Scoop

Nigerian visual artists Gbenga Adeku, Dotun Popoola & Samuel Anyanwu are turning trash into impressive and valuable artworks

By Gabriella Opara for bird story agency

Gbenga Adeku

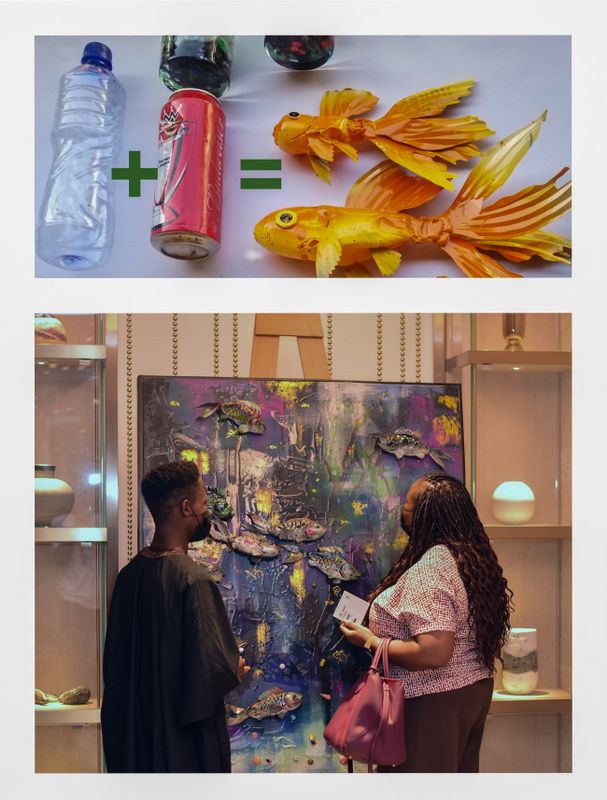

A typical workday in the life of Gbenga Adeku starts with sorting through materials in his studio, digitally sketching concepts, and collaborating with various contract workers to make his ideas a reality. Based in Osun State, Nigeria, this plastic artist is motivated to transform plastic waste into something valuable.

Adeku didn’t have this perspective on plastic art seven years ago. He had recently completed his undergraduate degree in fine and applied art at Obafemi Awolowo University but chose to concentrate on being a freelance illustrator because it paid more at the time. However, a chance encounter with Dotun Popoola, a metal sculptor, sparked his passion for creating plastic art.

Dotun Popoola

“Dotun Popoola made it easy for me to transition from being a freelance illustrator to becoming a full-time studio artist. His roadmap was also very inspirational because he is big on art that solves problems. I was keen on that, and seeing him do a lot with metal motivated me to do a lot with plastic,” said Adeku.

In 2018, Adeku started a full-time career as a professional upcycling artist. He founded his studio, Orinlanfiju, in collaboration with his father, Segun Adeku, after being awarded a grant by the International Breweries Plc’s initiative for Kickstart.

“When I saw an article online indicating that a PET bottle might survive between three and four hundred years before it starts to break down, it gave me the idea that plastic could be a resource. It turns into microplastic. So it will be present everywhere, including the air and our food. I came to the conclusion that upcycling is a better approach to taking waste and turning it into something of higher value even before it becomes waste,” he said.

Adeku has been creating upcycled art for four years.

“I used to collect PET bottles and other recyclables at events. I now purchase used plastics from local women after setting up my studio. It is quite affordable. A dozen for a penny, so I get a lot. My group and I collect, sort, and then use heat to shape them. We experiment a lot; some of them work, and some don’t. But, most often, we get interesting results, even if we have to spend months working on each part,” he said.

A recent collaboration with Nike’s flagship store in Nigeria will help transition Adeku’s signature art of ants and fishes to merchandise.

“Fish signify aquatic life, whereas ants stand for terrestrial life. Because ants rely on waste to sustain their economy, I think they are environmentalists. An ant is never broken because it works hard every day and finds things along the way. It gets around barriers. Nigerians are extremely resilient, like ants. This was the idea that rubbed off on Nike when they decided to open their flagship store in Nigeria; the idea of “just do it” syncs with my art. African boundaries are not a barrier to ants, fish, or climate change,” he explained.

Dotun Popoola, a metal sculptor, has a similar perspective on his work. He recycles metal that owners have abandoned to protect the environment.

“I like what I do since it contributes to the important elements of the Sustainable Development Goals to protect the environment. My metal sculptures are a protest against environmental decadence and the necessity to repurpose and upcycle the vast amount of trash that is endangering the earth,” said Popoola.

There is a distinction between recycling, repurposing, and reusing. As an upcycler, I give dead things a meaningful new life while preserving the earth. I feel like I’m one of the people saving this environment while making art, playing my role powerfully,” he added.

He asserts that raising young people to be change-makers and environmentalists in their own right is another method to protect the environment. Explaining his passion for mentorship, he says:

“Over the years, I have tried to encourage young people in Nigeria and around the world. I had ten outstanding sculptors exhibit in my studio in October and chose five top ones, some of whom will go for residencies in India, and another will receive a residency in the USA. The fact that I can make a difference in their lives is a fantastic privilege. I see it as empowering and contributing to society, which is one of my core values.”

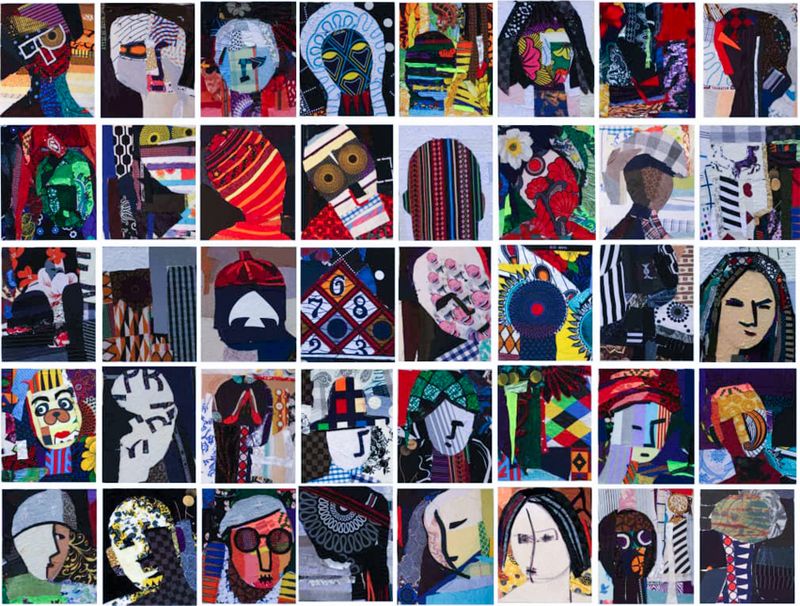

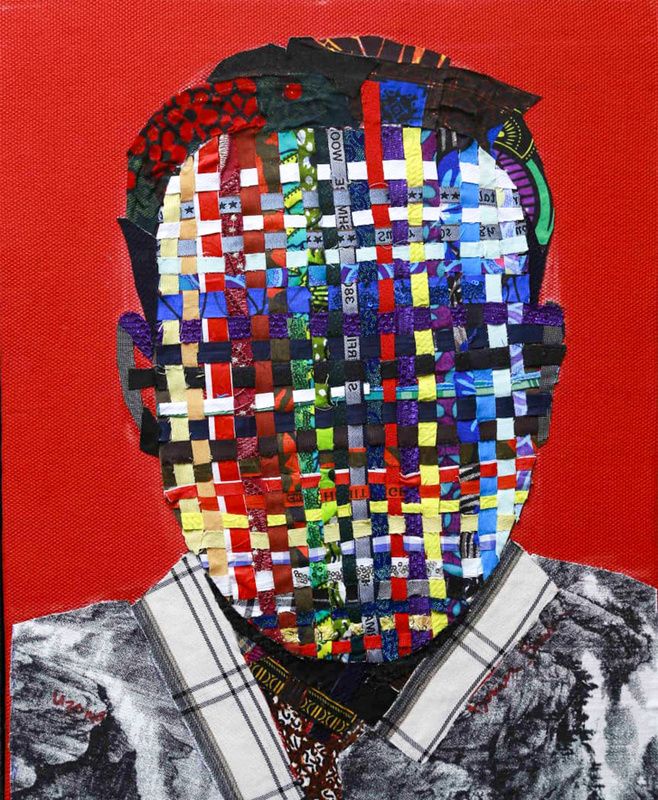

Elsewhere, Uzoma Samuel Anyanwu, who grew up in a home of tailors, had firsthand experience with the effects of fabric waste. To solve the problem, he quit his job as a full-time photographer to become a textile artist in 2012.

Uzoma Samuel Anyanwu

Anyanwu, who describes himself as an experimental artist, combines his abilities as a visual artist, a photographer, and an upcycler to produce portraits on canvas using fabrics. He views it as a lifelong endeavour rather than merely a studio practice.

“Fabrics have long been the object of my attention. I’ve been tinkering with them ever since I was a baby. My mother was a seamstress, and she taught my siblings and me the trade. Many individuals view my work but don’t grasp its fundamental concepts. I’m pleased that they love my work, but I also use it as an avenue to educate them about upcycling and climate issues,” he said.

A decade after he started, Anyanwu is still struck by the amount of fabric waste he can get his hands on. With studios in Lagos, Owerri, and Port Harcourt, he gets access to discarded fabrics from fashion houses, tailors, and markets.

“We really can’t use them all up at once. We receive sacks of fabric, but we don’t even use them for a year or two. We return to the fabrics after researching them. We never throw fabrics away because they’re always useful to us,” he explained.

Sourcing for fabrics is easier than he thought because discarded pieces are everywhere.

“We approach some people, and some approach us instead. Some offer us large quantities of their fabric trash for free; others sell them to us at a low cost. The most I’ve paid for a sack of fabric pieces is N8000 (approximately $18). We usually get bulk fabrics towards the end of the year because that’s when tailors are sewing Christmas clothes for people and everyone wants something trendy. Old fabrics get thrown out; new fabrics leave pieces behind.”

His work as a fabric artist is a community endeavour. The amount of work needed to find fabrics, learn about them, classify them, draw them, and make collage art keeps his studios busy all year long. Because of how time-consuming the work is, Anyanwu outsources some of it to contract staff, which sometimes includes his neighbours.

“Telling stories is my profession, and I spend a lot of time researching each fabric’s backstory to ensure that I accurately convey it. I have to hire individuals on an hourly, daily, or weekly basis depending on the workload for each project because it takes so much time and is so stressful. My assistants, mentees, and interns participate. I occasionally ask my neighbours and relatives for help, and we all work together,” Anyanwu said.

Despite the months and years required to source their art materials, one thing that drives these artists is the desire to see a cleaner, waste-free environment.