News

Ainehi Edoro: The Wondrous and Terrifying World of An Abiku

My interest in the Abiku phenomenon began when I received a short story submission from Ayodele Olofintuade, the endlessly brilliant Cassava Republic author.

My interest in the Abiku phenomenon began when I received a short story submission from Ayodele Olofintuade, the endlessly brilliant Cassava Republic author.

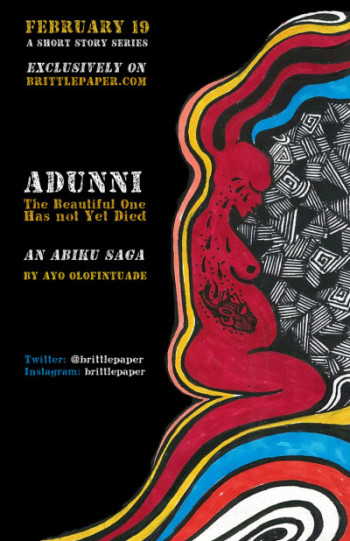

Immediately I read the story, I asked Ayodele for seven more and commissioned Laolu Senbanjo of Afromysterics to do the accompanying images. That is how the story series, “Adunni: The Beautiful One Has Not Died”, was born.

The story is set in present day Lagos. Adunni is not your regular Abiku. Powerful and calculating, she puts a lot of thought and research into choosing her host mother. Envied by all, loved by Mother Earth, Adunni thought she was invincible. But her luck runs out when she is born into the Lamorin family.

From speaking to Ayodele and doing a bit of research, I found out that so much of what the average Nigerian knows about the Abiku phenomenon is shrouded in misinformation. My research uncovered a 1973 text written by Timothy Omobolade and published in the Journal of African Arts. Keep reading if you are interested in the wondrous, terrifying, and mysterious world of the Abiku.

Abiku, as you may know, is a child who is born but who then dies willfully. Sometimes, the same child is born many different times into the same family. The idea of an Abiku—someone who is born to die—may seem strange to us. Life is so precious to us that it seems utterly unbelievable that a person would look forward to their own death, orchestrate it, and even crave the experience of dying. But Abikus are not human like us. They are spirit beings. They may look like children, but they have been in existence, sometimes, from before the Great Flood.

Sighting a suitable pregnant woman, an Abiku enters her womb, shoos away the fetus already growing in the womb, and positions itself in there. Abikus tend to hang out in unfrequented peripheries of neighborhoods. They like forests, bush paths, and roads. They also like living inside trees—enormous and sacred “trees like the iroko, baobab and silk-cotton.” They are also fond of hanging around ant-hills and dung hills. Pregnant women anxious to avoid running into an Abiku avoid places like these, especially, right before the day breaks and during really dark nights. Apparently, Abikus also come out when it’s hot and sunny.

Is there a standard life cycle for all Abikus? No. Every Abiku tells Mother Earth how long it intends to stay and does everything it can to stick to that time frame. Some Abikus pledge to die a few days after they are born or months. Others might stay till right after their wedding night. They may choose to return to the same family several times until the mother’s body dries out with age or decide to make their rounds with different mothers.

During their stay in the human world, Abikus seek each other’s company. When the whole household is fast asleep, the infant transforms itself into a grown-up and goes off to meet with other sojourners like itself. Right before dawn, it returns to its mothers side, re-transformed into the body of the infant.

Above all else, Abikus want power. The endless cycle of death and rebirth can be tough, so deep down Abikus envy humans their mortality. They can never experience the peace that only death can bring. But an Abiku is a slave to its desire for power. It is power that makes the incessant comings and goings all worth it. There is a financial dimension to these desire for power. If you’d like to know more about this aspect of an Abiku’s life, read Amos Tutuola’s novel, “My Life in the Bush of Ghosts”. Anyway, parents give everything they own to keep the child from dying, whether in the form of money spent in treating incurable illnesses or money spent visiting the Babalawo. Every penny the parent spends, enters the Abiku’s bank account, so to speak. You may not know this, but the tears shed by the mother for the death of an Abiku is more precious that diamond. The Abiku collects it and sells it very expensively in the spirit world. This also accounts for why Abikus prefer to die young. Dying young, beautiful, and deeply loved means more tears, more sorrow, more pain for the mother—all things that the Abiku needs for power, wealth, and fame in the spirit world. Indeed, Abikus are known for their beauty.

Is there a way to cure the Abiku of its obsession with dying? I will list three: A visit to the Babalawo (or perhaps a pastor) is the knee-jerk reaction of many parents. The Babalawo tries all he can to “earth” the Abiku. Earthing is the word for forcing an Abiku to adopt its human family as its true and only family. But, as my source notes, “Abiku children have no respect for the Babalawos (and presumably pastors too), considering them to be so much “mumbo jumbo.”Whenever they can, Abikus like disgracing Babalawos (and of course pastors) by showing how ineffectual their remedies are.

Another technique is naming the child. It could be a name that begs the child and tries to cajole it into staying like:

“Durojaiye (Wait and enjoy life); Pakuti (Shun death and stop dying); Rotimi (Stay and put up with me); Omolelebe (the child should be appeased); and Eloe (Appeal).”

It could also be a name that is more hopeful like:

“Igbekoyi (Bush [the popular cemetery for the Abikus] has rejected this [Abiku child]); Kokumo (It does [or will] not die again); Ajitoni (It wakes up [and is alive] today, and therefore we wish it many happy returns); Ajeigbe (Monetary expenses are never a waste [as our expenses on you shall be no waste]).”

A name of complaint:

“Kosoko (No more hoe is available [to dig any grave]); Jolokoosimi (Let the owner of the hoe take a rest); Anwoko (We are yet to find a hoe [to dig a grave]).”

Lastly, a name of contempt:

“Kilanko (Wherefore should the naming be ceremonious?); Oku (The dead, the deceased); Aja (A common dog); Omonife (It cannot be known by any better name than the mere one of a ‘child’); and Tepontan (No longer feared, respected and cherished).”

When all else fails and the Abiku has refused to stay and has the audacity to return, the dead body of the Abiku is mutilated. The fingers could be cut off, the corpse burned, etc. The idea behind this is that even though Abikus shuttle between the spirit and the human world, this, admittedly, hectic life is not supposed to take its toll on the Abiku’s body. An Abiku could be excommunicated for returning to the spirit world with a burnt body or a mark running down its back. Banished from the spirit world, it is forced to make a life for itself in the human world.

This is really just scraping the surface of all that is known about this strange and bewitching caste of spirit beings. Now imagine a story woven out of the lives of these strange beings, loaded with the drama of betrayal, a mother’s undying love, a child’s terrifying desires, a pastor’s greed, a Babalawo’s wisdom, a witch’s plea, petty gods, clueless humans. Yes. All these and more is what you’ll get in Adunni’s spellbinding story. Her story begins at Brittle Paper on February 16th. Brittlepaper.com. Don’t miss it.

Images by Laolu Senbanjo: Read the BN Feature of Senbanjo’s work {HERE}.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Ainehi Edoro is a doctoral student of literature at Duke University where she studies African novels. She is also the founder and editor of the African literary blog called Brittle Paper.