Features

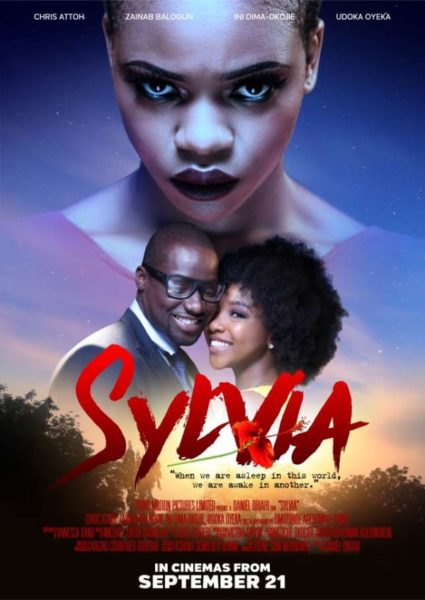

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: A Woman Scorned Does Harm in Daniel Oriahi’s Sylvia

The average Nigerian has probably heard about the concept of a spirit-spouse. Like most lovers, they are jealous and want to be the only one in your life. Unlike most lovers, you can’t really kiss them. But, as the story goes, that hardly stops them from blocking the beloved’s chances at an actual marriage.

The average Nigerian has probably heard about the concept of a spirit-spouse. Like most lovers, they are jealous and want to be the only one in your life. Unlike most lovers, you can’t really kiss them. But, as the story goes, that hardly stops them from blocking the beloved’s chances at an actual marriage.

When I was a child, the idea must have seemed vaguely disorienting: sure, I got the idea of weddings on land; but what was this mostly-marine marriage adults kept talking about? Now that I’m a weary adult, I am curious: what if it’s just a spirit girlfriend? Can’t a man enjoy the perks of marriage on earth while receiving the attentions of a side-chick in the spirit world?

For Richard Okezie (Chris Attoh) in Daniel Oriahi’s new film, Sylvia, the answer is no. He has had a dream companion named Sylvia since he was a child, but on the cusp of a relationship with a real girl, he decides to end the affair. Presumably, he doesn’t want the complication of having a spirit raise a hand when the pastor asks for objections to his pronouncement of man and wife.

Sylvia’s unhappiness at his break-up speech—which includes the callous statement, “you are not even real”—is one of the film’s early lessons: nobody knows how or why a woman falls in love with a man, but whether spirit or real, a woman scorned acts exactly like a woman scorned.

We’ll have to add Sylvia to the curious collection of women in Oriahi’s films. There are victims (Misfit and Date Night), there is a prostitute (Taxi Driver), and now there’s a witch. You might arrive at the midpoint of these films feeling obliged to yell misogyny at the screen, but by the end you could be entertaining notions of female empowerment. Let’s just call his women complex.

When the film’s trailer was released many weeks ago, I found the notion of a young Nollywood director taking on old Nigerian spiritualism immensely appealing. But I did wonder a bit about the casting.

Zainab Balogun as the title character seemed too middle-of-road an actress to work extreme devilry into her act. And Attoh has never really succeeded in convincing anyone he is Nigerian (or even Ghanaian). He gives the impression of having seen too many African-American actors growing up without learning to shed their gestures as a grown man. Squint a bit and Attoh could be Kevin Hart with growth hormone and less laughs. In other words, going by their past work, Balogun can’t quite be bewitching – either in the seductive or spiritual sense. Attoh seems unable to reproduce the body language of the average Nigerian.

When the film opens, we see an unconvincingly aged Attoh about to tell a story. It is this story that occupies a chunk of the screen-time. Of course, the major trouble with starting a film this way is the loss of suspense: whatever else happens, the audience knows Richard makes it out alive. Some directors have subverted this first-person narrative by having a dead man tell the story, as was the case in Billy Wilder’s 1950 film Sunset Boulevard. In doing so, Wilder added some darkness to the suspense: you wonder not just about the story but also ask whodunit?

Oriahi’s Sylvia could do with some darkness but that is pretty much defeated by how well-lit the scenes are. At the start of Richard’s story, Idhebor Kagho’s sunny cinematography is fitting—is there ever anything as warm and beautiful as young love? But when Sylvia is informed of the existence of the real girl Gbemi (portrayed for some reason as a giggly airhead by Ini Dima-Okojie), the mood turns but the picture doesn’t. There might be danger — you don’t cross a Nollywood spirit without consequences—but the film goes around looking like an airport.

This misjudgement colours even the very important scene of the break-up. Richard tells Sylvia it’s over, leaving her on the floor begging and crying. Abruptly, the wailing ceases, she lifts her head, and sneers at the camera. Cue Michael Truth Ogunlade’s ominous sound. You would be hard pressed to find a kitschier scene in a supposedly serious film this year.

Sometime later, Sylvia—in a remarkable turn of writing and directing—finds her way to Richard’s real life. As she tortures him, she says these words: “Revenge is like an art form, and I am like Picasso on steroids.” Now, besides the needless double simile, that is not a bad sentence spoken or written, but if we are to believe Sylvia is a goddess of prehistoric dimensions, why has she chosen such a human metaphor?

As with his previous films, Date Night and Taxi Driver, Oriahi again pays homage to some of his western ancestors. There was Martin Scorsese and Hitchcock in the past. Here there are traces of Stanley Kubrick and Roman Polanski. But that Oriahi has not become so Hollywood as to wholly give the impression that what happens to Richard in the film is clinically explicable is a judgment that deserves some applause.

It was heartening to have the origin of the spirit-spouse be broached but never really explained. The film shows it is the product of a Nigerian mind in how the existence of the spiritual realm is taken as a given, and its characters are modern figures wrestling ancient myths, citified kids fighting what we think of us as village people. But as almost every tradition in Nigeria tells us man vs myth or man vs god is not a fair fight. As Achebe puts it, “A man does not challenge his chi to a wrestling match”.

In part, this is what older Nollywood filmmakers were pursuing in bringing the Christian church into their stories, the thought being that you need a spiritual entity to do combat with a spiritual being. And it was certainly true that to win this immortal combat, Nigerians of a certain age went to churches that advertised a degree of violence, the most common of evidence of which was a vocabulary of heavy verbs: bind, cast, destroy. With the rise of prosperity Christianity, such battles are no longer the exclusive province of pastors, who are better equipped to offer their congregation business development plans anyway. That the most visible of church appearances in New Nollywood films come in romantic comedies like The Wedding Party is telling. The church might not be needed for showy spirituality but it is necessary still for flashy matrimony. And by excising the church from Sylvia, Oriahi shows an understanding of this paradigm.

Oriahi has toughened up in one regard: he has a better handle on narrative realism. Back when he made Taxi Driver, I wrote that that film had the chance to be truly tragic but the director shirked his responsibility to the story to save his protagonist from death and his audience from shock. I am happy to report that there is a remarkably bloody scene in Sylvia that must have been the source of debate during filming. The scene could be better-staged and it really should be Sylvia’s last scene. Still, I applaud the bravery of the filmmakers for keeping the scene and for their overall imagination. You would too.