Features

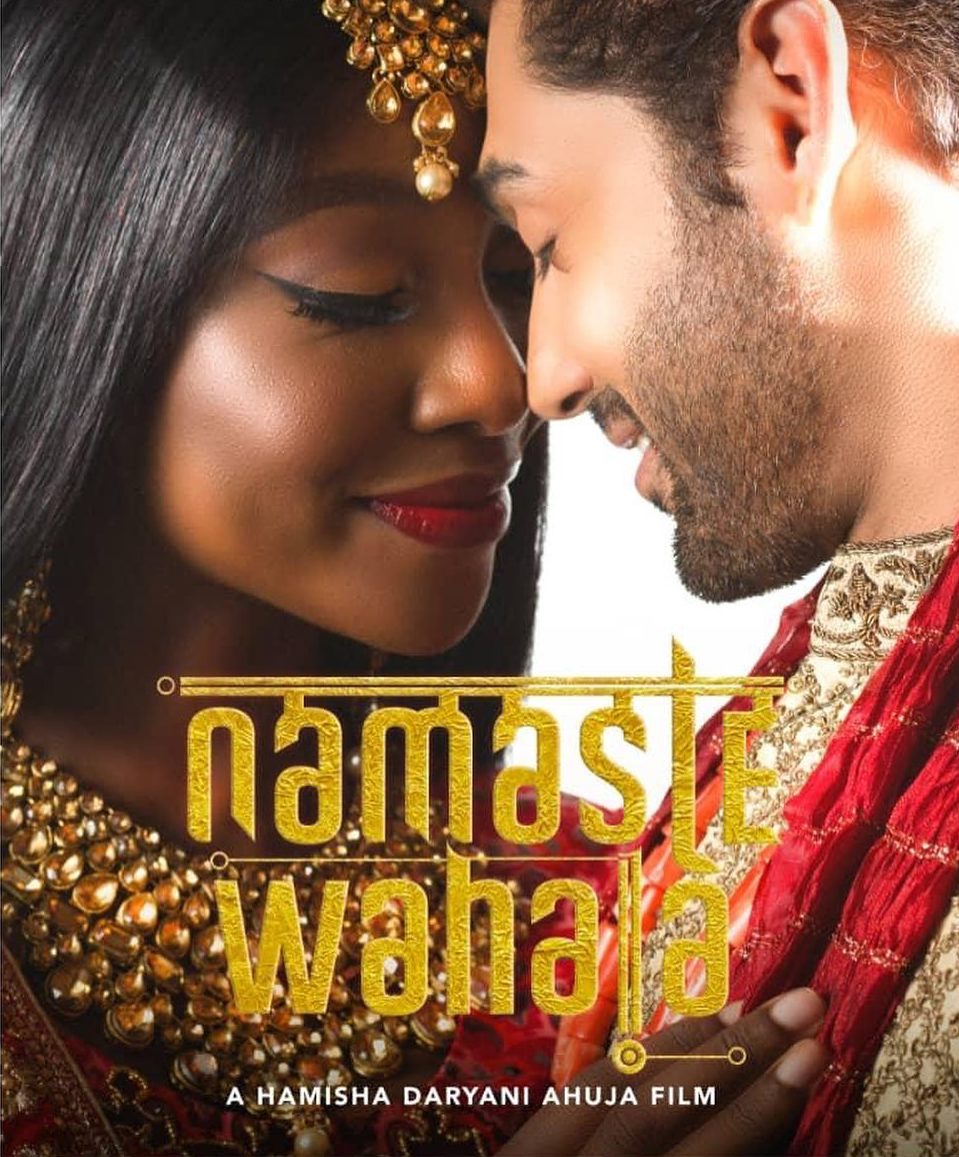

Michael Aromolaran: “Namaste Wahala” Is Betrayed by Poor Execution

It’s never prudent to watch a rom-com on Valentine’s Day when you’re single. Do this and suffer the purgatory of the starving but penniless man seated in a cafeteria, the aroma of exotic fish from nearby diners’ table wiggling a taunting index at his predicament. But when this rom-com is the first offering of a Nolly and Bollywood merger, you have to exile your apprehension to some remote cranny and dig in. That’s what I did. For my curiosity, I was reminded more than once that Coca-Cola is still the best soft drink around – yes, the film is relentless in swinging the eloquent axe of product placement.

Namaste Wahala is a cheesy Indo-Nigerian love story that at least doesn’t take itself seriously. Once, its lead male act quips that he’d have sung for his girlfriend’s father “except we aren’t in a Bollywood movie.” This intended to tease the fourth wall a little apart, but the film from start feels like a film, and never at any point did it resemble plausible reality.

The story is unadorned and straightforward: Indian boy, Raj (Ruslaan Mumtaz) and Nigerian girl, Didi (Ini Dima-Okojie) wish to marry each other but both of their parents stand opposed to it. The plot trope is as old as the Idanre Hill, but that’s not an issue. The problem is the film is sabotaged to stupor by a dowdy execution.

Directed by debut auteur and first-time actor, Hamisha Daryani Ahuja, Namaste Wahala apes the Masala film genre of Indian cinema which originated in the 1970s. Masala films are a confluence of comedy, melodrama, song, dance, and suchlike. As a Nigerian kid, you grew up appending different expectations to several film cultures: Gunfights to American films; Kung-Fu to Chinese flicks; singing and dancing to Indian cinema. Watching Namaste Wahala, however, you get the prickling sense that Raj and Didi’s dancing is only a ham-fisted mimicry of typical Bollywood routines, lacking both competence and élan. The singing, however, is passable, particularly the opening score.

John Updike was obsessed with giving “the mundane its beautiful due.” For Updike, that meant dressing the pedestrian lives of the American Protestant middle class in surreal prose. Nollywood ethos runs in a diametric direction, her recent handouts seemingly bent on the genocide of the Nigerian middle class. EbonyLife is a prominent culprit. Namaste Wahala, a likewise felon. We all know those kind of films – let’s call it “Lekki-wood” – that emphasize life on the good side of Third Mainland Bridge, flashing in immoral detail Nigerian elites caterwauling over things that only rich people can be concerned about, all while speaking English of competing degrees of phonetic correctness.

Broda Shaggi’s cameo is the only representation that the Nigerian middle and lower class would enjoy. Because he’s not rich, he has got to be shirtless and uncouth like the regular NURTW staffer in any Lagos motor park, his tongue firing a thousand unprintables per minute. Broda Shaggi is rude to and insults Raj’s mother, Meera (Sujata Sehgal) for the sake of prying a few laughs out of the watchers. This is not new film practice. Sanyerin, Baba Suwe, and Mr. Latin – all comic actors in Yoruba drama – attained celebrity for their trash-talk talents. Even Shakespeare contrived humour by making his characters get a teensy scat-mouthed. See this excerpt from Two Gentlemen of Verona:

“She hath more hair than wit, and more faults than hairs, and more wealth than faults.”

The above is perhaps also true for Meera, especially when you add that “she hath more racism in her bone than compassion and understanding,” even though the film is too polite to say it.

The film hopes to distract us from Meera’s racism through the cordiality that she lavishes on Emma (Koye Kekere Ekun), a black Nigerian who’s a close friend of her son. If you were to accuse Meera of being a racist, she’d likely respond in that way peculiar to racists the world over: “How can I be racist when my son’s friend, who is like a son to me, is black?”

If it’s any consolation, Didi’s father, Ernest (Richard Mofe-Damijo) is an even more spiteful racist. At least Meera opposes Raj’s marriage to Didi on the grounds that his Nigerian girlfriend cannot conjure jalebi in the kitchen, even if this protest by Meera is only a straw man parry. Ernest doesn’t even deign to provide an explanation. He does a spit-take of disgust and turns to his daughter asking, “You bring me an Indian?”

Character depth is not a strong point on Namaste Wahala. I never understood Preemo’s (Osas Ighodaro) animosity towards Didi. Angie (Anee Icha), Didi’s best friend, is sexually liberal and nothing else. If Emma didn’t exist, we wouldn’t have noticed. He might have been consequential if he’d offered useful advice to Raj on how to win over Didi’s parents.

We also have to question the relevance of M.I. Abaga’s cameo. It’s like that irritating modifier in a piece of writing that ought to have been excised before publication. And although it seemed to matter towards the end when Emma announces to Raj that he has been signed to Chocolate City, a real-life record label owned by M.I. Abaga, one finds it a hardly interesting or credible detail. We never even hear Emma’s songs and have no reason to empathise with his joy.

One other ridiculous thing: Raj exclaims after seeing Emma withdraw money from an ATM. Seeing how sparse the banknotes in Emma’s hands were, it couldn’t have exceeded fifty thousand naira (it’s likely lesser than that figure). Raj asks Emma how he came by such a large amount of money. This is a silly question, and at this point, you just have to roll your eyes at the screenplay. Emma lives in the same top-echelon tenement as Raj in Victoria Island and his rent likely runs into the millions. Surely a little ATM-dispensed cash is not enough to warrant such over-dramatisation.

If Emma got a happy ending, Angie didn’t. Instead, she receives a moral flagellation. “Nobody buys the cow if they can get the milk for free,” Didi’s mother (Joke Silva) exhorts her, an unbidden warning that Angie’s polyandry will eventually reduce her stock. All would be well were this only an instance of drama mimicking real-life sexism. But you get the feeling that it’s the director, Hamisha Daryani Ahuja, who’s really uttering those words, Joke Silva is the puppet by which that directorial ventriloquism is made possible. Needless to say, it’s not the place of art to overtly moralise. Not only does Namaste Wahala deliver artless sermons, but it also perpetuates misogyny with an off-handedness not appropriate for this century.

Ahuja is not a good actor herself. In the scene where her character, Leila, finally meets her mystery admirer, she relishes the revelation with the enthusiasm of one who’s just learned that water is a liquid substance.

Also inserted in Namaste Wahala is a sub-story that has Didi in a legal battle with her father over a client of his who’s guilty of assailing a woman, her client. One, real-life lawyers would cringe while watching those pretensions of legal witticisms. Two, the “battered woman’s” twist is a desperation to lend political gravity to what is only a trivial, skeletal story. The film would be better off if it’d emphasised the racial and cultural nuances, which in real life, would conspire to make Raj and Didi unlikely lovers. In the end, Meera eventually raises the issue of dowry, but it’s a little too late and too fleeting to leave an impact.

Namaste Wahala wouldn’t cause persons who are single to singe with jealous longing as it’s only a tacky hackwork, and it doesn’t matter if said loveless fellows watched it on Valentine’s Day. One should watch the film but only because it’s the first major collaboration between Bolly and Lekki-wood. When you’re done, lock it away and never return to it.