Features

Aluka Igbokwe: For My Father, Whom I Love

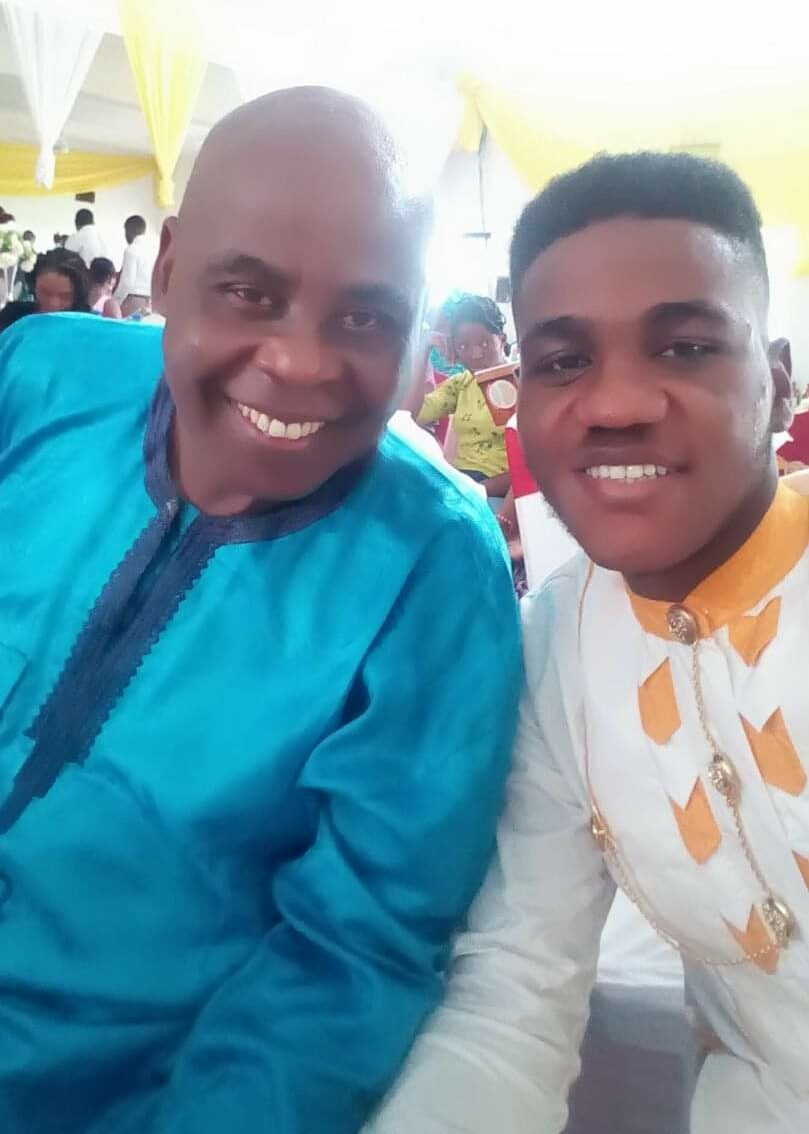

Okemmiri, every day, I’m grateful to God that I have you, still strong and alive.

When I was a child, the street children were jealous of me. My father was a strong man with biceps and triceps made invisible by layers of unwanted fat. He had caramel skin, a balding head and a chest sparsed with salt-and-pepper hair. I always sat astride his stomach, picking the hairs on his chest, and watching his face scrunch up in a wince. He’d hit me softly, saying, “nna, jiri nu ya nwayo, take it easy.” He never complained about my increasing weight nor did he complain of his chest throbbing with pain. But he did one day. And my love for him receded.

My father always carried me about. I think being the last child came with such privilege. The street children were always jealous of how high he threw me into the air. So he’d come back from work and spend the larger part of his evening taking street children off their feet and throwing them up mid-air as they shrieked – a mixture of fear, worry, joy, excitement and everything good and pleasurable. His dexterity always stunned me.

Consequently, my father had less time for me after work and more time for the street children. The street children dropped the baton of jealousy and I quickly picked it up. I felt small and inconsequential. I did not like the way my father was slipping off my hands like a jellyfish. I did not like the way he never had time to lay down and let me pick greying hair off his chest. I did not like the way he denied me his winced face which seemed glorious.

He started giving excuses for not throwing me up into the air. For not letting me sit astride his stomach. “You’re growing up,” “You’re becoming too heavy,” “I need to rest after work.” Whenever he said these, I walked away sadly. I crept under the dining table and cried. My tears tasted of anger and hate and loneliness. The street children I always played the game of Hopscotch and War Start and Okoso with suddenly became uninteresting. I noticed that I was blinded by a maddening possessiveness. And this made me lack empathy. In my desire to have my father all to myself, I didn’t realise that he was altruistic and a free spirit. My father noticed my reclusiveness. He engaged me in something better: books, stories, old newspapers, and the radio. He regaled me with stories of the civil war. Of how he stole canned salted rice from the Nigerian Army. How he ate lizards for dinner, and how he trampled on decaying bodies. He made me read old newspapers. He made me read Achebe and Hardy and James Allen. He also bought me a little Kchibo radio which I religiously listened to. I listened to BCA and Pacesetter and VOA. Telling him the news I heard on the radio during the day became my favourite pastime. He taught me how to tell the time and how to iron.

Slowly, my father turned his attention back to me. I forgave him and my love for him was rekindled. He smiled and paid rapt attention as I told him about characters I had read about. How Okonkwo’s bravery encouraged me. How offensive I found his hate for his father’s effeminacy. How angry I got when Michael Henchard sold his wife for five pounds in his inebriated state. How awestruck I was at Elizabeth-Jane’s grace.

Today, my father is a sexagenarian, and I am a man too grown to be thrown into the air. And each time I visit home, I watch him closely. How beautifully ensconced he still is in his home. How loosely he now ties his wrapper. How slowly he stirs his creamy tea. How grateful he is for little things. For life. For love. For family.

It is Father’s Day today and I find my dear father worthy to be celebrated. Okemmiri, every day, I’m grateful to God that I have you, still strong and alive. Thank you for the uncountable times you carried and threw me up. Thank you very much for being supportive amidst my shortcomings. Thank you for tolerating my obstinacy. Thank you for being my goalkeeper. Thank you for loving us unconditionally. Thank you for mother. Thank you for books. Thank you for you. I pray that you have more graceful years filled with screaming grandchildren, love, light, happiness and money. Ife gi n’amasim nke ukwu nnam.