Features

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: The Fatal Mistake of Ramsey Nouah’s New Take on “Rattlesnake: The Ahanna Story”

This year, the new Rattlesnake falls into the same type of trap as last year’s Living in Bondage did: the filmmakers think of cinematic storytelling, in today’s Nollywood, as excursions of glamour. But where Living in Bondage had a decently cohesive script to work with, the screenplay for Rattlesnake (subtitled, The Ahanna Story, and directed by Ramsey Nouah) has too many gaps.

It wants to be a political film but doesn’t seem to stand for anything important. It wants to be a character study but doesn’t invest anything of weighty psychological consequence in the characters’ backstories. It wants to be a thriller but lacks the genre’s inventiveness. It wants to be a romance but has too many other things going on. It may want to say something important but lacks the eloquent clarity of the Amaka Igwe original.

Much of the older film was an exercise in Nollywood grit (you can find portions of it on YouTube). In the current one, much of that grit has been replaced with a kind of glamour that has its potential for vulgarity muted by the talented cinematographer, Mohammed Atta. Several interior scenes are shot theatrically dark, a bit similar to Yinka Edward‘s work in Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart, but the problem here is not really one of skill, it is a philosophical problem: the filmmakers just don’t understand Nigerian poverty. Even when the film’s characters are supposedly having a hard time financially, they maintain their well-coifed prettiness and sophistication. They are like your rich neighbours playing at suffering because the maid hasn’t arrived.

As a boy, the lead character, Ahanna, sees a robber being burned alive on the streets and makes a vow to end up differently. But it seems like a stretch for that to be the conclusion a kid (or even an adult) draws from that event. Later, his father dies and he is left in the village while his mom and uncle go on to Lagos. He moves to the city as an adult but is greeted with theft on his very first day. It’s just his luck that that will not be the harshest thing that happens to him in Lagos. A bigger tragedy awaits.

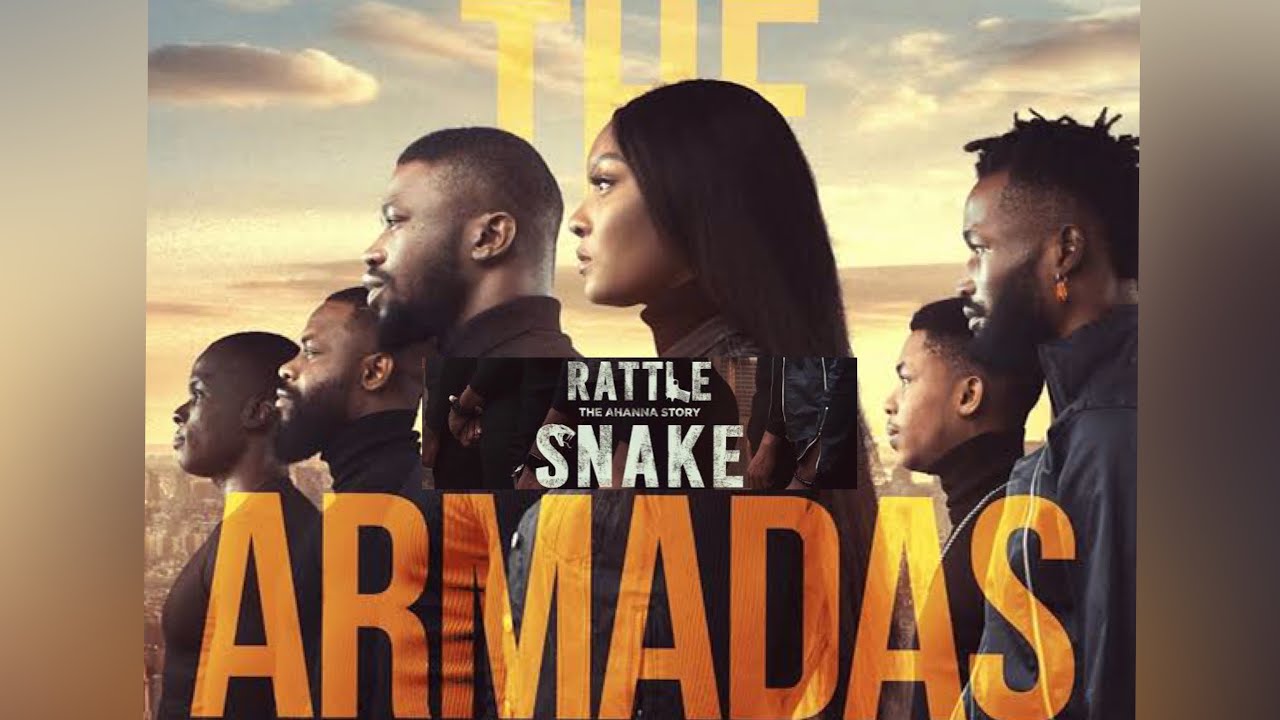

Despite the tragedy, Ahanna moves and moves, teaming up with his childhood friend, Nze (Bucci Franklin), Nze’s sister, Amara, (Osas Ighodaro), and others to form a robbery unit named The Armadas. They record some successes. But to make a film of this kind, there must be some conflict. The impressive thing here is that the conflict in the story is two-fold: it comes from both within the group and from outside of it. The unfortunate thing is that the screenwriting never rises to the occasion.

One of the ways in which this is the case comes through with Ahanna’s supposed high intelligence. Nothing the viewer sees really makes a case for this. Neither witty nor wily, Ahanna is more like a mild-mannered middle manager than some criminal mastermind. But given the gaps in characterisation, the film is well-acted, and Atta’s cinematography is often decent. One particularly gorgeous shot involves the Armadas silhouetted as they celebrate in Cape Town.

It’s a very beautiful shot, but how did they get to South Africa? Well, as I wrote, the filmmakers are in thrall to glamour, so viewers receive a crash course in touring South Africa where the reality TV star, Nengi, shows up in a laughably bad cameo. She’s signed to the company that is responsible for the film but you wonder if a film appearance she was clearly unprepared for is the best way for the producers to go about using their film as an avenue to advertise other parts of their business. If you ask me, my response would be, “I don’t think so.” In fact, one of the maddening things about Nollywood is its penchant for undermining itself with amateurish stuff of this nature. Is there really no script consultant in the industry that could tell the producers how a cameo can be tastefully done? A much better-handled guest appearance happens in the second act. It features a character from Living in Bondage in what seems like an attempt at creating a cinematic universe uniting both films.

I don’t think that the stories told by both Living in Bondage and Rattlesnake are compelling enough for their own universe, but I am willing to be surprised. I just hope the filmmakers reduce their over-indulgence and figure out how to boost the quality of their screenwriting. For now, all that should be said is that the new Rattlesnake is good to look at. Sadly, the film’s ambition is defeated by its script and the outsized focus on glamour by its producers.

My final grade: C.