Scoop

An art show in Senegal aims to link Africa’s lost history with the present

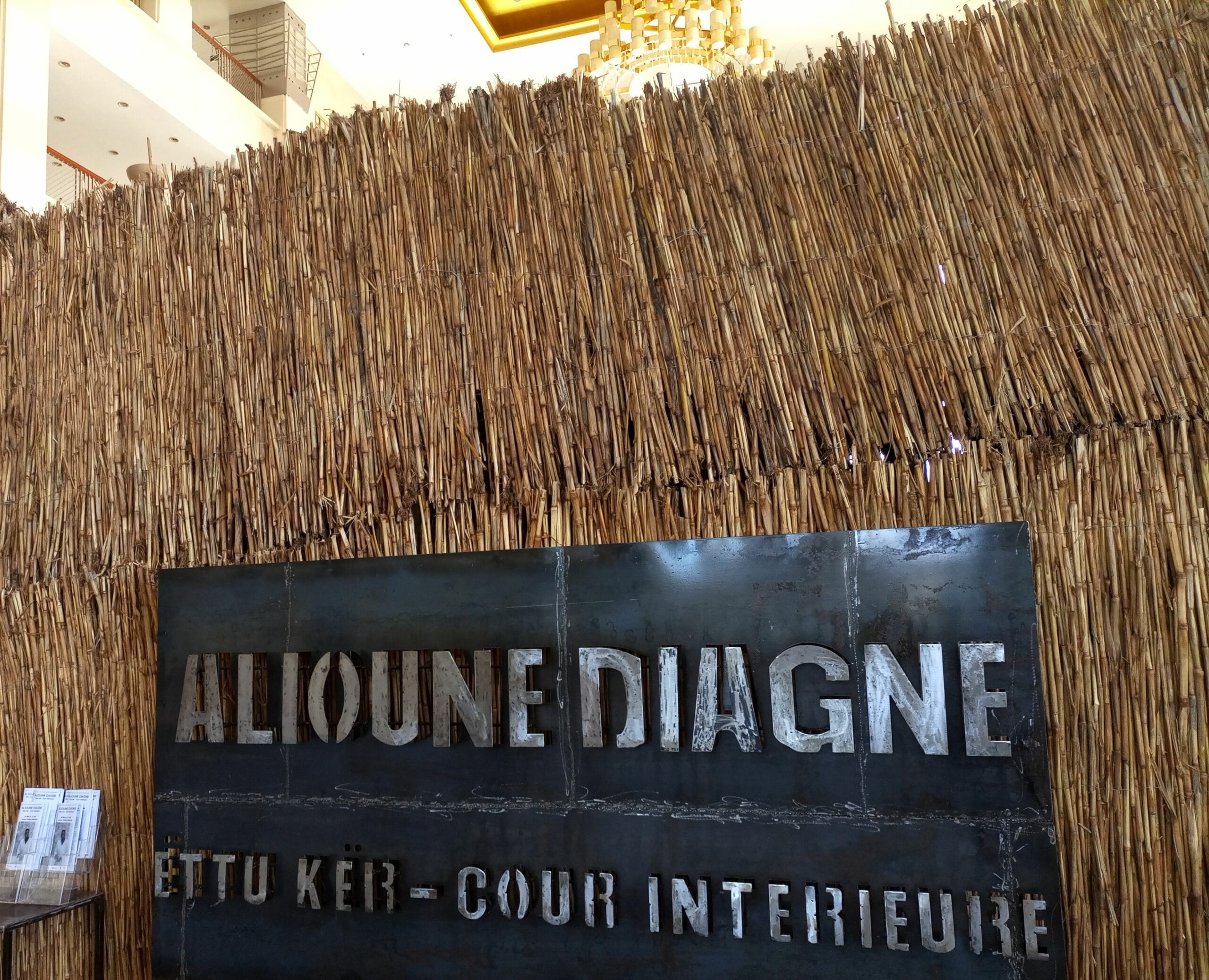

In a life-sized compound located in the heart of the marbled hall of the Doudou Ndiaye Coumba Rose National Grand Theatre, Alioune Diagne offers a retrospective of Senegal’s history. Through his exhibition entitled ‘Ëttu Ker—Inner Courtyard,” the artist reworks and revisits “postcards” dating from the 19th century.

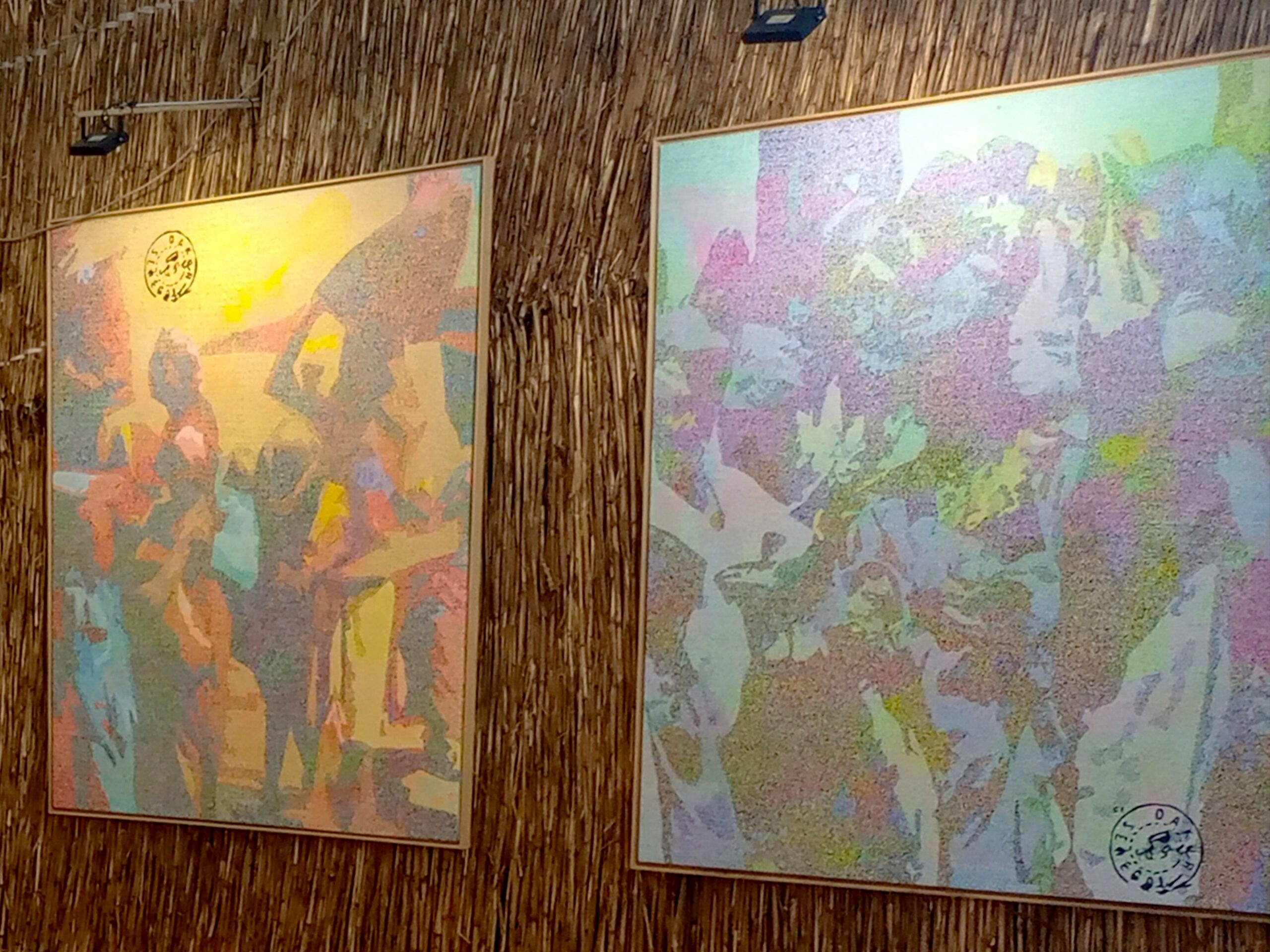

The postcards look like paintings that are hung on the straw walls of a family compound that is the same size as a person.

Alioune Diagne’s works are composed of signs—square or circular shapes—that are a vector of meaning and emotion for him. When you get close to one of his paintings, you can see that these signs are actually recognisable human figures as a whole.

Since 2018, Alioune Diagne has initiated a collection of works entitled “Senegal Memory,” which represent daily scenes from the past, translated into shimmering colours.

The series is central to the artist’s work, and over the past year, he has entirely devoted himself to the production of new paintings celebrating this theme. With a strong colour palette, the artist gives old images of new life and makes people think about how society is changing.

Alioune Diagne sees the family space—the courtyard, or “Ëttu Kër” of yesteryear—as a privileged space for socialisation, transmission, and education. He draws a parallel with the isolation we are witnessing today, despite the advent of connected screens.

He notes that the courtyard was a privileged space for bringing people together and transmitting a standard set of values in the past. Even though people live together, there is a tendency toward self-isolation that is accentuated by technology, especially smartphones and social networks. These consume a large part of human activity and offer a new form of socialisation but also isolation with a digital flavour.

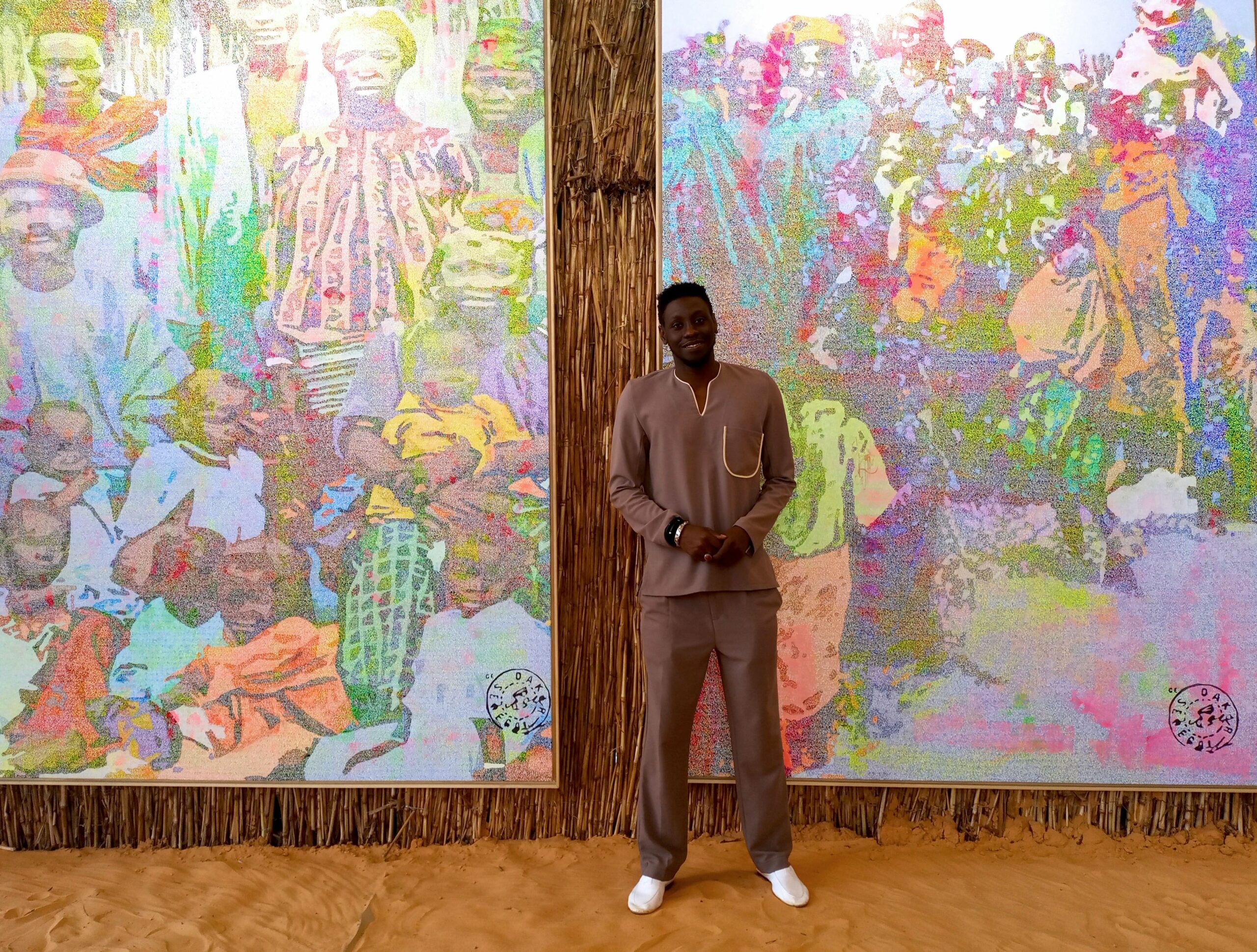

“The works presented in the exhibition Ëttu Kër – Inner Courtyard” are conceived as a dialogue between past and present times. Everyone is free to understand the images according to their own experience,” Diagne said, explaining his work.

Surrounded by a straw fence, the inner courtyard is “where family members meet, share, discuss problems, welcome their relatives,” Alioune Diagne continues. Less present in today’s architecture, or more and more seen as a place of passage, the interior courtyard testifies to a way of sharing and connecting with others.

“Life scenes and portraits are shown around two large metal sculptures that, from the artist’s point of view, show patriarchs looking down on their descendants from a distance.”

Diagne wants visitors to reconnect with these customs and the past and value the traditions. In addition to the paintings, this reconstruction shows granaries, calabashes, the pestle and mortar, the focal points of the kitchen, and a clothesline on which traditional, handmade clothes are spread.

Living between Senegal and France, Alioune Diagne uses the 19th century as a reference point for future events.

“The past is very important because the past makes the present and the future. For me, it was ideal to represent this to Africans, especially to the younger generation, so that they know that the past is significant,” he explained. “It is history, and it was important for me to share these unpublished images of Senegal’s memory. All the images are real images of Senegal from the 1800s.“

Alioune Diagne does not lack a touch of nostalgia. “It was in the courtyard that education took place. In the evening, our grandfathers gathered us and passed on stories, teaching us life lessons through tales and legends. This is disappearing, and the idea is to revisit these values, “he explains.

Born in Senegal’s Fatik region in 1985, Diagne graduated from the National School of Arts in Dakar. He moved to France, where he continued his training, consolidating his visual universe around key themes of his childhood, colonial history, and memory, with a preference for portraits and scenes of life.

He also expanded his palette to include sculpture, video, photography, and silk screening.

In 2013, he made a style of art that he calls “figure-abstro.” It is a mix of figurative and abstract art.

Photo/Story Credit: Mohamed Njim for bird story agency