Features

Oluwadunsin Deinde-Sanya: “On Black Sisters Street” is Teaching Us To See People More

When it comes to talks of sex work, we live in a two-faced, two-perspectives world. There is a stark difference between the reception sex work has in the “real world”, and the perception people have of it on social media. In the former, it is condemned and the women who are involved must be from the pit of hell. They are bottom-barrel women who trade their virtues for a few coins, and do not deserve anything good. Tufiakwa to them. On social media, they are over-glorified: women who are bold to challenge the status quo; women who are gunning for what they want; women who are not fazed by the stones cast at them, nor will not be shamefaced into letting go of this supposedly very lucrative craft. These women are carefree, living the life and everything seems rosy.

But like blackness in the eyes of western media – where you must be either royalty or slave, fetishised or obscured – when we talk of sex workers, we, in many ways, strip them of their humanness or reduce them to props. For many, the over-exaltation of sex workers is not because they think so highly of them, it is used to pass across the message of women owning their bodies, and then used to score cheap points against those who think otherwise. And when we condemn them, it is because we do not think of them as humans, as people with dreams, as people worth knowing beyond tight little skirts and lingeries, and we narrow their whole existence to their night activities. Such a shallow way of thinking.

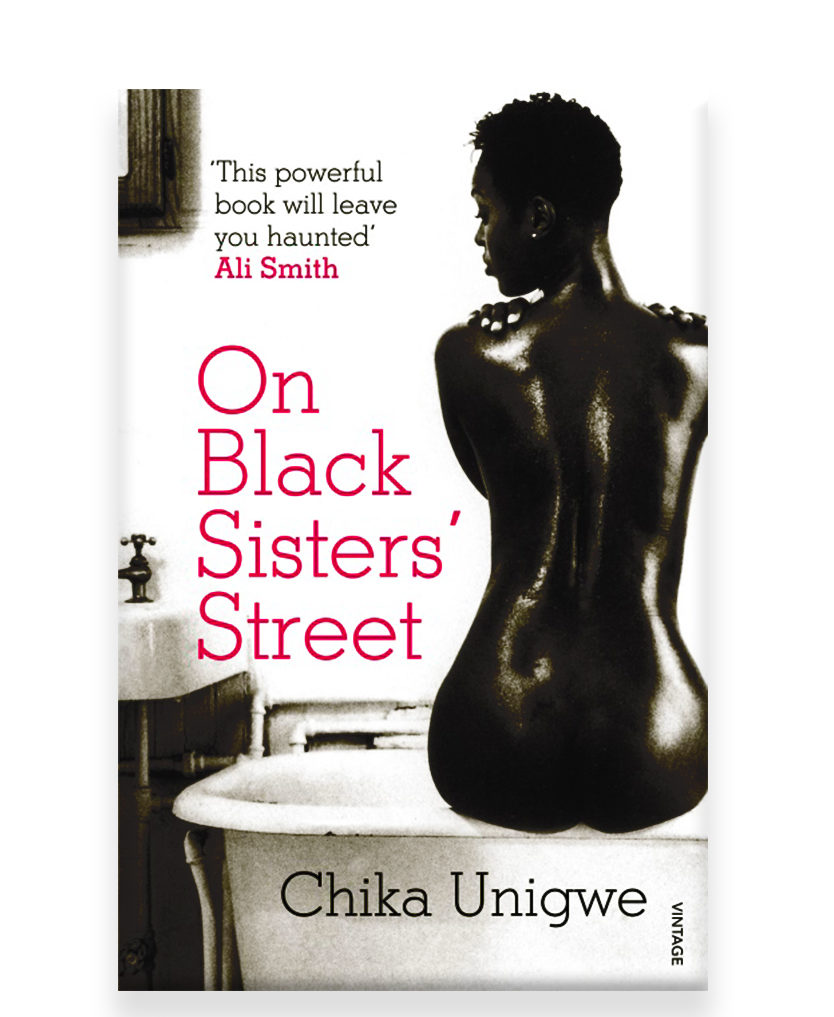

I have always been a sucker for listening to, knowing and telling people’s stories. Perhaps that is why, long after reading Chika Unigwe’s On Black Sisters Street, I am still thinking about the book.

In On Black Sisters Street, 4 women are low-life prostitutes, worthy of nothing except sexually servicing up to 15 men a day and fattening the already-deep pockets of their pimp – until they open up their hearts to one another after the death of one of them – Sisi.

On Black Sisters Street may not be telling us something new about the world of sex work. After all, we see sex workers every day, we know they almost always have a pimp, we know about workers hanging by the roadsie catcalling potential clients, we know the stories of drugs, strippers, killers and what not. Chika, instead delved deeper, beyond what the characters do, into who they are, and in a world filled with too many judges and jury, this is who we all should be: story-hearers and, perhaps, tellers. People who should be willing to hear other’s stories before hurling condemnatory words at them.

In reading the book, I found myself in Sisi, Ama, Efe, and Joyce – ambitious women who are hungry for more. Women with dreams, wishes, fantasies, and hopes for brighter futures. Theirs is a story of resilience and grit where many would have cracked and fallen; the determination to keep pushing, night after night even when freedom looked unreaching. A story of shared humanity where many would have become beasts in a world that keeps clogging their insides with sorrow and pain.

And yet, their stories are not entirely unique to them – they are so similar to many other sex workers out there, the problem is that many people are either too judgemental to listen, or to self-absorbed or self-righteous to understand. Perhaps if we listened to these people more, we’d see their dreams and beauty, the love and loyalty they carry; we’d see who they are as opposed to who we think they are.

This is not just about sex workers, it is about extending grace to people – to those you’re shushing because they aren’t on your level, to workers you’re extorting because there’s a high level of unemployment, to the driver whose car you bashed and are intimidating with “do you know who I am”, to those who are doing legal work but you term “immoral”. To extend grace is to not trample on an already fallen man, it is to love people beyond their occupation or social status, it is to tuck condemnatory words beneath our tongues.

For me, On Black Sisters Street is a reminder to see people more, to hear them more and to know them beyond the world’s perception of them.

Chika writes, on her Instagram post: The writing of this book changed me. Researching it taught me patience and empathy, and showed me how blinding privilege can be. And that shame is sometimes a luxury. And that joy can be found, sometimes, in the most unexpected places. And beauty where we least expect it.”

And that sums it up.