Scoop

Benin’s 30m-tall “Amazon” statue honours the women warriors of Dahomey

By Patrick Nelle, bird story agency

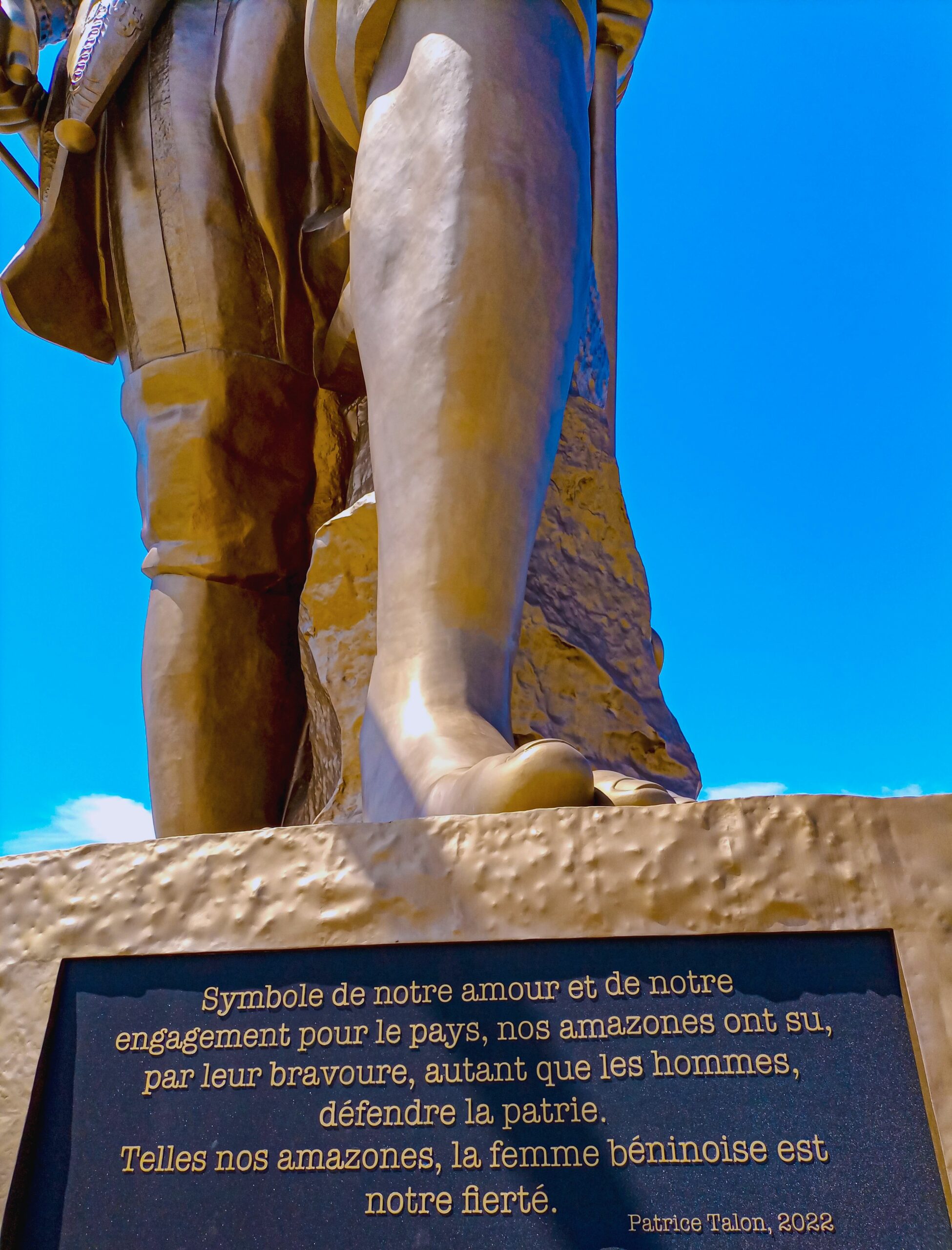

A short distance from the Marina Palace in Cotonou City stands a 30-metre-high monument called the Benin Amazone. It was unveiled this month and shows how proud this small West African country is of its history, which is slowly emerging from the ruins of colonial injustice and rewriting of history.

The small country in west Africa was once the centre of a powerful regional kingdom called the Kingdom of Dohamey. The country is becoming more and more eager to honour its historical heroes and heritage.

The statue, by a Chinese sculptor, Li Xiangqun, represents an Agoodie or Minon, a term that refers to members of a regional military corps entirely composed of women. Both admired and feared for their bravery, the Agoodie participated in most of the military campaigns the Dahome (or, ‘Danxome’) Kingdom waged against its enemies for nearly 200 years.

From modest beginnings as King Wegbaja‘s elephant hunters in the late 1600s, the women’s corp grew under Wegbaja’s son Agaja and were key to King Gezo‘s territorial expansion in the 1850s, when the kingdom expanded across most of what is today Nigeria. The group grew to about 6,000 people and was known for being fierce and cruel.

They were called the “Amazones du Dehomey” by the French colonial forces.

“This Amazon Monument aims to establish a strong identity symbol for Benin and consists of erecting an emblematic work in tribute to the Amazons of Dahomey,” the government stated in a press release at the start of the project in 2019.

In the late nineteenth century, Dahomey entered into conflict with the French, who were expanding their colonial empire across West Africa. The Agoodie were key to the kingdom’s struggle to repel French army assaults, but they couldn’t reverse the course of history in the face of French muskets.

On September 19, 1892, the Agoodie fought their last battle at Dogba, a settlement in today’s southern Benin. Dahomey’s defeat by the French military led to the kingdom’s demise and the disbanding of the “Agoodie.” Dahomey was turned into a French colony in 1894.

Independence was recovered from France on August 1, 1960, under the name of the Republic of Dahomey. On November 30, 1975, the name was changed by the then-ruling socialist regime to the People’s Republic of Benin, referencing the powerful Kingdom of Benin that existed from the 13th to the 19th century in the territory of present-day Nigeria.

The monument has drawn widespread attention, particularly on social media.

“How did I feel at the inauguration of this statue? It must be said that there was already great enthusiasm and a particular euphoria as soon as the first images of the statue were revealed. As Beninese, we feel proud that the story of these brave Amazons is placed at the heart of the country’s development,” says Zevouno Marco, a 29-year-old data analyst living in Cotonou, in a social media exchange with the bird story agency.

According to Zevouno, there is no doubt that the statue resonates widely with the Beninese.

“Any particular effect on me and the people around me? Of course it did. Just look at how we talked about it on social networks and all over the country. On the evening of Independence Day, many people were at the foot of the statue to take pictures and contemplate,” he said.

“I would even say that it’s our “Statue of Liberty,” he further stated.

“The Amazons represent a large part of the glorious history of Dahomey, and to see a statue in their honour has only made the people happy,” he concluded.

Mohamed, a student living in Cotonou, shared the same positive view of the monument. “Some people believe that such a project is a waste of resources,” he said, but went on to say he was convinced that erecting the monument in Cotonou was positive for the country and for women.

“The statue reflects success and pride. It’s also a symbol of the Beninese woman,” he said.

The statue’s inauguration is widely seen as an important step in a drive to rehabilitate and decolonise the country’s history. Another figure unveiled on the same day depicts Bio Guera, who led several uprisings in northern Dahomey before being arrested and beheaded by the French colonial rulers in December 1916.

The West African nation is also seeking the return of stolen artwork. Earlier this year, Benin retrieved 26 palace artworks that were looted when the French army toppled the king of Dahomey, Behanzin. The government recently launched a museum to accommodate the returning art pieces.

Benin hopes that the art pieces will get its own people and foreign tourists interested in the country’s history again.

“The erection of monuments is a tourist asset and gives visibility to Benin,” commented another Beninese, Nice Houngbegnon.

However, according to her, what is lacking is a more significant impact on local communities in the areas where these historical figures originally came from.

“It would be preferable for a direct impact on the community to erect monuments in their region of origin,” she suggested.

The ‘Agoodie’ originally hailed from the modern town of Abomé, which was once the capital of the Dahome (Danxome) Kingdom and is located 145km north of Cotonou, while Bio Guéra was a warrior prince from the country’s north.

Photo Credit: Abdou Rachad Moussa