Features

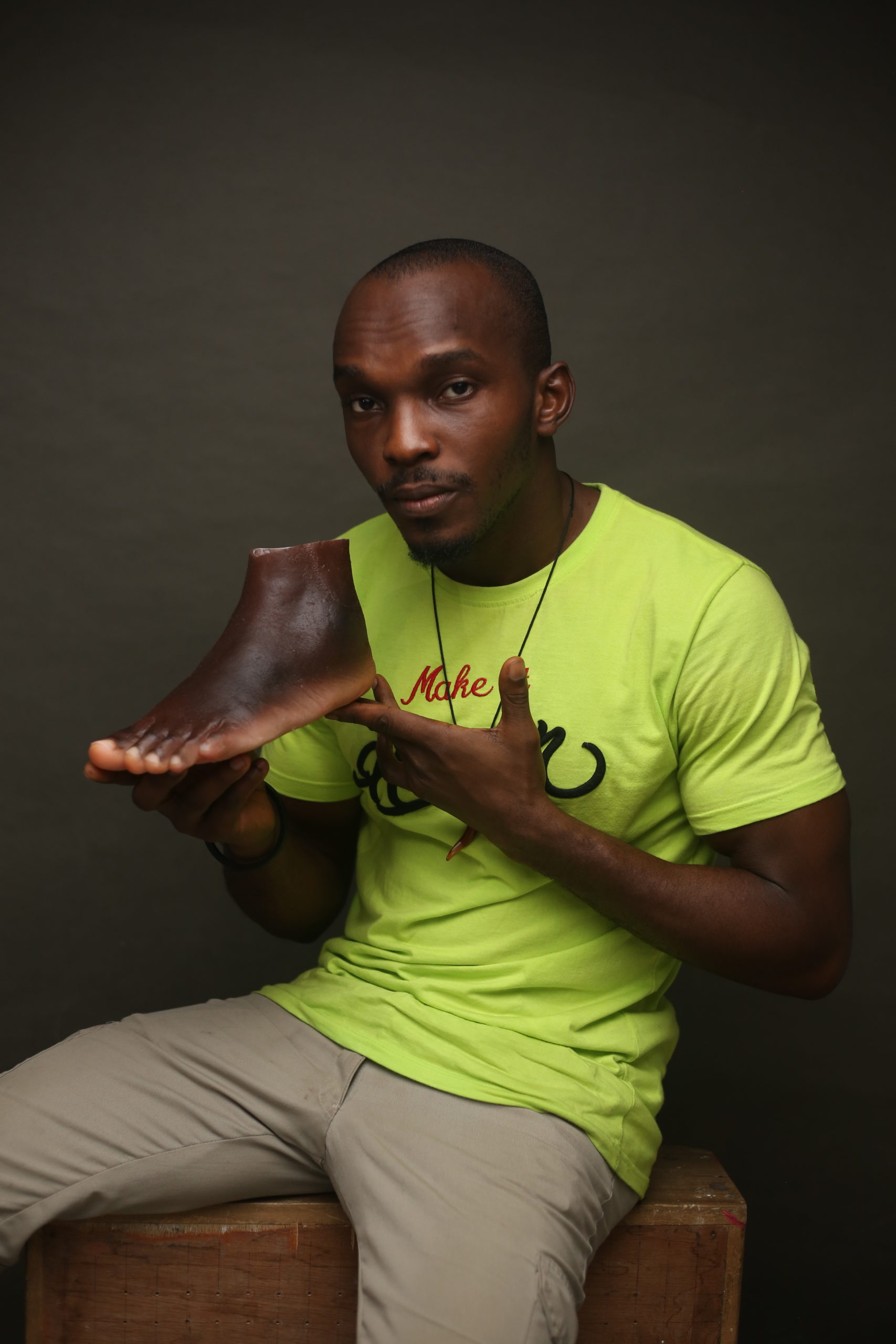

John Amanam’s Hyper-Realistic Prostheses Are Giving Amputees a Semblance of Their Body Parts

John Amanam is “happily married to art.” Having studied fine and industrial art at the University of Uyo, and becoming a sculptor and visual artist, his path was already clear: he’ll be that artist the world would dote over. But there’s something he did not know: sculpting was not what would make him a renowned artist, making hyper-realistic prostheses was.

When John graduated from the university, his plan was to make art people would love. But this plan took a different turn when his brother was involved in an accident that claimed one of his limbs.

I didn’t have a plan to go into prosthesis-making. I didn’t have passion for it nor did I have it as an ambition. The production of prosthesis came along the line; I ventured into it out of necessity.

As an artist, you will be exposed to different forms of materials, and processes of production. As an industrial artist, I ventured into prosthesis when my loved one had an accident and lost part of his palm. Having had a pre-knowledge of certain materials and certain processes, I decided to go into prosthesis making to solve that need because it was very necessary at the time.

I’m self taught, I did several researches and experiments before I arrived at the standard I wanted.

In Nigeria, John’s prosthesis-making skill is unmatched. His silicone, manually adjustable, hyper-realistic prostheses have all the markings and colours of natural body parts, and they go beyond aiding people who have lost body parts to giving them a semblance of their natural body parts.

Before John began making prostheses, he was a sculptor and a visual artist. His gift of making sculptures and visual art, and his general knowledge in industrial art helped him in making hyper-realistic prostheses.

Art is something I inherited from my father, and from my grandparents. Art made me succeed and blend in into the production of hyper-realistic prosthesis. As a sculptor, I was into realism and actualism and that also helped me in the success of the prosthesis.

After John made a hyper-realistic prosthesis for his brother, things took a different turn, and there was no turning back.

After I made my brother’s prosthesis, I moved on. But I started receiving calls from foreign numbers. People were saying “we’ve seen your number online, people are talking about you.” I didn’t know I was the only one doing hyper-realistic prosthesis at the time; I thought there were other people already doing it. But I went online after some months and saw comments about my work. I thought “wow, so this is a serious business.” So I did my research and realised there was no Nigerian or African doing hyper-realistic prostheses. I realised there was a market, so I set up the business and registered the company in 2019.

John’s company, Immortal Cosmetics, where he has up to 15 staff is always buzzing with clients calling from different parts of the world, and making orders for his hyper-realistic prosthesis, and this is good for John.

It’s been very interesting. I’ve been exposed to the world. I have received calls, been mentioned, and gotten clients from more than forty countries in the world. Every week, we have enquiries from at least 7 different countries.Initially, I did not have patronage from Nigeria(ns). I had more publicity from western media and more clients from western countries. I began to be patronised by Nigerians when BBC Pidgin did a mini documentary on my prosthesis-making.

John has done well for himself and being a prostheses maker has been beneficial. Before his fame, John used to struggle as a sculptor, especially in getting people to know and pay for his works. But since he started making prostheses, it has shed light on his sculptures, added more value to his artworks, and led to more patronage. Now, people give him contracts to make statues, and pay for his works no matter how expensive they are. John makes money from both the sale of his artworks, and the making of prostheses.

Still, it is not all scented candles and roses for John and his team. Being the only hyper-realistic prostheses-maker in Nigeria can get overwhelming at times, and it seems he cannot catch a break. “There’s always a deadline and a client waiting,” he says.

That’s not the only challenge John goes through. Making prostheses in this part of the world where we do not have enough facilities to support productions like this also comes with its own hazard: you have to import most of your materials and partner with a lot of foreign companies.

We don’t produce the frame (which is like the prosthesis support), we only partner with some companies and individuals who do. That’s because producing the frame means we have to do entirely different research. What we produce is the flesh cover to cover the frame.

When it comes to the production of hyper-realistic prostheses, people are still researching, learning and discovering. Sometimes we buy materials from a particular company and after a while, we realise it’s not working and we have to abandon it and look for another material. The process of the research is more expensive than other things, especially since there is no existent research work. So you buy this and buy that, try this and try that just to achieve that realism.

I‘ve also come to terms with the fact that I’m now a prosthesis artist. So I need to constantly upgrade, carry out research, travel or send people out to do research – keep up with the game. The world is competitive.

The emotional struggle was also there at first.

People come out from the hospital and you see different kinds of accidents, injuries and different kinds of deformities. I wasn’t used to such sight so it was very hard for me at the beginning.

John does only customised prosthesis that goes with his clients’ skin tone and sizes, and the process of making hyper-realistic prostheses is also an expensive one. Some of his protheses run into hundreds of thousands of naira, still, John says that compared to others, the prices of his protheses are cheaper by half.

The prices fluctuate because all the materials are imported. The quotation we give our customers who make enquiries expires in a month. Prices of prostheses differ. Presently, for ears, it is 200,000 naira and above. Fingers are between 90,000 and 120,000 Naira depending on where the finger amputation is. The foot is between 450,000 to 500,000 naira. The hand – below the elbow – will cost about 600,000 to 650,000 naira.

I’m also not comfortable with the fact that prostheses are expensive, especially when I think of the poor and how they cannot afford 400,000 or 600,000 naira. It’s one of the sad parts I have to come to terms with. But we need the money to keep moving and producing.

To get a hyper-realistic prosthesis from John, you have to travel to Uyo, the capital of Akwa-Ibom State.

We have clients come to our facility. We take their measurements, and take the cast of their body part that needs prosthesis. Then we work on that measurement. We give you a time frame which is usually 2 months or more. A finger will take about a month. We give this timeframe because of the workload we have and because we want to be sure that we deliver quality products.

The good news, for those who have to travel from other states, is that you don’t have to travel when the prosthesis is ready; John can have it delivered to you. However, you are welcome to come get it yourself, especially if you want to test it there to ensure that it fits.

Another good news is that with your prosthesis comes a manual.

We give manuals to help the user use the product properly and to take care of it.The products last between 2 to 10 years, depending on how the clients take care of the product.

There’s one bit of information John ensures he tells all his clients though, “We are not God so don’t expect us to give you exactly what you lost. But we can give you 75-85% of what you lost.”

John has come a long way and he is as proud of himself as we are of him. On building his company, he says “I didn’t think it would go that far and that fast. It would be bad to announce yourself to the world and then you can’t meet up. I congratulate myself.”

Although John is a G in this field of prosthesis-making, he hasn’t forgotten his first love: sculpting.

I am more proud of myself as a sculptor, and more passionate about sculpting. I’m an artist, prosthesis just came along the line. I’m planning an exhibition around November or December so my followers can see my real expressions, and to remind myself of the sculptor I was before prosthesis-making came my way. Without the sculptor in me, prosthesis art is nothing. The prosthesis-making part of me, although also artistic, is the problem-solving part of me and the sculpture-making part of me is the more creative and expressive part.

The exhibition is not the only big thing John has planned, “I have other ideas that when I share it to the world, they will be shocked,” he says.

But John has spilled the beans a little, and now we know that he has no plan to remain “too active” in prosthesis-making for a long time, so he wants to build a system that can run itself. He wants to have at least 20 patents before he leaves the earth, and in the coming years, he’s looking to build a school of prosthesis – an academic environment where people can learn everything about making prostheses.

With these grand plans, the world may become “shocked,” after all.