned men. We bow, but the Emir shakes us. We take our seats in the large hall where all around turbaned men sit, lean, crouch while an endless number of families come to bow before the Emir. He takes special notice of the young turbaned boys and calls them forward for a head pat, to ask for their names, to bestow them with greatness. This goes on for hours, we are offered malt, a sugar high to ward off the ennui and even after that, the malt wears off and the ennui settles. Women are not present for this, they are herded off to be with the Queen.

After hours, we return to the inner chambers for lunch with the Emir, a delightful event. After that, the Emir would ride out to his mother to pay his respects and then return to the palace, where the heads of all the families would proceed before him on their horses, charging, displaying performances of magic, dance, canon shots, animals, apparel and colour.

I would like to tell you about the many things I saw, a charging horse with a ward lord clothed in full finery, the man that swallowed fire, the one that bore a live crocodile across his body like a baby, the polo player, the hunters with their canons going off in timed sequence to their leader who rode on a horse in front of them, the shared moments between families as they watched the procession in awe, the kids arriving excitedly in their Friday best, the silence amid the horses hooves and horseman yells like water cupped in a leaf long after the rains but beauty is fleeting and what felt like beauty then might not feel like beauty now and the things I leave out might be beautiful to you.