Features

How a Small Steel Box is Changing the Lives of These Women in Rural Ghana

How to save when the nearest bank is many miles away? For these women in rural Ghana, the answer is simple: work together and use a cleverly conceived steel box.

Memunatu Salifu watches her daughter-in-law cook as she sits in the centre of her courtyard in the small town of Sagnerigu in northern Ghana. She’s up early to get ready for the day before heading to the local shea processing centre to process her orders for the week. Shea is the family’s economic lifeline.

Salifu is about to eat her favourite breakfast: tuo-zaafi, which is a local dish made of maize and eaten with ayoyo, a green vegetable soup.

As Salifu waits for her daughter-in-law, her son is preparing to head to the local market where he will trade his fowl. The trade is his contribution to the upkeep of the family. He emits a high-pitched sound to entice the fowl with grain before capturing the big ones.

Salifu, a widow and mother of five, lives comfortably compared to many in the village; she has a business and a five-bedroomed house. Though the house is not fully complete, she is spared the constant anxiety of struggling to raise monthly rent. At the processing centre, other women, most of them shea seed sellers, tell her how lucky she is.

“Naawuni zogo, nyin gbam ma. Ti gba di nya ayili maa, ti na vogue.” (“Salifu, you are a lucky woman… we wish we had a house like yours.”)

But she often dismisses such remarks when she looks back at what she went through after her husband died. Left on her own—and still grieving—with five children to feed, clothe, and send to school and, on top of that, pay rent, she was not sure what fate had in store for her.

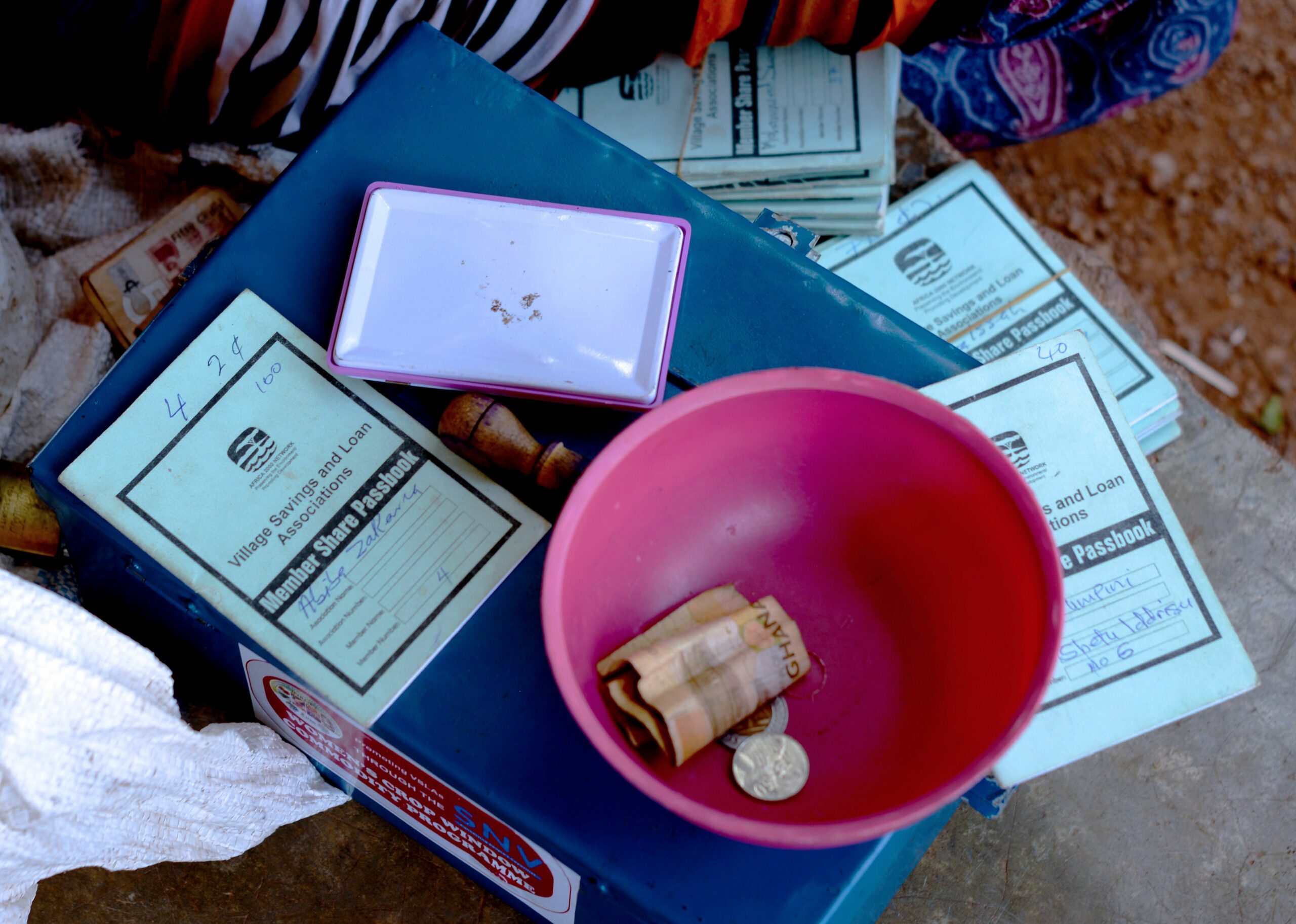

Salifu said that all she could manage was to take one day at a time. Her only source of security was a little metal box. The Adaka Billa (small box) is a communal savings box that helps groups of savers in villages across Ghana save and manage their money. It works like a village bank and is making a big difference in the lives of many people in rural areas, especially women.

Initially introduced to small-scale traders wanting to save and borrow at minimal interest, it has opened its “doors” to all people—including the unbanked in both rural and urban communities—who not only lack access to banking but also the collateral to borrow from formal institutions.

For Salifu, it has been a slow but progressive journey. She initially borrowed from the Adaka Billa to buy the land on which she later built her home when her spouse was alive. She started building, but she ran out of money before she could roof it. She went back to the little steel box to borrow more to complete her project.

“I borrowed money with interest from the Adaka Billa and used it to buy two bundles of roofing sheets; my son likewise bought two bundles, and we managed to roof the house and move in,” said Salifu.

Salifu isn’t the only one who has been spared the humiliation of financial insecurity. According to trader, Sanatu Mohammed, the steel box enabled her to purchase school supplies for her child to enrol in high school. “I borrowed money from the box to buy groceries for my last child, who had earned admission to Tamale Senior High School last year,” she said.

While Salifu is widowed, Mohammed is dealing with the cost of care for a bedridden husband and children, and no amount of money could be spared. Salifu and Mohammed are both small-time traders. Their days are filled with making sales and saving money so they can invest.

The Sagnerigu residents are beneficiaries of the little steel banking system run by 90 women.

“This system allows us to start small and grow our little savings from our daily sales. Borrow to address immediate family needs such as school fees, medical expenses, expand business or invest in income-generating projects,” said Mohammed. “It is also our fallback insurance when crops fail because of rain and we have a food shortage.”

According to the project coordinator, Tahindu Damba, the idea, which targeted women, was to inculcate in them a culture of saving and investment in a community plagued by financial challenges despite their hard work. “The traders were living from hand to mouth because they had no idea how to save. So, we helped them to enhance the money box concept, which some of them were trying to use,” said Damba.

However, the conventional money box in Ghanaian homes lacked security features. A steel box was to be fabricated by a local welder. “We were advised that if we saved in a bank, we would need three signatories to offer optimal safety for our savings. So, we localised the concept, purchased three padlocks, and distributed the keys to three distinct women,” Salifu revealed.

A daily savings of 2 Ghanaian cedis (GHS), the equivalent of 20 US cents, was decided upon by the women. Salifu says she had saved up to GHS 300 (nearly US$30), making her eligible to borrow to complete her project.

However, the purpose of adaka billa goes beyond just advancing individual goals. According to one of the group’s leaders, Abiba Zakaria, it also provides women with a sense of agency and control over their lives. “We utilise our funds to address our immediate needs and investments. It has really changed our lives,” she explained.

To keep track of their daily savings, all members are provided with a booklet to record either their daily or weekly savings. Initially, this was a challenge, but with time, the members have become adept bookkeepers. “We were taught how to record our daily savings and how to deposit the money in ‘our bank’ each week,” said Salifu.

Saving money in a money box is nothing new in Ghana. The moneybox challenge, which is largely for those who live more comfortably and can afford to pour a few cedis into the box, is a social media phenomenon in which groups of women show off their savings at the end of the year.

Unlike other saving practices, however, the adaka billa sees the box handed to one member of the group each month, rather than personal savings being kept in the home. The small box provides choices and security. Over a thousand people are currently involved in the adaka billa movement throughout the north, from shea processors to tailors, mechanics, food vendors, and commercial vehicle owners.

Salifu and the other people in the Pasung Sha Processing community in downtown Sagnerigu don’t have to worry about school fees and medical bills for themselves and their families anymore.

Even though Adaka Billa began as a project for small-scale women traders, it has grown and now includes people from all over the informal economy.

Last year, the three groups, comprised of male artisans with a membership of 90, saved a total of GHS 324, 000.00 (nearly US$ 32,500). Each member’s daily average was between GHS 10 and GHS 50.

“With the money I saved last year, I took it and bought a 13-seater bus, locally known as 207, which has boosted my economic power, ” said Alhassan Yakubu, a vehicle mechanic.

The adaka billa is spreading beyond Sagnerigu to the neighbouring Abofu communities in the Ashanti region and parts of the Bono region, all in northern Ghana. “I believe that in the near future, the little steel box system will soon be the first port of call for those in the formal sector who need to borrow money. Perhaps it could even lend money to the government,” concluded Damba, with a smile.

Photo/Story Credit: Zubaida Mabuno Ismail for bird story agency.