Features

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: Kemi Adetiba’s King of Boys is a Flawed But Ambitious Nollywood Epic

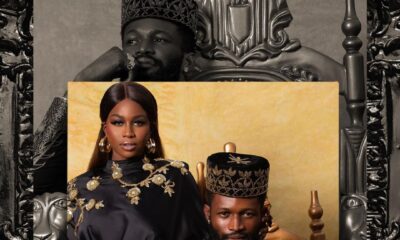

“King of Boys” opens at a party thrown by Eniola Salami (Sola Sobowale). The governor is in attendance, as is the venerated Fuji maestro KWAM 1. This gives the impression that whoever this lady is she is in cahoots with the high and mighty.

“King of Boys” opens at a party thrown by Eniola Salami (Sola Sobowale). The governor is in attendance, as is the venerated Fuji maestro KWAM 1. This gives the impression that whoever this lady is she is in cahoots with the high and mighty.

But the camera shifts to a discussion taking place away from the celebrant. One of the chatting women thinks the lady is despicable but that is no reason to not eat her jollof rice. The other one just wants to dance. This is not the film’s most elegant scene, but it establishes that both ideas of this woman might be true: she is both jolly and dangerous.

At the same party, Eniola, now in what looks like a backroom, uses a hammer on the head of a bloodied man whose real crime we never really learn. As he convulses to death, Eniola wipes her bloodied hand on what must be an expensive wrapper. She then asks her henchmen what they’d eat. You know, because out there in the open, it is a party. The men pretty much shudder at what they have just seen. The viewer might shudder as well, but that would be partly because director Kemi Adetiba is not a subtle director of scenes or a subdued creator of character. Then again, if Lagos is famously not subtle, Adetiba might be its representative director. We later learn that Eniola is the eponymous King of Boys. She sits at the head of a table of gang-lords, and whatever deal any of the other men on the table make, they are obligated to give her a percentage.

Recently, she has started to seek power and prominence of a different kind. She wants to be a minister. In a sense, her ambition matches Adetiba: the director made a living from music videos and a vacuous comedy, and now she wants to be taken seriously as a filmmaker.

Unfortunately for Eniola, the barriers to crossing from the underworld to mainstream politics are higher than what obtains in Nollywood. The movie’s kingmaker, Aare Akinwande (Akin Lewis), who has needed her money and street muscle in the past, is reluctant to help her switch. The trouble, as she is told, comes down to appearances: Nobody wants to associate with someone in the light if the person has proven useful only in the dark.

As Eniola tries to find respect, one of the other men on the table, a guy nicknamed Makanaki, wants to become the King of Boys. A recent heist has given him money and with it he wants to buy power. He openly insults her; she vows to kill him. They go to both spiritual and physical lengths to fight each other. In the process, Eniola becomes entangled with these two linked tussles: on the one hand, she wants to be respectable; on the other, she is demanding respect. Her respectability problem extends to her family, where her daughter (Adesua Etomi) is appropriately reverential, but her son (Demola Adedoyin) doesn’t think highly of her.

Along with showing us how Eniola goes about solving her respect problem, King of Boys also shows how she got to the head of that table of gangsters through flashbacks. There is a lot of scheming, as you can imagine. Some of these scenes taking place in the past should be cut, but there is one pearl of a scene showing a young Eniola (Toni Tones) holding on to her dying husband (Jide Kosoko) as they are ushered into matrimony. He is well into an illness he can’t survive, but at that moment, he realizes just what trouble this young woman has become, and he also knows he’s too sick to stop her. His realization and resignation are telegraphed by the tiniest of gestures from Kosoko.

The model for this non-linear telling of a gangster’s rise is Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather II. The 1974 film showed the rise of Vito Corleone as well as his son Michael’s moves decades later. If Corleone was an Italian immigrant in the US, Eniola is a female immigrant of sorts in the land of violent men: they are both outsiders with ambition. This comparison shows the extent of Adetiba’s praiseworthy ambition but also offers a look into two of her film’s major problems.

First: Adetiba, a former music video maker, doesn’t quite have (or has not developed) the right sensibility for a character study, which to my mind is King of Boys’ true destiny. (It is why she shows sleeping crew members during the credits, a decidedly wrong move.) Because she is invested in pop and pulp, Adetiba thinks her subject is political intrigue, but that is only partly the case; her material’s true focus should be character: how one woman acquires power and how an obsession with it leads to her unraveling. Yet this doesn’t spoil the film because her central character is compelling and adequately played by Sobowale sans her usual histrionics. Even so, I left the film convinced the story would be better relayed as a linear exposition of the life and times of Eniola.

Second: Adetiba’s own obsession (and maybe identification) with her strong female character is so significant that when, towards the end, her story has to make a choice between making a feminist point and a moral one, it goes for the former, a decision that needlessly extends and mars the film’s third act. What should be a crime and punishment story or a classic rise and fall tale of this fictional overlord becomes an avenue for the dubious showcasing of female power.

Fortunately, Adetiba understands power even if she doesn’t quite understand her material. And part of her film’s lesson is that the superior group of gangsters in the modern setting is in charge of the law and its enforcement—politicians in this case. True power, King of Boys tells us, is more Putin than Tyson. Eniola’s street muscle can only go so far, and one of the film’s best scenes sees her argue, threaten, and then capitulate upon the realization that she is holding an inferior hand when it comes to state politics. This places King of Boys squarely in its time as, after the recent Tinubu-coloured primaries in Lagos and ahead of the 2019 general elections, it shows a plausible working of Nigerian politics.

Yet, the viewer who is yet to see the film is likely to want to know if she would have a good time sitting at a near 3-hour film, the greatness of Godfather II be damned. The answer to this question is yes, mostly. The story also has some genuinely interesting twists. And although the editing between scenes is choppy and the cinematography fails to conjure into existence a needed noir atmosphere, the acting is almost evenly good, with Remilekun ‘Reminisce’ Safaru and Sobowale at the great-to-exceptional end and Etomi at the passable-to-good end. First timer Reminisce plays Makanaki so well that his portrayal will inevitably become the gold standard for Nigerian rappers dreaming of the big screen.

Still, the best thing about King of Boys is off-screen. It is immensely gratifying to see a Nollywood director take on a project as ambitious as this, in duration, in scope, and at some depth. If, ultimately, Adetiba has failed to make a classic movie out of a material with that potential, she has at the minimum made a very rewarding one out of a near three-hour narrative. In Nollywood, dear reader, that is an epic achievement.