News

BN Prose: Fragile Nigeria, I Hail Thee by Lisa Baskett

I had narrowed my choices to three schools; each school had unique qualities that I liked. I enjoyed the city vibrancy at the University of Lagos. I fancied the idea of studying medicine at the University of Ibadan, and my walk through the Lion enclosure at the university zoo reminded me of the dominance and prominence the college bore. The faculty and staff were among the best in the nation and their research distinguished them. The idea of belonging to one of the fraternities, which handed out free t-shirts to the visiting prospective students, intrigued me. However, I fell in love with the natural landscape at Obafemi Awolowo University and I consequently studied Computer Science and Mathematics there on a full tuition scholarship. Even though it lacked the vibrancy of Lagos and the prestige of Ibadan, I flourished there.

I had narrowed my choices to three schools; each school had unique qualities that I liked. I enjoyed the city vibrancy at the University of Lagos. I fancied the idea of studying medicine at the University of Ibadan, and my walk through the Lion enclosure at the university zoo reminded me of the dominance and prominence the college bore. The faculty and staff were among the best in the nation and their research distinguished them. The idea of belonging to one of the fraternities, which handed out free t-shirts to the visiting prospective students, intrigued me. However, I fell in love with the natural landscape at Obafemi Awolowo University and I consequently studied Computer Science and Mathematics there on a full tuition scholarship. Even though it lacked the vibrancy of Lagos and the prestige of Ibadan, I flourished there.

Four years later, I walked across the stage at my graduation ceremony, to a standing ovation, as the valedictorian. I had five honor cords around my neck and I wore a medal, which I received from the Dean of my department for my academic excellence. At the end of the ceremony, I posed for pictures with my family and friends. The entire graduating class was summoned to a class picture session. The photographer asked us to smile and we did so with alacrity. We all had reasons to smile. Everyone had a job offer and some of us had scholarships to further our education in the United States and England.

I had both. I had the option to both serve my country through the Nigerian Youth Service Corps and start a career or to earn a doctoral degree in Advanced Mathematics on a scholarship at Cambridge University. I chose the former.

My first job at Shell Oil Company came laden with benefits. I had health insurance, a company house, car and driver, an annual Christmas bonus, and severance. Three years later, I met my wife Chiamaka, a burgeoning gynecologist, who graduated from the University of Ibadan. We spent our Friday nights either visiting the cinemas around Lagos or at the National Theatre in Apapa. Our favorite dramas and musicals were those that spoke of national pride and heritage. We were proud Nigerians. On Saturday mornings, we would fill the trunk of y car with coolers of food and drinks and head to Takwa Bay or Badagry beach with our friends; they were doctors, lawyers, engineers, and teachers. We enjoyed watching the waves hit the shores and star gazing at the unobstructed night skies.

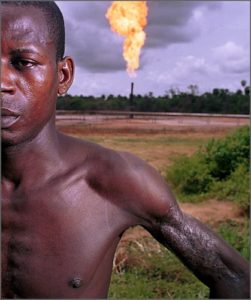

Three years later, we celebrated the arrival of a new decade with food, laughter, and fireworks on a pristine beach in Ivory Coast. If the past was any indication, the 80’s was going to be a golden era. Vast oil reserves were being discovered in the Niger Delta, infrastructure was developed, and our educational system was among the best on the continent. In addition, we had a peaceful, albeit highly fragmented along ethnic lines, country. This was right time for Chiamaka and I to join our numerous colleagues in fulfilling our reproductive responsibilities, and we did so liberally, just like our friends.

The next year, we brought Nnamdi home to his beautifully furnished nursery. Everything in his nursery had been imported from abroad. His diapers were from London and all his toys were from America. Eight days later we closed a section of our street in Victoria Island for his naming and dedication party. A year later, we did the same thing when our twins, Chuka and Chuma, were named. We needed extra help with our growing family and demanding work schedules, so we hired Ezerigbe, as a washman; Samuel, as a gardener; Yusuf, as a gateman; and Ekaette and Ngozi as househelps. Oh, I nearly left out Marcus, a Lagosian from Isale Eko, whose job was to drive the children to school and back. He also drove them wherever they demanded. I remember screaming at him in disbelief and anger, the day Nnamdi happily told me that he had taken him to Apapa amusement park.

In 1985, I returned from work with surprise tickets for my family. We packed our luggage and headed to London for a two month vacation. It was during this time that my princess, Chioma, was born. Chioma was very beautiful and everyone who saw her remarked on how she would break hearts in the future. We returned to Lagos with our bundle of joy and Chiamaka decided to become a full time housewife. I welcomed her new role with open arms especially since the demands of my job had increased. I was in America this week, London, the next week, and Angola the next two weeks. Of course, I was well compensated for my workload; there were family vacations, company parties, memberships to Ikoyi club, and other luxuries. I returned from Hong Kong in 1987, to find Uzoma, my fifth child, and yes, we celebrated his arrival in our fancy Lagos style.

The 1990’s rolled in with class at my chieftaincy party in my hometown in Ogoni. However, I realized that the glue which bonded my fragmented nation had started to erode. The materialism developed during the last two decades had finally come home to roast. National pride and identity diminished and everyone desperately desired a piece of the “Nigerian dream.” Corruption became the order of the day.

There was a police investigation into the financial scandal between my department and the Accounting department. I chose to cooperate fully with the police since I was innocent; a decision that forever changed my life. I was fired by my boss. My house, cars, drivers, and paychecks were gone in the twinkle of an eye, and I had little to fall back on.

The military coup had succeeded and the scales of justice were tilted in favor of the rich and connected. All the billions of dollars from the oil produced in the ruins of my backyard were siphoned to bank accounts in Switzerland, London, and other developed countries. I couldn’t return to my homeland in the east because of the extreme anxiety I suffered whenever I drove on the eroded and potholes-filled highways. My mind would constantly replay the tale of the family of 6 who died in a ghastly roadway collision with a trailer. At other times, it would play the video of the horrific luxury bus crash, which killed all the passengers and the tales of armed robbers only added to the torture of road trips. Unfortunately, the skies offered no relief. I knew the state of disarray the aviation industry was in. The stories of incompetent pilots and outdated infrastructure abounded. Besides, Ogoni had nothing to offer me. The rivers and streams, which I had frolicked and fished in as a boy, are now covered blackened with oil slicks and the blue skies are darkened with smoke from gas flaring. The plethora of birds that nestled in the trees of the Niger Delta have long since permanently migrated, and the ecosystem is unbalanced. The acres of farmland, which had made my grandfather and my father respected farmers in Ogoni, now lay barren, unable to produce the big yam tubers, cassava, and palm oil they once coughed up with ease. And this is true through all the Niger Delta. Food is scarce and people are hungry. Maybe I would have found solace in the company of my people if asthma and other air pollution related health illnesses had not enervated them. Unfortunately, the healthy ones that remain are too busy wrapping their muscled chests with bullets, touting AK-47s’, and recruiting the next generation as militants. They say they are fighting the oil companies and government for our rights, but I don’t think they are ameliorating the situation. The last time I checked, they perpetrated the state government election fraud; they raped our young girls and forced our boys into violence; they kidnapped oil workers and held them hostage, only to release them after huge million dollar ransoms were paid; they murdered Chinedu, my brother’s son, because he refused to be drafted.

So I searched aggressively for a job in Lagos. Government policies had stifled economic growth and unemployment had soared to unprecedented levels. My futile 3 year search culminated in entrepreneurship. I started a small IT firm, which posted a net loss in its first 5 years. I accrued debt and my large family suffered. We had little food and we shared a one bedroom apartment. On more times than I can remember, I was harassed by my landlord for failing to pay the rent. My electricity was disconnected for 2 years by NEPA, and my neighbors delighted in my plight. They mocked my family. They commented on the secondhand clothes we wore, the school my children attended, and my failure to provide adequately for my wife, whom after 5 years of job hunting had resorted to selling snacks in the market.

The year my company registered its first profit, a dismal 0.05%, was also the year when my neighbors and landlord began singing my family a new song of praise and respect. I had gotten a H1B visa, otherwise known as a work visa, to America. I relocated to California where I worked as an IT consultant with a startup computer firm. Although I was paid an enviable salary, I lived an extremely frugal life in America. I drove a very old Honda Civic and I shared an apartment with 3 Indian co-workers. I invested a year’s worth of savings in a plot of land in Lekki. My destitute days were finally over, or so I thought. There was no more embarrassing days filled with nagging debt collectors; my children were in good schools, and life was good. However, my upward mobility came to a screeching halt after just one year of prosperity. I lost my job in the dotcom burst. I was disappointed, but hopeful. I knew I could survive in America with odd jobs. I quickly got a construction job and labored from sunrise till dusk building the mansions that sprouted around California. I spent my nights glued to my computer sending out resume after resume, because the clock was ticking. I had 180 days to find a new professional job before my lost my skilled worker status.

Nnamdi’s high school graduation coincided with the day I became an illegal alien. Tears flowed from the side of my eyes as I informed my family in Nigeria of the news. I heard the sadness in Nnamdi’s voice when I told him that he could no longer study engineering in America. I obviously could not afford the tuition with my salary of $7 an hour. I was optimistic that with his perfect grades on the WAEC and NECO exams he would be admitted into a public university in Nigeria. With the exception of the twins’ high school graduation, little progress was made in the years that followed. The twins joined Nnamdi in the hunt for college admission. They were just as ambitious as their older brother, and had graduated with distinctions. Chuka wanted to study Computer Science, while Chuma wanted to become a lawyer. For two years, my brilliant boys sat at home because of the strike at the public universities. Private universities were not an option. I couldn’t afford them.

When Chiamaka came down with tuberculosis and could no longer work, the boys took out menial jobs to support the family. Nnamdi worked as a bus conductor, Chuka wrote internet scams, and Chuma taught kindergarten; however, he joined Chuka in his fraudulent ways after watching him use the $8000 he stole from a naïve woman in Ohio to fund his education at Covenant University.

On October 1st, I watched as my country celebrated its 50th independence. But I did not celebrate. There was nothing to be joyous about. I am typing this journal entry from an immigration detention center in Los Angeles because of Nigeria’s failure to provide for its citizens. My deportation was scheduled 3 months ago for later this evening. By the way, I am not sitting here by choice. I’m sitting here as a result of my desperation. I attempted to legalize my status by doing the so called “green card marriage.” It was my only option if I ever wanted to work a professional job in America. I was very hesitant about it, but I was urged on by the success of other immigrants. My Ghanaian friends had done it. Mr Jimoh, my Nigerian friend, did it as well. He makes a six figure salary as a neurosurgeon in Orange County. I just happened to be unlucky; the African American woman I had paid to marry reported to the authorities. She claimed her conscience disapproved of my action, yet she never refunded the $5000 I paid her for the deal. In the summer, men in black uniforms stormed my job at the Cheesecake factory and hauled me to this detention center in handcuffs. I have decided to tell my story using my allocated 30 minutes of weekly internet time.

By the time I land in Nigeria later tonight, 17 Billion Naira would have been spent on the independence celebration while our country lies in ruins. Our educational system is broken; our health system is nonexistent; HIV/AIDS is prevalent; innovation is low; electricity is absent; corruption is rampant; and the future of our youth is uncertain. I will arrive in Nigeria with nothing, and I have nothing there. Nnamdi died when his bus plummeted off the third mainland bridge. Chuka and Chuma were apprehended by EFCC for internet scams and fraud. Chioma relocated to UK, where she is studying accounting. Uzoma is trying to gain admission into the University of Abuja. He wants to study Medicine, but I’m too timid to tell him to dream lower. Chiamaka, the love of my life, recovered from her tuberculosis, but she has left me for a senator in Abuja. The plot of land was repossessed by the Lagos state government. I hear they want to build an airport on it. My fragile Nigeria, I hail thee.

Photo Credit: http://www.chrishondros.com