Features

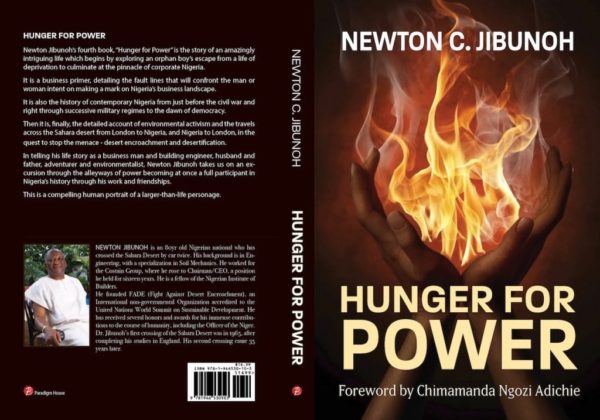

BN Book Excerpt: Hunger For Power by Dr. Newton Jibunoh

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

Nna anyi, I think the child is coming o

“Nna anyi, I think the child is coming o,” my mother whispered to my father.

“Hmm,” my father grunted. “Not now. Let’s get home first,” he added, as if, somehow, my mother had transcendent control over the timing of uterine contractions.

Seated up there at the special, reserved pew – right across from venerable clergy, no less – Samuel Jibunoh had no intention of losing face in this church his father had all but founded.

No, certainly not for something as trifling as a woman going into labour because there were far weightier matters at hand – like finishing a magnificent service!

“But my water has broken,” my poor mother complained. “We have to go now.”

“Look,” whispered my father, “I will get you someone to take you home and fetch the midwife. You’ll be fine with her. I’ll rush there immediately after. But I must finish attending this service. You know it is a New Year service.”

I had chosen the New Year service at St. John’s Anglican Church, Ogbe-ani Village in Akwukwu-Igbo Kingdom to announce my entrance into this world. The New Year church service was perhaps the one that had most sentimental traction with the church-going folks of days gone by.

My father, Samuel Jibunoh, a self-educated man who studied a bit of English and Science by correspondence, and his own father before him were pillars of St. John’s, and this situation, if not handled delicately, could prove no small inconvenience.

My ancestors had been instrumental in bringing the Anglican mission to the community by donating a tract of land for the church building that is still contiguous to the Jibunoh household today.

Mostly on account of their affinity to the church, the Jibunoh patriarchs were therefore held to a higher standard of conduct (at least when they were on the church premises!) than most. Therefore, when my heavily pregnant mother began to squirm in her seat as the Eucharist was coming to its glorious crescendo and the spiritual body of Christ Himself seemed to be descending to take up the substance of the wafers of bread on the altar, my father shot her a warning look.

Teeth clenched, grimacing in agony at labour’s onset, and assisted by a few female ushers, my mother waddled out of the sanctuary without causing the honourable Jibunoh and other worthies there present in that hallowed chamber of worship, too much discomposure at this all-important first service in the ecumenical calendar!

With the nearest government hospital a hundred miles away, my mother was now at the mercy of the local midwife, who incidentally was my father’s cousin. Popularly known as Ma Agnes, this wizened midwife who delivered me, never saw the walls of any school but midwifed almost 60% of all births in my home town and environs. She was famous and well feared in Akwukwu-Igbo and environs as a strong medicine woman. She was the go-to guy in these parts for all matters pertaining to female reproduction: our resident OB/GYN specialist.

Now, in those days, the practice of midwifery necessarily came with some connotations and not so muted echoes of fetishism. Not being regulated or totally exposed yet to modern best practices, midwifery in those days was steeped in local customs that were also shared by native doctors especially because midwifery skills were usually handed down in a family, from generation to generation – just like native doctors. It did not also help that herbs, roots, spices, tree bark etc. were the chief tools at their disposal – which also happened to be the stock in trade of native doctors. The midwife was pretty much the native doctor (‘dibia’) for women/childbirth affairs.

When it was apparent the baby was not seated well in the birth canal, my mother had to be operated on in what passed for a caesarean section. The methods in use then were, to put mildly, alarmingly basic. Locally-distilled gin was the anaesthetic of choice – and it was sometimes poured directly on the wound! The scalpel was a vicious-looking, well-honed knife. Sterilization techniques were crude. A piece of cloth was shoved in between the woman’s teeth for her to bite on to help her manage the pain.

Since there were no bed stirrups, two hefty women simply sat on the patient, one on each leg, preventing all movement. These were the circumstances in which I came into this world on New Year’s Day, 1938!

***

Newton C.Jibunoh is an 80 yr old Nigerian who has crossed the Sahara Desert four times by car. His background is in Engineering, with a specialization in Soil Mechanics. He worked for the Costain Group, where he rose to Chairman/CEO, a position he held for sixteen years. He is a fellow of the Nigerian Institute of Builders.

He founded FADE (Fight Against Desert Encroachment), an International non-governmental organization accredited to the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development. He has received several honors and awards for his immerse contributions to the course of humanity, including the Officer of the Niger.

Where to Purchase:

Online:FADE Africa website | Available on Amazon

Offline: DIDI Museum – 175 Akin Adesola Street, Victoria Island.