Features

Niyi Ademoroti: Is Nollywood Ready to Tell the Stories of Modern Nigerian Women?

These prophets, besides being from white garment churches, have something in common: their dubiousness is made apparent. In Life As It Is, you hear the prophet go, “Ligaligali,” a popular refrain from an old fuji song. In Skinny Girl in Transit, the prophet dances while singing, “Lori le o di gobe.” Man of Her Dreams has the prophet bouncing comically on foot, chanting “Angel Uriel.”

It’s the golden age of the Nigerian culture. Our films are premiering in foreign film festivals; our filmmakers are signing major deals with streaming behemoths; and our musicians are being profiled in international music journals. Not wanting to be like the Ijapa who abandons the feast in his own home and imposes himself instead on his neighbour Aja, I asked that a friend recommend to me a web series. That’s how I discovered Life As It Is.

It’s the golden age of the Nigerian culture. Our films are premiering in foreign film festivals; our filmmakers are signing major deals with streaming behemoths; and our musicians are being profiled in international music journals. Not wanting to be like the Ijapa who abandons the feast in his own home and imposes himself instead on his neighbour Aja, I asked that a friend recommend to me a web series. That’s how I discovered Life As It Is.

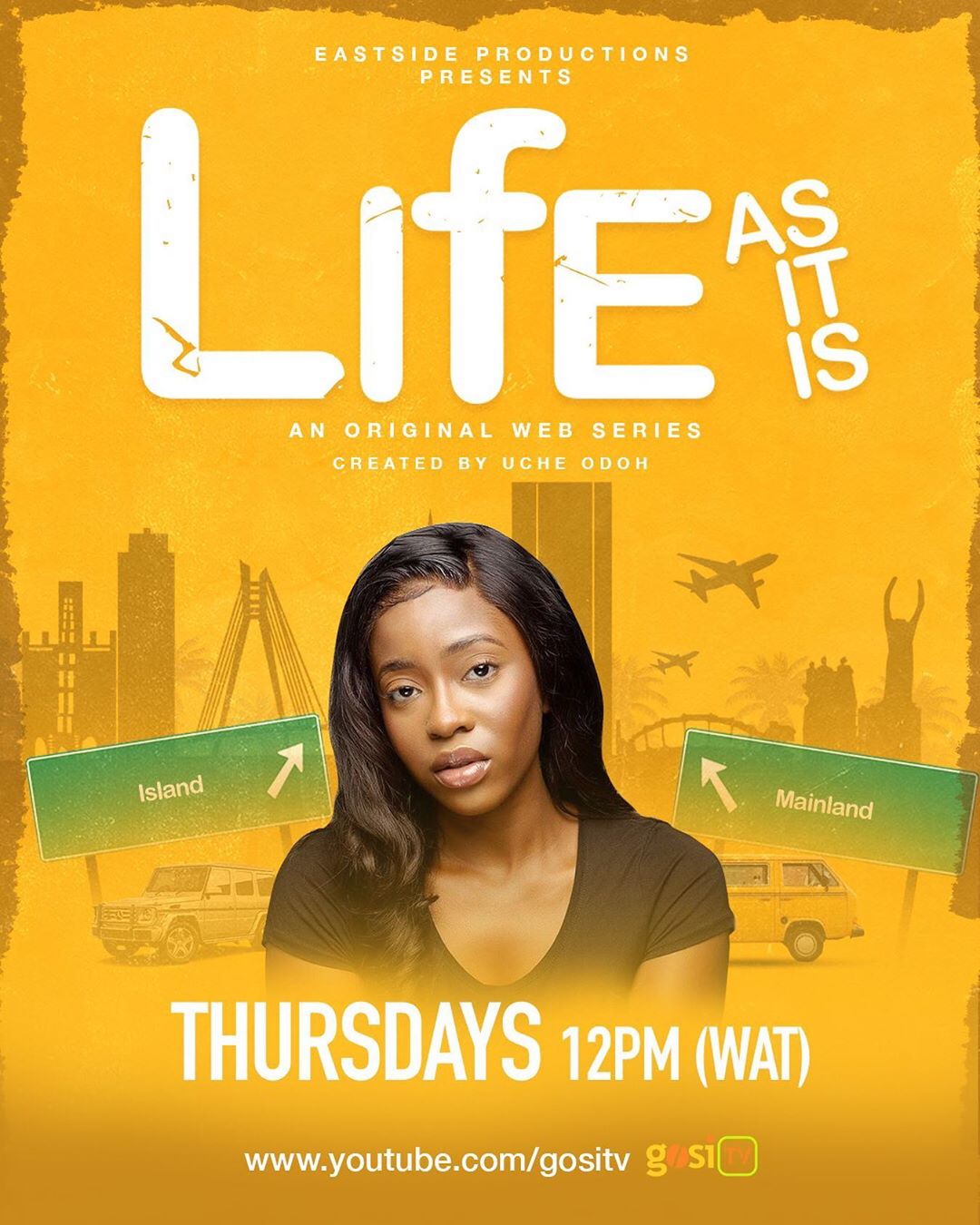

Life As It Is, directed by Uche Odoh for Gosi TV, opens to Nara (Shalewa Ashafa) folding her clothes into a bag and soliloquising about her moving out of her mother’s home. We soon find out why: her mother (Uche Mac-Auley) walks into the room, a white-garment prophet (Lateef Oladimeji) in tow. The prophet rings his bell, skabashes, from a bottle sprays water around the room generously. Nara fails to understand and looks to her mother for some clarity, but the older woman shushes her.

Religion holds a curious premium over the lives of Nigerians, we all know that. It has pervaded the quotidian so much so that our movies continue to end with the tagline “To God Be the Glory.” Nothing out of the ordinary if a show, expected to reflect reality, presents something that isn’t out of the ordinary in our daily lives. But is it, really, not out of the ordinary, in Nigeria, to invite a prophet into your home to pray for your daughter who happens to be on the cusp of adulthood?

Man of Her Dreams, another web series, this one created by Victor Sanchez Aghahowa for BukaFedGeeks, bears certain similarities with Life As It Is. There’s the middle-class daughter and mother. An absent father. A single protagonist just starting out adulthood. And, most importantly, at least for the sake of this essay, a mother who believes in the prayers of a prophet and its power to fill a perceived void in the life of her daughter.

While the perceived void in the case of Life As It Is and Man of Her Dreams are encompassing (think of all the problems a new adult faces – there’s relationship drama, but there’s also job wahala, questionable alliances, and a gutsy disregard for the boundaries of freedom established by parents), that of Skinny Girl in Transit (another featuring a middle-class family with a mostly absent father) is singular: relationship drama.

Skinny Girl in Transit, created by Temilola Akinmuda for Ndani TV, is the most watched web series in the country. In it, we find a melodramatic mother (Ngozi Nwosu) who invites a prophet (Woli Arole) into her home to cast out whatever spirit is stopping her daughters Tiwa (Abimbola Craig) and Shalewa (Sharon Ooja) from finding men.

These prophets, besides being from white garment churches, have something in common: their dubiousness is made apparent. In Life As It Is, you hear the prophet go, “Ligaligali,” a popular refrain from an old fuji song. In Skinny Girl in Transit, the prophet dances while singing, “Lori le o di gobe.” Man of Her Dreams has the prophet bouncing comically on foot, chanting “Angel Uriel.” In all three, the daughters make clear their distrust for the prophets. They ask their mothers, “Mummy, what is this?” But the mothers remain oblivious. All of it births the internal debate: are these attempts at satirising what the writers believe is an actual middle-class phenomenon, or do they fail, due to an attempt at comic relief, to communicate a troubling Nigerian reality.

Noticing this pattern (of mothers and prophets), I turned to my friend, the same one who recommended Life As It Is, and asked if it was a Nigerian reality: this web series staple of women inviting white garment prophets (not just any pastors) to pray for their daughters. While we’d both heard of parents visiting pastors, prophets and alfas to pray for their kids; visit these same people with names of their kids and their suitors; and inquire about the destinies of their kids – we realised we’d actually never heard of mothers bringing prophets into their home.

The Men’s Club, directed by Tola Odunsi for RedTV, is one of the few shows that attempt at exhibiting male millennial Nigerian lives. All four men who make up the “club” – Lanre (Etim Effiong), Tayo (Efa Iwara), Louis (Baaj Adebule), and Aminu (Ayoola Ayolola) – have lives rife with relationship issues. Yet, in situations where parents are in the picture, there exist no pastors or prophets. In Lagos Big Boy, too, directed by Dare Olaitan for Ndani TV, where four men turbulently navigate the expectations and trials of being a Lagos big boy, no prophet is in sight.

Obviously, the difference in volume between shows that portray female adult lives and male adult lives is indicative of which is believed to be more entertaining. More significant, however, are the ways in which these lives are portrayed.

Conversations with even more friends revealed that no one had ever witnessed or heard (and we know gist does get around) of mothers and prophets, not in the ways these shows insist on projecting. And while women certainly get the brunt of the “When are you getting married” hassling, and much earlier too, men too are asked to present suitresses. Besides, financial independence is demanded of men at this same stage, or even earlier, which also justifies—at least to Nigerian parents—the need for prayers.

There are questions to be asked: about why we continue to represent women in a certain light that might not honestly reflect reality, and why men don’t get represented in that light. If both men and women are prayed for (think fervently, in Nigerian terms), why then do we only see it in our arts in the lives of women? Sure, it is indicative of a poverty of ideas – this not-exact copy of our real lives that makes into easy comedy, the kind Nigerians can’t get enough of. However, that this reality continues to be gendered, by female writers, nonetheless, points to something more.

Nigerian women today have found the courage to stray from every norm. A casual scroll through Twitter and you’ll find discussing career, finance, women’s rights and feminism, travel, complicated but ultimately loving relationships with their folks. Their lives are full and free. Marriage, or their parents’ want for it, is hardly the locus. To continue to tell these age-old stories as seen in ancient flicks, indicates that maybe the new skins in Nollywood today, try as they might to give the impression of modernity, are still just filled with old wine, and are not ready for the modern Nigerian woman.