Features

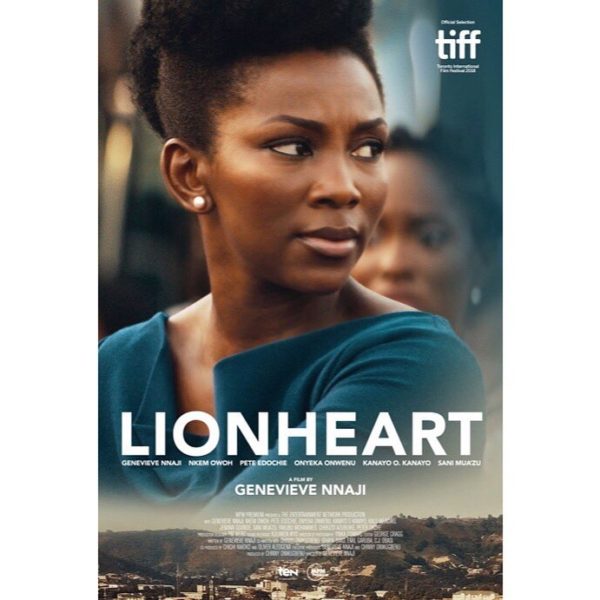

Gideon Chukwuemeka Ogbonna: Lionheart – More than Your Average Nigerian Film

To tell a story is to give a gift. In whatever form it comes (music, film, or book), storytelling gives us the chance to sit and view life—what it was, what it is, what it can be—from a big screen, or from words laced within pages. With Lionheart, Genevieve Nnaji tells a Nigerian story in pure form, transporting us to the hilly clime of Enugu where a young lady, Adaeze, together with her uncle, Godswill, team up to rescue her father’s transport company from bankruptcy.

To tell a story is to give a gift. In whatever form it comes (music, film, or book), storytelling gives us the chance to sit and view life—what it was, what it is, what it can be—from a big screen, or from words laced within pages. With Lionheart, Genevieve Nnaji tells a Nigerian story in pure form, transporting us to the hilly clime of Enugu where a young lady, Adaeze, together with her uncle, Godswill, team up to rescue her father’s transport company from bankruptcy.

The many reviews on social media about this movie makes it almost hackneyed to still say that Lionheart is a good one. Ms. Nnaji scored a lot of points with the directing and overall production of this film. It was refreshing watching scenes that were relatable, true, and typical depictions of the Nigerian life; scenes set neither in Lagos nor Abuja, but in Enugu, a place I am sentimentally attached to.

Lionheart was packed with legendary actors who didn’t force anything, who took up their roles effortlessly, making it seem as if there was a hidden camera, and no director to bawl, “Cut!” “Action!”

We must give kudos to Ms. Nnaji for trusting our wits and understanding, for trusting us to see intricate details like the signpost bearing “Ministry of Transport” as Adaeze hurried into the building instead of telling us that the meeting for the BRT contract was held in the state secretariat; for telling us, in the early scenes of the movie, that Enugu to Shagamu was running low on passengers, and showing us later why that was so in the scene at Peace Park.

She trusted us with the beauty and power of language at the Obiagu’s lunch table where they teased themselves, sharing meals and laughter, dishing out jokes in rich, exhilarating Igbo, one so exhilarating that a non-Igbo wouldn’t feel the need to demand an interpretation.

She trusted us in the scene where the sing-song dialect of Hausa calmed the palpable tension of ethnic sentiments that hung in the room as Chief Obiagu and Alhaji Maikano sat sharing drink and kolanut.

Also, in a time where the issue of gender equality is one met with misconceptions and criticisms, where many have made the words “feminism” and “misandry” synonyms, there is need to applaud the feministic undertone in Lionheart. It passes the important message that assistance or teamwork doesn’t downplay a woman’s strength, that it doesn’t matter who gets the job done (man or woman) so long as the job is done, that we can recognize and respect the choices of people as much as we respect our culture.

Lionheart gifts us a quintessential character in Chief Obiagu, a titled, wealthy Igbo man who allowed his daughter take full charge of his empire while his son took up a “trivial” career path—music.

However, despite the many positives of Lionheart, it is difficult to sideline its flaws. A story is important, but how it is told is more important. Lionheart was a weak and predictable story devoid of twists and turns, and filled with typical Nollywood tropes and clichés. I had expected that a movie such as this would be fast and furious, a crescendo to a beautiful climax. We saw Ms. Nnaji do this with the movie, Road To Yesterday. Sadly, what we saw with Lionheart was a film that had its story rushed, robbing the audience an opportunity to savor the beauty of it, the beauty that could have been birthed out of it.

There was the needless need to make it so thematic and didactic that the pace of the movie was slowed down so as to accommodate—overburden—the movie with themes such as love, family, mentorship, discouragement, and renewed vigor. Themes passed only by the protagonist in a way that downplays the strength of the villain. I believe that if the villainous characters of Igwe Pascal and Samuel had been fleshed out better, it would have provided more richness to the story.

Furthermore, Nollywood movies haven’t gotten it right yet with hemming themes with scenes. This is why we keep having apparent plot holes: because writers always fall into the trap of creating extra, most times, implausible scenes just to pass a particular message. We see this in the scene where Adaeze and her uncle went to meet Arinze for assistance. That was a forced, implausible scene. Why would her uncle just opt and go into a part of a house he was visiting for the first time? Say there was a background where the Godswill character was depicted as troublesome (such as we have seen many times with Nkem Owoh’s characters), then it would have made some sense.

Also, how did Adaeze suddenly know where her uncle was? A man she told to wait outside because she wouldn’t take a minute? The whole scene waters down the quality of the story, and I think it was just a ploy to get Peter Okoye featured in it. It should have been scrapped, a better way found to pass the message of “Not All Igbos Are Swindlers.”

But overall, Lionheart is more than an average film. One that, once again, puts Nigeria in the map. And we are thankful for the gift of Ms. Nnaji. A beauty in all ramifications, except for her voice though. Her “Wetin you go do your best friend” line was a hilarious throwback to her “hit” single, “No More.”