Features

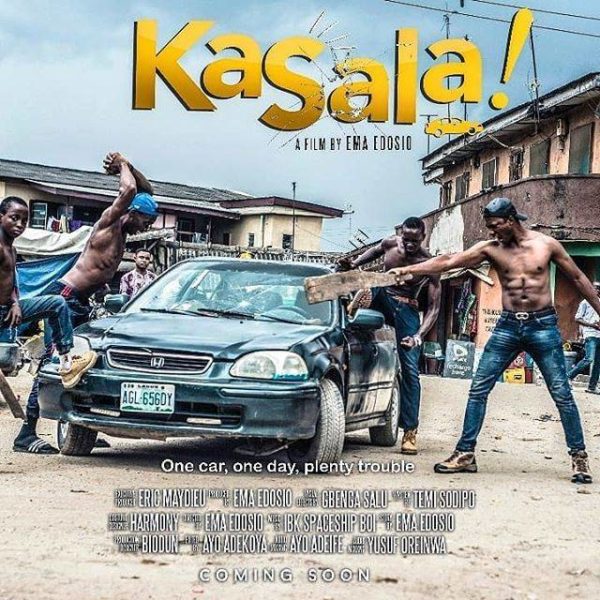

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: Ema Edosio Gets a Nigerian Boy’s Life Right in Kasala!

2018 has not been a very good year for Nollywood. It is almost June and the industry has not produced an Ojukokoro, a ’76, and certainly no Confusion Na Wa. Viewers are yet to see anything that has a filmmaker’s artistic vision stamped across the duration of a film. What we have had instead are the incoherent comedy of Toyin Aimakhu and the glitzy faddishness of Mo Abudu. But Kasala, directed by Ema Edosio and yet to reach cinemas, might yet save the year.

2018 has not been a very good year for Nollywood. It is almost June and the industry has not produced an Ojukokoro, a ’76, and certainly no Confusion Na Wa. Viewers are yet to see anything that has a filmmaker’s artistic vision stamped across the duration of a film. What we have had instead are the incoherent comedy of Toyin Aimakhu and the glitzy faddishness of Mo Abudu. But Kasala, directed by Ema Edosio and yet to reach cinemas, might yet save the year.

The film takes place within a day and follows four boys living in mainland Lagos. We are introduced to them the morning of a party they plan to attend, their cramped apartment, petty squabbles and meagre living a contrast to what joys this party might bring. Everybody loves a party but if you lived where they live you too would seek momentary escape.

To enter in style, TJ gets the bright idea to steal his uncle Taju’s car. And so it goes: the party is swell, the plan goes well—until Abraham, who has asked to drive on the way to the party, surreptitiously dispossesses TJ of the car keys. This theft is the film’s pivotal action and is one of many moments Edosio’s film shows an understanding of the average male friendship: of how mischief and good intentions between boys are frequently and necessarily entwined. Abraham crashes the car in an unconvincing scene: It is not very clear how the scar at the centre of the windshield has come to be. Nonetheless the boys now have to find a way to fix the car before Brother Taju returns from his job at the butchery.

While the boys come up with several ideas on how to fix the car, Brother Taju is himself having a torrid time. He tries some hide-and-seek with both his employer and the local Shylock he owes money but the goons sent by the latter (played by Jide Kosoko) are alert to his tricks. In one scene, he visits a friend owing him but the guy runs into his house, shuts the door, and he has to carry out a desperately hilarious conversation through a window. Fact is: the film’s adults in Kasala are just as beleaguered as the kids and remarkably both the boys and the adults are treated without condescension. It would be easy and cheap to make out the kids as heart-of-gold heroes and the adults as opposite but that would be too cheap. Instead we get genuine some progressive suspense. Will the boys succeed? If they don’t, how do they face Brother Taju?

Edosio juggles all of the strands of her story admirably, her major achievement being the film’s pacing. After one set-piece ends, before long there is another and then another, all of which she stitches together with some of the deftest editing in recent Nollywood history. For an industry notoriously prone to misjudging pace, Kasala feels like a novelty.

Of course in cinema of this kind, technical mastery is nothing without the story which itself is nothing without good casting. And while it might be due to a low budget, the use of entirely unknown faces to play all four boys feels like a production masterstroke. These young actors don’t have the burden of previous acting history and so it seems like they have been life-long friends who we have just happened on at this time in their lives. Many times their dialogue is so natural it feels improvisational, not in terms of sloppiness, but in how inevitably one line leads to the next. The script conveys one of the basic rules of friendship at this level: merciless mocking and the acceptance of it is sometimes the ultimate display of affection. The one perhaps avoidable trap of the ease and high verisimilitude of Kasala’s dialogue turns up in a revelation of sexual abuse suffered by one of the boys. It is brought up and dismissed. I came to think of it as a missed opportunity to present the group of boys—and the film itself, with a more substantial emotional centre.

Still, Kasala’s true subject is the life of boys wanting to be men. It should be seen by young Nigerians, many of whom have not yet had the opportunity of seeing themselves on the big screen doing recognisably young Nigerian things. But then again, everyone should see Kasala when they get the chance, not just because it tells a truly Nigerian story with believable characters, but also because it is very good fun.