Features

Fridah Njeri Transformed a Faltering Floating Restaurant into a Tourist Site in Kenya

A view of the floating restaurant in Lamu island, Kenya. Photo Courtesy: Fridah Njogu

There are no land rates for this bar and restaurant that floats on the sea waters of Lamu Island in Kenya. People have lived here for over 700 years. Lamu Old Town is older than Zanzibar, and other settlements in East Africa where Bantu, Arabic, Persian, Indian, and European influences fused into the Swahili culture. The town, with its relatively well-preserved buildings and traditions, is now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The island’s natural beauty, history, culture, and popularity with tourists, are what led the bar and restaurant’s original owner to situate it right in the Indian Ocean canal that separates the Old Town from Shela, the newer part of the island. The remoteness of the location is perfect. It’s a respectable distance from the conservative Muslim community on the island, and also an alternative for those looking for cheaper food and alcohol than places like Majlis Resort on Manda Island and Peponi Hotel in Shela that serve food and alcohol at a steep price.

The current proprietor, Fridah Njeri, doesn’t have rent costs in the traditional sense. Instead, she pays the Kenya Ports Authority (KPA) and the Kenya Maritime Authority the relevant licences. “It’s exactly like a vessel. When purchasing a yacht, you must pay the KMA and KPA for seaworthiness and moorings, same to the bar,” Njeri proudly said.

A group of tourists posing for a picture inside the floating restaurant in Lamu island, Kenya. Photo Courtesy: Fridah Njogu

In her younger years, Njeri used to frequent the floating restaurant. The establishment first opened its doors to the public in 2007 and was a success until 2012, when a French tourist was kidnapped by the Al-Shabaab extremist group a few kilometres away from it. The tragedy caused a drop in tourist traffic in the area.

Gerald Johnson, the owner then, was frustrated after the incident and wanted to close the business because it had begun to lose money. Njeri, however, resigned from her position with an NGO and purchased the restaurant because she was certain that her business plan would succeed.

“The company was on the verge of collapse, and Gerald wanted to demolish it, but I decided to buy it. I bought it in 2014 for 350,000 shillings (approx. $US2247), but renovations would cost me up to 2 million shillings (approx. $US12, 840),” Njeri recalled.

According to Njeri, the uniqueness of her entertainment spot is the main draw for the majority of her patrons.

A view of the floating restaurant in Lamu island, Kenya. Photo Courtesy: Fridah Njogu

“Many people wonder how the structure stays afloat,” she said.

The structure is supported by about 200 airtight, pressurised plastic drums, each holding 200 litres of water, and the buoyancy created by the wooden structure holds the drums together and keeps the structure afloat. The walls and floor of the construction are made of cinder timber that has been coated in woven reeds. Its thatched roof gives it a rustic appearance.

“Based on the science of pressure and buoyancy of the plastic drums pressed underwater by the weight of the hefty structure sitting atop them, the structure floats,” she added.

According to Njeri, another thing that attracts visitors is their food. The restaurant serves traditional coastal meals. As is customary in Lamu, seafood dominates the menu.

“Visitors can eat prawns that have been dried or stewed, depending on their preference, crab soup, or fish served with ugali or rice and we also serve nyama choma (grilled meat),” she added.

A display of foods served to guests at the floating restaurant in Lamu island, Kenya. Photo Courtesy: Fridah Njogu

Marium Kokani, who has lived most of her life in Lamu, has been coming here since it opened.

“The most interesting thing about the restaurant is that they sell both meals and alcoholic beverages, which is very hard to find in Lamu Island,” she said.

Kokani witnessed the serious toll COVID-19 took on the travel and tourism sector, including the floating bar and restaurant. The numerous restrictions imposed by the national government resulted in a sharp decline in the number of visitors.

“We could not visit the restaurant anymore since the structure had to be moved out of water and this affected us so much since it was the only place we could get drinks and food at an affordable price,” said Kokani.

In 2020, however, Njeri revamped the building in anticipation of the end of the pandemic. It cost her 3.5 million shillings (approx. $US22,471). The structure had to be removed from its moorings and hauled off the ocean in order to undergo extensive repairs, which took two months.

“If this was on land, I could get a title deed worth 100 million shillings to help me do what I wanted. Because you can receive up to 300 million with land in Lamu as collateral, but this is currently in the midst of the sea, making it harder to get collateral,” Njeri shared.

Despite the financial and emotional strain, the reopening of the floating structure coincided with the launch of the Lamu Port in 2021, which meant an increasing number of customers for Njeri.

“Structures such as the floating restaurant in Lamu is one thing that many people do not expect to find everywhere. They can preserve the culture through their food, the structure itself and its location. This has been able to greatly boost the Lamu economy,” Aisha Abdalla Miraj, the County Executive Committee Member (C.E.C.M) for Tourism, Culture, Trade and Investment in Lamu County, said.

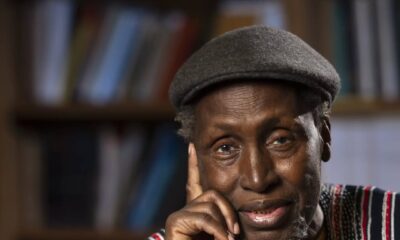

Fridah Njogu (third from left) posing for a photo with tourists at the floating restaurant in Lamu island, Kenya. Photo Courtesy: Fridah Njogu

Frida Njeri, now also the Vice Chair of the Lamu Tourism Association, has a new strategy for her swaying restaurant. She intends to add a conference centre facility and extend two more platforms: one reserved especially for restaurant reservations and the other for lodging.

“I intend to make it a safe haven for all entertainment lovers,” she concluded.

Story Credit: Velma Pamela for Bird Story Agency