Features

BN Prose: The Cattle Fulani by Oluwadunsin Deinde-Sanya

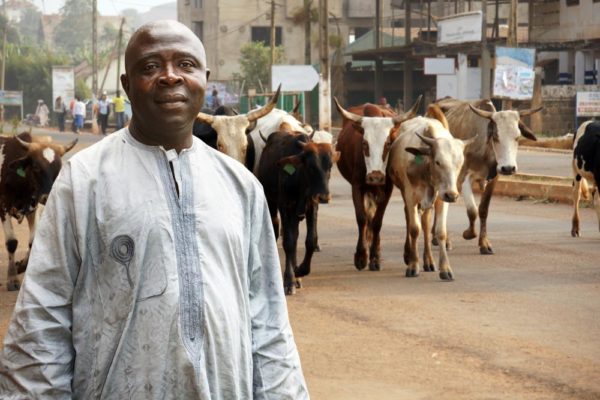

The first time my father’s patience was put to test was when fulani herdsmen raided our village. They had hitherto come often with their cattle marching along like soldiers in parade; their tails hitting their backs frequently as their mouths danced left and right. My siblings and I would sit outside as they passed, taking in the sight with awe. Sometimes, we would throw stones at one of the bulls and run away, scared it might chase us. We would greet Adamu ‘sannu de aiki’ as he walked behind them. Holding a long stick across his shoulder, he would bare his yellow teeth, wave at us and say ‘yowa, nagode’.

The first time my father’s patience was put to test was when fulani herdsmen raided our village. They had hitherto come often with their cattle marching along like soldiers in parade; their tails hitting their backs frequently as their mouths danced left and right. My siblings and I would sit outside as they passed, taking in the sight with awe. Sometimes, we would throw stones at one of the bulls and run away, scared it might chase us. We would greet Adamu ‘sannu de aiki’ as he walked behind them. Holding a long stick across his shoulder, he would bare his yellow teeth, wave at us and say ‘yowa, nagode’.

We liked Adamu; it was he who gave us ‘fura de nunu’ during the new yam festivals. He gave me ghee and said ‘yarinya, your hair go long’, This continued until several years back when the villagers complained that their cattle ate up their crops and stopped them from coming.

A week after, the herdsmen came; not with their cattle, but with machetes and guns. They burnt houses, moving like possessed ‘egungun’ thirsty for blood; their glistened bodies shone with sweat as it flowed down their temples, their eyes revelled in the mad desire to destroy, their voices rose in a singsong manner, like the chants of war as they destroyed farmlands. That night, Kaigama died. It was said that he stayed in front of his house and was beheaded just like that. It wasn’t true, I had seen him go to fight Adamu over his piece of farmland and Adamu had raised his machete which brought down Kaigama’s head. His face glowed as he looked around and bared his yellow teeth, satisfied.

My father fell ill and had taken 14 days to recuperate. He swore aloud at intervals. Then, he brought down his rifle and polished it. He would later take it back and sharpen his machete; but he would take that back also and content himself with swearing loudly while tapping his left foot on the wooden floor. He lamented about how the cows behaved better than the herdsmen, about how it is often said that the Fulani men valued a cow more than a son. He would be seen pacing back and forth and then wash his face in the calabash of water, so we wouldn’t see that tears had strolled down his face. We always knew because his eyes swell day after day, because his already slim frame got thinner, and his shoulder blade got sharper.

It was the same way we knew that Kaigama was his best friend and they had had a big quarrel and my father had vowed never to forgive him… but now Kaigama had joined the dust. Guilt settled heavily in his heart.

I never told my father what Adamu did until 3 months ago when he came to my father and begged for a small portion of his cocoa farm to grow yams. He said his business did not move well and he needed to survive. My father had asked him to come back three days later for a reply.

It was with difficulty that my father told Adamu he couldn’t get the land. The latter had gotten angry, his eyes popped as his veins rose on his forehead like worms ravaging decayed food – a pulse throbbed violently in his right temple and he strode away, hissing words like the rich never helping the poor.

I was scared;for days my sleep was scarred by the face of Adamu, I remembered his machete and the bouncing of Kaigama’s head. I dreaded every arrival of the moon.

It was my father who later brought down Adamu’s head when he came a week later with some others carrying machetes and knives, they had burnt down our cocoa farm and proceeded to our house. My father had sharpened his machete and alerted the police. They arrived when Adamu’s head had fallen alongside two others, while the rest had made good use of their heels.

My father was arrested but later released. He was never the same; when he looked at us his eyes were void. For weeks he washed his hands but they remained soiled. His cheek bones rose higher as his skin gradually shrivelled, and then he kept shrinking until three days ago.

Thunder bolts ran to and fro the sky, when owls hooted in the peak of the night; my father stared without seeing, his mute body lay on his bed, his left hand clutching the right, his machete beside him. When the phoenix sang a dirge; a stricken lament of a lost soul.

* sannu de aiki – well done

* yowa, nagode – oh, thank you

* fura de nunu – fresh cow milk

* yarinya– Lady

* Egungun – masquerade

Photo Credit: Mirage3 | Dreamstime.com