Features

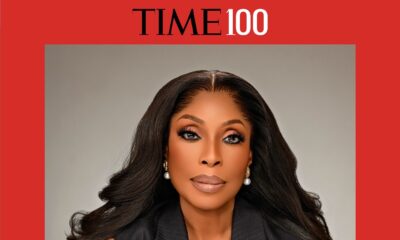

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: Mo Abudu As Nollywood’s Saviour?

Mo Abudu has become unavoidable in Nollywood. If you work within the industry, she’s inescapable. If, like me, you work outside of it, you have to deal with her products. She is, in a sense, bringing the studio system of 1920s-1960s America to Nollywood, and we might come to think of her in the way Hollywood historians think of Louis B. Mayer. If, as they say, Mayer’s view of America became America’s view of itself, it is conceivable that Nigerians might come to view the flamboyant upper class in the way Abudu’s pictures have shown them. Almost single handedly, Ms Abudu has turned Nollywood into a content farm for luxury cinema.

Mo Abudu has become unavoidable in Nollywood. If you work within the industry, she’s inescapable. If, like me, you work outside of it, you have to deal with her products. She is, in a sense, bringing the studio system of 1920s-1960s America to Nollywood, and we might come to think of her in the way Hollywood historians think of Louis B. Mayer. If, as they say, Mayer’s view of America became America’s view of itself, it is conceivable that Nigerians might come to view the flamboyant upper class in the way Abudu’s pictures have shown them. Almost single handedly, Ms Abudu has turned Nollywood into a content farm for luxury cinema.

A number of directors and screenwriters might admit to an awareness of the danger to diverse artistry her money and reach appear to represent, but apparently it is impossible to expressly decline her gifts. The result is that any random list of filmmaking persons Abudu has worked with in some way is a trusty roster of New Nollywood talent. Niyi Akinmolayan, Ishaya Bako, Daniel Oriahi Naz Onuzo, Tope Oshin and others have bowed before her naira.

Of itself this is nothing harmful. As someone once said when an artist meets a rich person, the latter should part with money for the talent of the former. The trouble here is that each time any of these persons have worked on Mo Abudu’s curated tales they have almost certainly abandoned their own vision. And because Abudu’s stories are really truncated episodes of one long tale of haute-couture narrative, the result depletes the kinds of stories Nollywood has told.

Now this is perhaps not so much a significant loss in the case of some of these filmmakers whose own work leaves much to be desired. But that is hardly the case with Oriahi, Oshin and Bako, three very promising directors currently working in Nollywood.

Oriahi came on with the strange, psychologically ambitious Misfit. He then made Taxi Driver, which borrowed title and some themes from Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film, a detail suggestive of his film knowledge. I didn’t care for his last film, Date Night, but even there the idea shimmered with promise. And each time Oriahi works away from the big screen, ostensibly, understandably, for income, there is a question that arises: What ambitious cinematic stories would he tell had he the required funds?

Oshin made In Line, supreme candidate for the best-film-no-one-saw award last year. The film subverted the noisy ethos of Nollywood by using silence in keys scenes. The performances were just as spare, lacking the melodrama Nollywood seems to associate with import. Unfortunately Oshin’s follow-up, New Money, was indicative of how Nollywood fails its talents: Oshin made one good film nobody saw, then a poor one film which many saw. That a filmmaker who did In Line only months later had to make New Money tells its own tragedy, but we’ll wait for her next personal project.

With Bako, it is almost forgettable that he directed the 2012 documentary Fuelling Poverty, which caused some controversy. His entry to Nollywood has seen him service the production egos of Genevieve Nnaji and Abudu. The edge to his work which got him the attention of the government all of those years ago has gone missing, replaced as it is with celebrity, colour and a semi-insipid wholesomeness in Abudu’s Royal Hibiscus Hotel. He fared better with Nnaji’s Road to Yesterday. It would be interesting to see Bako write and direct a film about what it means to be young in Nigeria, a bit like what Ema Edosio achieved with Kasala, but that seems a pipe dream as his mercenary phase lingers.

And yet for all of these errors of big budget commissions, for which Mo Abudu is only symbol and not omnipresent source, news of the Ebony Life working to adapt Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman is reason for a reversal of expectations. Perhaps she has arrived at the point the guys running DC Films came to recently.

“Somebody once said the best business strategy in motion pictures in quality,” said Toby Emmerich of Warner Brothers, which owns DC. “And I think in a world of Rotten Tomatoes and social media, what’s been proven [is] the better the movie—particularly in the superhero genre—the better it performs.”

Ordinarily this should be self-evident but nothing gets in the way of great filmmaking like a bid budget for publicity. And publicity is Abudu’s major asset, but it is hoped that the adaptation of Soyinka’s tricky play signals some intention in the realm of thoughtfulness. After all, to my mind, the work from Soyinka’s oeuvre that would best work with the Abudu aesthetic is a modernisation of his popular play The Lion and the Jewel. If you have read the play, it should be easy to see how that it plays out with Abudu’s love of chic colours. She could also call on any of the greying men of The Wedding Party to play Baroka and use any of the Ebony Life starlets as Sidi. But apparently Tunde Kelani is working on an adaptation of that play.

For the Death and the King’s Horseman adaptation, Abudu’s penchant for happy, colourful endings will go on vacation if it’s faithful, which it has to be given the importance of the fates of the protagonist Elesin Oba and his son Olunde. Will it be modernised wholly? Would the film stick to Soyinka’s setting? How will the Nobel laureate’s over-poeticisation of dialogue, of language, be transmitted onscreen for today’s movie audience? The decisions made by Abudu and her handpicked director should make for interesting viewing.

In private conversation, some Nollywood filmmakers agree that Abudu has the means to do something artistic, something risky, something different from the Hollywood-lite fare she plies her viewers with. Who but someone who made so much money on one comedy and its not very imaginative sequel can afford a bit of a risk on a cinematic product that should curry some critical prestige?

Of course it could also be that her past commercial success means Ms Abudu might think only to continue on the path of chic-lacklustre art for the most profit. But we can hope that in the hands of those with money and media might, power will be used for ambitious work at some point. I mean: if at this point we can’t expect more from a Mo Abudu, what chance really does New Nollywood have?