Features

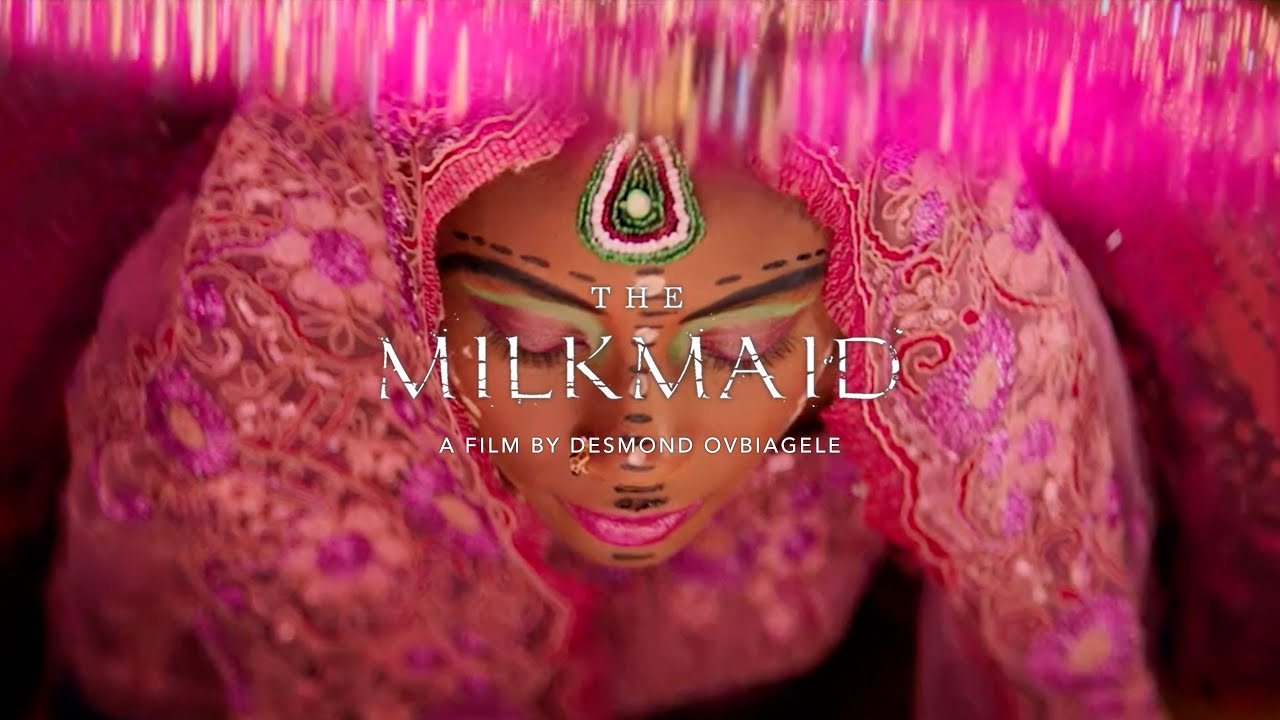

Dika Ofoma: Anthonieta Kalunta on Becoming “The Milkmaid”

Aisha, a milkmaid, escaped abduction from the hands of insurgents, only to return to them in a bid to rescue her younger sister, Zainab. They had both been initially kidnapped on a day purported to be a happy one. The insurgents had stormed Zainab’s wedding camouflaged as protective soldiers only to gun down most of the guests, including Zainab’s groom, and capture those who remained. The insurgents were jihadists and had abducted the young girls to make fellow disciples of their cause, forcing marriage on those they desired in the long run.

The Milkmaid story is inspired by the activities of Boko Haram in northeastern Nigeria. The many acclamations the film has received since its limited release include winning the best film at the 2020 AMAAs and being selected as Nigeria’s official submission for the 93rd Oscars.

Aisha is played by Anthonieta Kalunta, a Theatre Arts graduate of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Her performance in the film earned her an AMAA best promising actor nomination and recognition in many 2020 year-end lists, either as part of the top revelations of the year or on the list of actors who gave the year’s best performances.

Kalunta talks about her journey to becoming the titular Milkmaid.

Auditioning

The year was 2018, Kalunta had just graduated the year before and was now waiting for her call-up letter for NYSC, the one-year paramilitary service expected of Nigerian graduates when she got wind of an ongoing audition in Taraba state. She says she had no prior knowledge of what kind of production it was going to be, but compelled by the film’s synopsis, she decided to give it a shot.

After the auditions, still on her journey back to Zaria, she got a call from the director, Desmond Ovbiagele, asking if she could play Aisha, the lead. She said yes.

What convinced her she could play the lead?

Kalunta could never have imagined that she would be cast to play the lead. It would be her first time acting on screen, and even though she already had experience as a theatre actor and student in Zaria, she “wasn’t known anywhere else.” She was shocked and flattered by the director’s question, Nollywood is, after all, an industry where a film’s (commercial) success is heavily dependent on its clustering of stars and celebrities.

Kalunta admits that while she had been overjoyed to be cast in the film, and as lead, she had also welcomed the daunting task ahead with some trepidation, but she says,

“I have learned not to shut any door. I don’t say no to anything, I just go and study, work on myself and ensure that I can deliver.”

Working to Become Aisha

Her surname, Kalunta, betrays that she is Igbo and from southern Nigeria, precisely from Umahia in Abia state. When I asked her about the differences between herself and Aisha, I had expected her to contrast their religious, ethnic, and social class differences. She, instead, talked about their different character traits.

She finds Aisha a tad docile, but also very calculative and stubborn while she, Kalunta, is ebullient and expressive, a personality that works for her as a news anchor and TV presenter. She insists she is more like Zainab. Kalunta had, in fact, hoped to play the character due to this sense of affinity after a cursory read of the script during the auditions.

“Zainab is adventurous and willing to explore, unlike Aisha.” Then describes how alike she is with the character. “For instance, there was news (at the time) about insurgency and people dying, and this was me telling my mum that I wanted to go for an audition in Taraba,” she said. “It’s not that I had gotten the role, I wanted to try and get the role, which did not make any sense to the people that heard it.”

She continues,

“When it comes to my dreams, I’m willing to push to a great extent for the things I believe in and, you know, I want the big city. I don’t want Zaria, small and remote. I love Zaria. I love home, ‘cause Zaria is basically home to me. I want to take on more, which is really what Zainab wanted for her life: she wanted more than just the fura she and her sister were selling.”

However, the differences in character traits were not the difficulty she experienced when preparing to take on the life of Aisha. As earlier mentioned, featuring in the film, was her first time acting on screen. All her acting experience had been in theatre, while in school. The transition was a challenge for her because “on stage, you’re a lot more expressive,” she said. “But on-screen, you have to tone down a lot of that acting. While I was trying to learn that, it just happened that the first character that I was trying to play on-screen happens to be this really not so expressive young girl.”

It became easier to be Aisha as the weeks went by, she says. It helped that while on set, everyone simply addressed her as Aisha. It made it possible for her to stay in character through production.

Another hurdle to becoming Aisha was the language. It wasn’t just a few lines of dialogue in Fulfude, a language foreign to her, but also Hausa, the lingua franca of the north, despite having been born and raised in that region of the country.

“My Hausa is not as great in real life as it was in the movie,” she said. Thankfully, they had a language instructor on set, who was in charge of not only making sure her Fulfude came out right, but also that she spoke proper Hausa.

The shooting period was a stressful and difficult time for her. It was planned to be six weeks ( a really long time for Nollywood), but it was extended, and they had to be on set for three months. It exhausted her, and she had bouts of homesickness.

”That’s the longest time I’ve been away from home and from my mother,” she said, stating that she had attended university from home. To survive, she had to form bonds and create relationships on set. When they eventually wrapped, she was sad and said goodbye to her new friends with misty eyes. She’s continued to be good friends with many of them, and they turned out to be rewarding relationships, helping her navigate the industry today.

The three-month experience outside of home in Taraba helped her learn independence. “It got me used to living outside of home, and without my family,” she said, and when it was time to leave for NYSC, she was able to cope with separating from her family for a year.

The Journey Through

Kalunta remembers 2014 vividly, the year the Chibok girls were abducted – The Milkmaid is based closely on their stories. The news had depressed her and left her downcast for months. “It was really scary news that a bunch of young girls could just be whisked away and no one knows where they were, and no one knew if we would be able to get them back,” she said. Just two years before, she was in secondary school, and she imagined the absurdity of leaving for school one morning and never returning.

Her family had intended to leave the north at the time. Aside from the abduction, churches, mosques, and other public places had become target locations for the terrorist bombs. Her mother, yielding to pressures from well-meaning Igbo relatives, seemed vehement about relocating southwards.

Kalunta did not want to leave. She was already in her second year of university at ABU, Zaria, and Zaria had been home all her life. The thought of abandoning friends, school, familiar surroundings so abruptly for a new life somewhere else terrified her. In time, her mother overcame the paranoia, and they never did leave.

At that time, she could not have imagined that years later, she would be tasked to bring the girls’ story to life through a film character. The Milkmaid also highlights one of the many challenges facing young girls in the north: forced/early marriages. As a theatre arts student, she had volunteered to do community work and development communication involving women and girls in nearby villages, thus the reality of child marriage didn’t stun her so much.

“We had actually gone to work in a community where there were no girls say between the ages of 6, 7 to 15,” she said. “We had women and toddlers. Those in-between had been married off.”

In retrospect, Kalunta is convinced it was the story that made her resolve to go to Taraba for the auditions. She says, “while a lot of people may have heard about the girls’ abduction, not many know or can understand what their experiences are.” She had felt the need to be part of this film that would reveal their harsh realities to the world, and perhaps stir up conversations, and provoke actions on the ongoing scourge in the north.

“And so what a movie like this would do is to shed more light and bring it closer to people who have never experienced, or known anyone who had experienced it and feel like these are just tales. There are many things they had to go through. It is so horrible. And to think that when they come back, reintegrating back into their communities is also another problem. It is also like a curse, not once or twice, just over and over again until they lose their lives.”

It shocked her.

“I had expected that when the girls are returned to their communities, that they would be welcomed and embraced and be excited to have them back, only to find that that was not the reality. It is hard to accept them. Because they now consider them filthy, because they had mixed up, some of them had given birth to babies for these men.”

That awakened some sort of consciousness in her. When she learned about the National Film and Video Censors Board’s initial stance on the film, a refusal to let it screen due to content it considered would provoke some of the audience, it had displeased her, but it wasn’t entirely surprising. “I kind of expected it,” she said. “From the kind of things I’ve heard about the kind of films Nigerians are allowed to put out there, I felt like some things may not be accepted,” hinting at the board’s past decisions. In 2014, it delayed approval for the adaptation of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel on the Nigeria-Biafra war, Half of a Yellow Sun, to screen in cinemas because it feared it could threaten national security, and in 2019 suspended Sugar Rush after a week of screening; it was rumoured that the reason was that it did not positively portray a government unit.

Due to the film’s criticism of religious fundamentalism and other harmful cultures of the north, Kalunta had also feared attacks from individuals who may feel that their religion and culture had been lampooned. She says, “what if someone lynches us for making a film like this?”

The makers of the film compromised, chopped out 24 minutes from a formerly 2-hour film, and the NFVCB has approved it now for cinema screening. Kalunta is not pleased with this development. She’s yet to see the new cut, but it left her wondering what they could have taken out.

“I am just hoping that it wouldn’t change anything about the story, or make the audience not get the impact the movie is supposed to have on them,” she said.

She’s not talking only about cinema audiences here. She hopes people in communities affected by the insurgency get to see the film, especially communities that have stigmatised the girls who managed to flee from Boko Haram.

“I feel that the movie shouldn’t just show to the elites in the cinemas, it needs to go through some sort of outreach process where people in these actual communities can see what their actions do to these girls too.”