Features

Franklin Ugobude: Mon Ami Fela – Viewing Fela’s Life Through a Different Lens

Fela challenged the entire moral basis of society. This was a man who, in 1977, released an album called Zombie, a metaphor used to describe the methods of the military government. Like the song says, “zombie no go talk unless you ask am to talk, zombie no go move unless you tell am to move”.

It’s a late evening in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso where FESPACO – the Pan African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou is scheduled to hold. The festival, which holds once every two years, is the largest film festival on the continent, gathering filmmakers and film lovers all over the continent for a week of an African cinema experience. One of the most fascinating films on the program for this week-long event is Mon Ami Fela (My Friend Fela), a film about the late Nigerian icon, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. The ninety-two-minute documentary by Brazilian director, Joel Zito Araujo, looks at the life of the musical genius, Fela, from an entirely new narrative – one that isn’t brought to the limelight as often as it should be: his political activism.

It’s a late evening in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso where FESPACO – the Pan African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou is scheduled to hold. The festival, which holds once every two years, is the largest film festival on the continent, gathering filmmakers and film lovers all over the continent for a week of an African cinema experience. One of the most fascinating films on the program for this week-long event is Mon Ami Fela (My Friend Fela), a film about the late Nigerian icon, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. The ninety-two-minute documentary by Brazilian director, Joel Zito Araujo, looks at the life of the musical genius, Fela, from an entirely new narrative – one that isn’t brought to the limelight as often as it should be: his political activism.

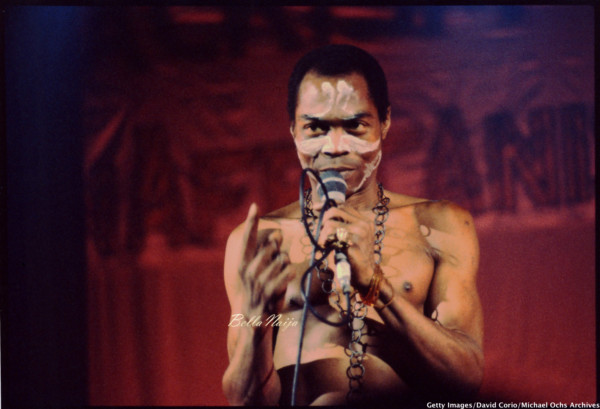

Fela Anikulapo-Kuti is regarded mostly as a musical icon; one who is in death, still relevant as his music lives on. No matter the occasion, his lyrics have such evergreen quality and an all-encompassing content, such that even at a party, lyrics such as ‘I sorry sorry oh, I sorry for Nigeria..’ will still get people gyrating or starting conversations. He is also credited with coining and creating Afrobeat, a genre that has grown in popularity worldwide.

Homegrown musicians like Wizkid, Davido, Bixiga 70, Abayomy and Mr Eazi are prime examples of artists who have emerged on the global scale, all thanks to Afrobeat. Apart from his musical influences, Fela has been credited with influencing the fashion sense of some artists; some of whom have gone from adorning Ankara and beads to just underwear. In all of these, Fela is often portrayed as an eccentric African pop idol of the ghetto. However, he was a strong political leader and that part of him is what this documentary showcases.

It kicks off with the song ‘Why Black Man Dey Suffer’ from his 1971 album of the same name, and goes on to use some of his other songs throughout the film. We’re introduced to Carlos Moore, Fela’s friend, who takes us on the journey to unraveling his other side. Carlos is an African-Cuban intellectual who is responsible for Fela’s biography called Fela: This Bitch of a Life. We then go around to meet interesting people who were important to Fela’s life – like his son, Seun Kuti; fellow musicians and co-workers, Ray Lema and Ray Allen, Sandra Izsadore – his lover and friend, as well as Najite Mukoro – one of his wives. The icing on the cake has to be the interview with Lemi Ghariokwu and Babatunde Banjoko, two artists who have, in the past, worked with Fela and created some of his album arts.

There are a lot of interesting ‘truths’ revealed in this documentary. According to Sandra Izsadore, Fela had not always been an activist through his music. She claims he was singing about soup when she met him at an event in Los Angeles. This led to a conversation between them, with Sandra introducing him to the Black Panther Party and giving him books to read. At this time, black people in Africa were marginalized and felt inferior due to the colour of their skin. This interaction would go on to influence Fela’s music and political views. In a later scene, you’ll see Fela, who speaks on this, saying that music is for enjoyment, but the idea of your environment has to be represented in your music, lending credence to his activism through music.

Aside from the fact that Mon Ami Fela tells a compelling story that reveals the glories and tragedies that shaped Fela’s life, it links these stories to the pan-African generation – an act which Araujo says was intentional. Not only are you taken through all of these, but it’s also almost like a crash course on Pan-Africanism and how the likes of Malcolm X, Maya Angelou, Kwame Nkrumah, and Patrick L.O Lumumba shaped and played a positive role in Fela’s life. With all of this knowledge, one will come to appreciate the effort put in Fela’s music and how he became a voice for the masses.

Fela challenged the entire moral basis of society. This was a man who, in 1977, released an album called Zombie, a metaphor used to describe the methods of the military government. Like the song says, “zombie no go talk unless you ask am to talk, zombie no go move unless you tell am to move”. This album infuriated the government and led to the first attack on Fela’s Kalakuta Republic, which resulted in severe beatings and injuries and burning of the home he and his wives had created. That did not deter Fela at all as he went on to release Shuffering and Shmiling in 1978, and Beasts of No Nation in 1989, to mention but a few. He was an activist at the very core, knowing that his activism came with consequences, but defying the odds and growing stronger with every harassment.

As Carlos Moore said, Fela should not be reduced to being a cultural icon, a ghetto hero or an eccentric persona. With lyrics about corruption and abuse of power and the need for Nigerians to speak up for their rights, Fela was defiant. He was a hero that lived amongst us and defied the odds when he could. And he didn’t just do all of this through music alone, he lived it. Literally.