Features

Keside Anosike: An Insight into Wana Udobang’s Spoken Word Album – In Memory of Forgetting

After any trauma, we never really know what to do. The human body and soul, still in shock, negotiates the act of forgetting what has happened and the act of recovering from it simultaneously. It is easy to feel like one is in limbo, unsure whether to recover, or to forget; if recovery itself meant forgetting, and if an inability to forget is spelt an unhealing.

Wana Udobang’s sophomore poetry album is the limbo we very often find ourselves in. But with “In Memory of Forgetting”, the narratives are tailored from the poet’s personal experiences, and the miracle is that we get to feel each retelling, as though we had been one with her on the journey. Memory is a ghost; memory is a veil. Memory has a way of refusing to be forgotten.

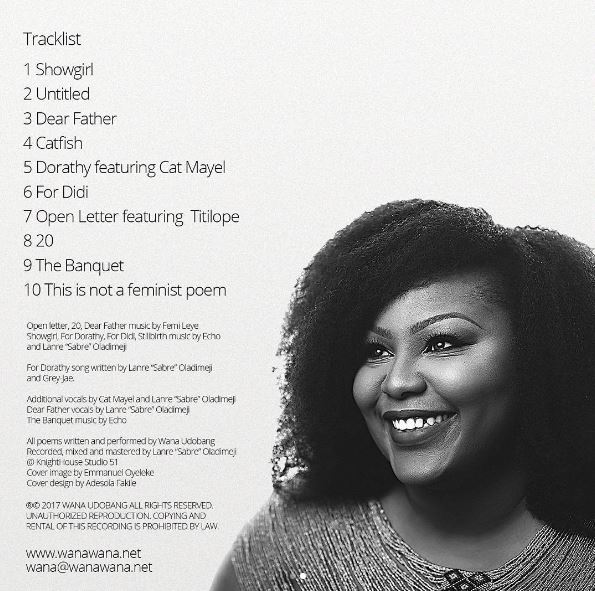

“In Memory of Forgetting” opens up with “Showgirl”, an unassuming track with smooth elements of jazz. To this poem there is a sense of youthful seduction, an almost sultry composition that welcomes just as it holds back. “Showgirl” doesn’t prepare the listener for what follows: “Untitled”- a cold eerily narration of abuse; and Dorathy (featuring Cat Mayel)- an ode to the poet’s mother that is at once a celebration of maternal sacrifices and an admonition of traditional expectations of women.

In all tracks, Wana is unchained with unflinching honesty: of self acceptance and beauty, “The Banquet” rings with a plethora (and the importance) of reaffirmations; “Dear Father” addresses her estrangement with her father, how their relationship is both complicated and liberated by the presence of her memory of him.

“For Didi” tells of a dear friend’s journey to motherhood, and eventually, parenting a disabled child; “20” is naked with longings and warm desires; and bitter questions are asked from start-to-finish in “This is Not A Feminist Poem”.

Each track on “In Memory of Forgetting” falls into the other seamlessly, echoing lines about identity, hurt and the grace in healing. The production is flawless- strong, but not at all intrusive so that the balance between word and sound is poignant. I believe the sound that carries each poem gives it a certain charge, and one is unsure if, when stripped of their sweeping orchestra symbols, the poems can sit on their own emotional weight. But I am willing to gamble on that.

Wana’s natural voice is very compelling- its soft, raspy tone succinctly measured with her breathing makes one uncertain what mood she is in. In conversation with my sister about In Memory of Forgetting, she had confessed: it is the voice; it just makes me want to cry.

On the seventh track on the album “Open Letter”, Wana and poet Titilope Sonuga strike the cords for sisterhood with words and worlds that are so inclusive; it is difficult to feel isolated- locked out. Beyond the merely collaborative or technically proficient – when their expressions become as easy and graceful as friendship or love – these poets add to the overall search for a sense of comfort in memory that this album is ambitiously set on. It is this search for comfort, this search for freedom and acceptance, this search for a set of warm bodies that would understand, that makes “Open Letter” one of its standout tracks.

There are, more than often, two ways to count a story. First you tell it the way it happened. Then you tell it the way your memory allows you to. At its listening party two weeks ago, Wana confessed her vision for this work. It was a deliberate conversation with memory, both in how the events (that she’s written about) occurred and how she had chosen to remember them. Addressing extremely sensitive subject matters, Wana’s album is incredibly brave with the complex sentences as with the trivial ones. Every word, every verse, is laden with purpose, and pass through each other like fitful lights through smoke, like a touch in the dark, really, a touch that doesn’t so much of frighten but comfort, a touch that signifies a presence, an abolishing of aloneness.

“In Memory of Forgetting” is not (just) altogether a collection of female marginalization, outrages, victories and entitlements. It searches beyond the eccentricities of a set gender. It, at the end, in the very last poem “Stillbirth”, addresses a common feeling that being alive necessitated: pain. “When the pain gets too heavy, open your mouth and spit it out…you must never chew, you must never swallow. There is no consolation for long suffering.”

Poetry that dares to confront real life- soul-rich-poetry, poetry embedded in pain is so easily ascribed to female narratives. But if you allow it, disregarding gender, “In Memory of Forgetting” will give you a glimpse of what we might still be as humans; a glimpse of our best selves, and of a world in which we give everything we have to others, but lose nothing of ourselves.

Memory is a ghost; memory is a veil. Memory has a way of refusing to be forgotten. Most of an artist’s work is dependent on memory. Whatever an artist puts out is the thing that has survived, it’s a testament to suffering and recovery; it is their own modest acceptance of human frailties, and, to a larger scale, how ordinary and at once similar we all are beyond the concept of time and place.

Wana accomplishes one of the great triumphs of art: reminds of our collective humanity, and this, this album, is salient proof that sometimes we have to go there to get here. That we must not cradle the ghost of things unmourned and unremembered.

***

Get your copy HERE