Features

BN Prose: Puppet by Blessing Christopher

I’m going to die soon, he thinks. He is not ill as far as he can tell. The heart attack has not returned because he does the right things: exercise, and eat all the nasty and tasteless things his wife orders the chef to prepare. Like most losers the heart attack might be waiting to strike a second time. He has to live, not so much for himself, but for the people he had pledged his life to.

I’m going to die soon, he thinks. He is not ill as far as he can tell. The heart attack has not returned because he does the right things: exercise, and eat all the nasty and tasteless things his wife orders the chef to prepare. Like most losers the heart attack might be waiting to strike a second time. He has to live, not so much for himself, but for the people he had pledged his life to.

After the first heart attack when he had lain in a hospital struggling to live, eager to return to his life, his wife had sauntered into the ICU in her new sophisticated way. Her walk wasn’t the only new thing about her. He’d stare at her whenever he thought she was unaware of the gaze. He’d search for the old Scarlet beneath the stranger. He realised that the change that power brings is not limited to the power holder. Power, he surmised, is like a pebble hitting a body of water, creating rings of ripples, spreading, altering the calmness of the surface, circle after circle, person after person.

“You’re going to stay here till your treatment is done,” Scarlet had said to him in the hospital. “You think the country is waiting for you? For avoidance of doubt you could just die right now and see how fast we all move on.” Her tone was brisk and crisp like a sharp cut with a sturdy machete.

I’m going to die, he thinks. The thought of death does not displease him. Am I looking for a way out? He wonders. Through death he’d find an escape. He wonders if wanting an exit makes him a coward. For him the search for an exit is beyond cowardice; it goes farther than his desire for an honourable discharge of sorts. Something, a deadly weight is floating over his head, not quite settling on his shoulders, hovering and waiting to drop and extinguish him. The floating weight expels the air around him, leaving him gasping, not really breathless, but with a threat of total expulsion of ventilation. He sits in the high-backed chair and wonders whether what he feels is a premonition. It cannot be. Premonitions entail vision, and he had been accused of being visionless by the media.

He leans towards his wife. Her perfectly made-up face fibs about her true age and it startles him that they – Scarlet and him – have become experts at deception. Her deception is more costly than mine, he thinks. Hers cost money to maintain with her army of make-up people and stylists. Mine might only just cost my life. Scarlet is wearing a red gele, a yellow blouse and a red wrapper. Red and yellow represent their blood and freedom, the colours of their nation.

“Someone is watching me,” he says to his wife.

Scarlet does not stir in her seat, but her eyes comb the area to make certain no one heard the words.

“You are talking crazy again, Joseph,” she says, Smiling, just in case anyone wonders at the topic of their conversation. She wants onlookers to think it is light, inconsequential, couple banter.

“It’s true,” he affirms.

“Yes, it’s true. Fifty thousand odd people are watching you right now. One hundred million more are watching in front of their TVs at home.” She turns away, letting the ghost of the forced smile linger for the hungry cameras.

“Stop being paranoid,” Scarlet adds discreetly. The words force their way through her closed, smiling lips, like a ventriloquist’s “The many people watching you don’t need to start wondering about the state of their President’s mind.”

And people are watching him. She is right. In the tsunami of eyes, he feels like two are trained specifically on him, intentionally on him. The eyes had come to do a job. Maybe the eyes will kill me here in freedom square before the whole world, he thinks. He remembers the saying that just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.

Freedom square is packed full of his fellow country people who had braved the July heat and the violent threat of rain in the air to wish their country a happy seventieth birthday. Their independence had been received in freedom square seventy years before. Old photographs of that historic day show two representatives of the Crown handing over a flag to the country’s first Prime Minister as the union jack flew low in the background. For sixty-nine years the ceremony has been marked in the square, now a small stadium, with seats for fifty-thousand.

The Master of Ceremonies calls the president to the podium to give the anniversary speech. The president walks to the podium, head held high, smiling. Eyes please don’t kill me now, at least not in the middle of my speech, he implores. He had written the speech himself. On paper he had described the country as a seventy-year-old sleeping giant, hibernating, waiting to be roused, about to be roused. He wonders how he had not died of laughter when he’d penned the words. Any seventy-year-old person or thing should be wise and senile like his grandmother had been at that age. The old woman used to sit on her low stool and inhale lines of snuff while cursing her progeny for their dullness, then with glassy eyes induced by the sting of potent tobacco, would regale her family with wisdom characteristic of someone who had lived so long and so full and so well.

The president remembers being tormented by Okon, the village madman. There was a legend that the madman’s brain had been parboiled from smoking too much ikong ekpo thereby forever altering his destiny. The madman would wait outside the primary school fence made with dried bamboo. The madman would chase, catch, and beat him Joe, dirtying his white uniform shorts and shirt.

His grandmother would wrinkle her nose at him when he returned from school.

“Well, you sure smell like a madman now,” she used to say, grinning.

When the boy missed school for two days, his grandmother called him.

“You can’t stop going to school because Okon wants you to. What will you do when he brings the fight to your house? And he will.”

“What should I do?”

“Be mad. Be madder.”

Okon waited outside the fence as usual for skinny, knock-kneed Joe. Joe, on spotting Okon, tore off his uniform shirt, yelping like a wounded dog. He waved the torn shirt over his head like a shipwrecked sailor, eyes flashing maniacally, the scream rising in decibel as he got closer to the madman.

The madman sighted trouble and retreated, wondering when Donatus Olo’s son had gone mad. An old illiterate woman had schooled Joe on détente and mutual assured destruction long before the cold war made the concepts popular.

His grandmother wasn’t impressed by the victory.

“But did you have to tear your only school shirt? Now we can judge how smart, or not, your mother really is by her offspring. My son could have done better.”

Joe didn’t tell his grandmother that he was her progeny as well. Even as a young boy he knew something of diplomacy.

He thinks that the country at seventy is a comatose woman-child that had fallen on her head at infancy and had been forced into a permanent vegetative state.

He does not say that. He reads his speech of greatness coming at them like a meteor, greatness that would hit and stun and transform. Their very own big bang.

He clears his throat and reads the printed words: We are on the edge…

He remembers when his dreams – this nightmare – had been set in motion.

He had struggled to accommodate the fact that Zanedi was sitting in his sitting room. The Zanedi, a statesman as someone of his ilk was known. Statesman because he had ruled the country in the past and was still very relevant politically, statesman because calling him a kingmaker was not polite.

Joe had sat in his own sitting room and tried to look at it through Zanedi’s eyes. The diplomas lining the walls, a dusty bookshelf pushed against the wall to make way for the artefacts masquerading as electronic appliances all made Professor Joseph Olo claustrophobic. He felt ordinary. He didn’t know many people who aspired to ordinariness. He was at that moment being teased with a proposition many would have sold their souls for.

He continued reading:

…We have been propelled to this symbolic point with the help of our heroes past, men and women whose blood fertilized the soil from which our freedom grew.

“What do you want me to say?” he had asked Zanedi. The proposition was too strange, too unbelievable.

“It is rather simple, Professor,” Zanedi said. “Say yes.”

We didn’t let their efforts go to waste. We didn’t stand still. We kept moving through our wilderness.

“I know the question you’re going to ask next professor.” Zanedi said, scratching the snow-white tufts of hair on his head.

“Why?” Joseph asked anyway.

“Because you’re a good man, Joseph, and you deserve it. This country deserves you as president. We need good men.

Through sixty-nine years of mistakes and rife, we have finally arrived on the edge of a wave of change and incredible growth.

“So what do you say, Professor?”

We will take our place in the world as giants of Africa and as the underestimated champions of the universe.

The president tilts his body to the left. He eyes another corner of freedom square while holding on to his wife’s image in the corner of his eyes. Her yellow blouse will soon be redecorated with my blood or chunks of my brain matter depending on where the bullet will hit, like Jackie Kennedy, he thinks.

It was in freedom square the president had taken his oath of office. Left hand on a Bible, right hand raised, “I, Joseph Olo… His wife had stood there, here, watching him with an incredulous smile.

They had sex in the master bedroom of power mansion immediately after the president was sworn in. The bedroom alone was larger than the house he had built and planned to retire in. His wife had said “your excellency” playfully, when he’d sagged, sated, on top of her. They hadn’t done anything since her menopause years before, but there he was, sixty-seven years old and having sex with his wife like when he’d been younger. Power. The vagaries of power, he thinks, Power as a fetish, power as a stimulant and love-awakener, power as a load of sperm heady for release.

He’d developed the vice later. He thinks of it as occupational hazard. Securing women for the president was a real job, he learnt. But he realized quickly that whoever held the post wasn’t good at his job. The women were always the same: very tall, very light-skinned, and very ambitious. He didn’t complain about the lack of variety, but it didn’t make sense to him, the sameness. Why combat monotony with monotony?

We are here now, to stand unified as we welcome our respite. We will stun the world with our resources, human and material.

He feels like the watching eyes have shifted, the heat focused on another part of his body; head or heart? Where will I be struck?

His vices, he’d lie under them as they rode him, breasts swinging, hips raised and lowered on his, impaled by his Viagra-sponsored hardness. They’d see him lying there, hands behind his head, seemingly in surrender, and then they’d move, always, to wrest power from him with expert grinding and twerking and not looking anywhere else but his eyes. They always expected total surrender.

As it was in sex, so was it in real life.

People like using me, he thinks.

We are here

Am I so useable? Am I easily plied, am I pliant, does my pliability show?

He flips the next page of the speech, trying to steer his mind from the murk it had waded into. His mind doesn’t cooperate. It veers off into aspects of his life he doesn’t remember, or care to remember, like a dying man with his life playing out in a loop in the final seconds before he departs for good.

He had said yes to an easy presidency. There was an expectation that all answers demanded by his sponsors would always be in the affirmative.

He’d said no. Repeatedly.

The current no, the billions of Dollars worth of ammunitions no, had started a series of events preceded by an impeachment notice, a threat really, since people didn’t dispose of good men so mildly. Good man was a synonym for weak man, and he knew it.

No to arms deals made prosperous by internal conflict carefully stoked by the people who had installed him in office as someone who would lead and look away and write beautiful speeches. Someone mute. But he’s refused to play and had threatened to talk. You can’t say no when yes had gotten you the highest office in the land. It is not the nature of the puppet to tug on the strings supporting him, choreographing him.

Today with arms lifted high we welcome change!

The square erupts in ferocious applause. The president waves to all the corners of freedom square. He can see his wife smiling in the periphery of his vision. He lingers.

I am asking for it, he thinks.

The eyes, two sharp points of light and anger, follow the president’s every move.

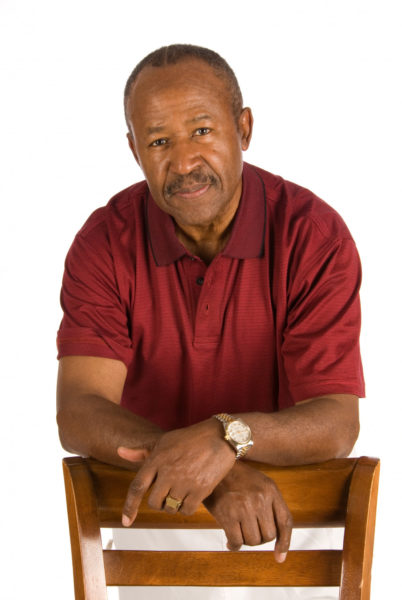

Photo Credit: Dreamstime | Sophie Davis