Inspired

UNESCO predicted the Igbo language would vanish by 2025 but it’s become a global hit taught at Oxford, Harvard & Digital Spaces

On a regular school day at a junior secondary school in south-eastern Nigeria, an Igbo language teacher walks into a classroom and begins the lesson with a greeting.

When the learners greet her in unison, with “Good morning!” their teacher responds: “Mba, an Igbo!” (“No, in Igbo!”)

To which the students reply, “Ututu Oma.” (“Good morning’)

“Deal. Nodu ala, ka any malice,” (“Thank you. Sit down, let’s get started”) the teacher responds, again in Igbo.

Junior secondary school students are among the thousands of young learners in Nigeria and worldwide who are learning the language that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) in 2012 declared would be extinct by 2025.

In 2013, Emmanuel Asonye, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of New Mexico, explained that the sentiments of its speakers and bastardisation of the language were broadly threatening the language.

“It is a fact that Igbo people acknowledge that they exhibit a negative attitude towards their language. This includes both the educated and non-educated population. It is, an irony that those who claim that UNESCO’s prediction is untrue are among those who can neither read nor write Igbo – those who have no scholarly work on the Igbo language to their credit – those who boldly but ignorantly murder both Igbo and English language in their speech and writing,” he wrote, in the Journal of the Linguistic Association of Nigeria (2013).

The UNESCO announcement seems to have shocked those who use the language – one of the more than 500 spoken across Nigeria – into action and given the language wings, locally and globally. Ten years on, it is becoming a common language of instruction and study in the region, much as Kiswahili, another African language recently adapted for official use at the Africa Union, did in east Africa.

Igbo is now one of the five top languages in Nigeria and is spoken by an estimated 25 million people, mainly n the southeastern part of the country. In popularity, it comes second to Hausa, spoken by an estimated 50 million people, mainly in Northern Nigeria. Other languages include Yoruba, Hausa, Kanuri, and Ibibio.

Online communities have emerged to ensure its survival and spread from its cradle to the rest of the world – and new generations.

Igbo History & Facts, Igbo Dances, and Okwuid are some platforms on Twitter and Instagram promoting the Igbo culture and its language to the world. Others are, Learn Igbo for Kids, Igbo Amaka, and Igbo 101 by Genii Games.

Igbo mobile language apps have proliferated with many showing substantial download numbers, while websites such as igbotic.net, created by Maazi Okoro Ogbonnaya, an Igbo linguist, researcher, and historian, are also helping first-time learners to grasp the language quickly.

“The platform is designed bilingually. Additionally, I have been travelling, documenting the cultural and linguistic history of the Igbo and making the information available for the public through social media and blogs,” said Ogbonnaya, who believes that there must be deliberate efforts to keep the language alive.

“UNESCO is right. We can only prove their prediction wrong by taking action immediately. As a linguist, I believe that when a language is neglected by its speakers, it will become extinct. Many people cannot boast of speaking Igbo fluently. When a language is gone, culture is gone. It means that identity has gone too.”

Already in 2013, Asonye was seeing a reaction to the shocking pronouncement, which appears to have jolted the Igbo-speaking community into action.

“UNESCO’s prediction itself has awoken Igbo scholars and indigenes towards a greater conscious effort to keep their language alive, as several clarion calls are being made by many Igbo scholars for a positive attitude towards the language,” he wrote.

According to the UNESCO Atlas of The World’s Languages in Danger, “external forces such as military, economic, religious, cultural or educational pressures,” build a “community’s negative attitude towards its language, or into a general decline of group identity,” contributing to the demise of a language.

“Parents in these communities often decide to bring up their children in other languages than their own. By doing so, they hope to overcome discrimination, attain equality of opportunity and derive economic benefits for themselves and their children,” it states.

According to musician and self-proclaimed Igbo language advocate Ifechukwu Mercy Michael, a new, conscious effort to maintain the language is making it more dynamic and its popularity is growing amongst the youth.

“As long as people like myself exist, our language can never die. I infuse Igbo into everything I do; my music, interviews, campaigns, and style,” Ifechukwu said.

For decades after independence. Nigerian households and institutions widely regarded indigenous languages as being for the ‘ordinary and unschooled’. Those who spoke their mother tongues in schools where English was the language of communication and instruction, were punished.

English is the only official language in Nigeria. Urbanization, cross-cultural marriages, and migration have also played a role in the gradual demise of many of the country’s indigenous languages, especially among the youth. In 2012, Igbo, spoken by over 20 million people, had been in danger of going the same way.

But there are new champions of the indigenous African languages, promoting their use and preservation.

One of them is Onyeka Nwelue, Founder of the James Currey Society. Nwelue promotes the Igbo language through a collaboration with the African Studies Centre and the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages at Oxford University.

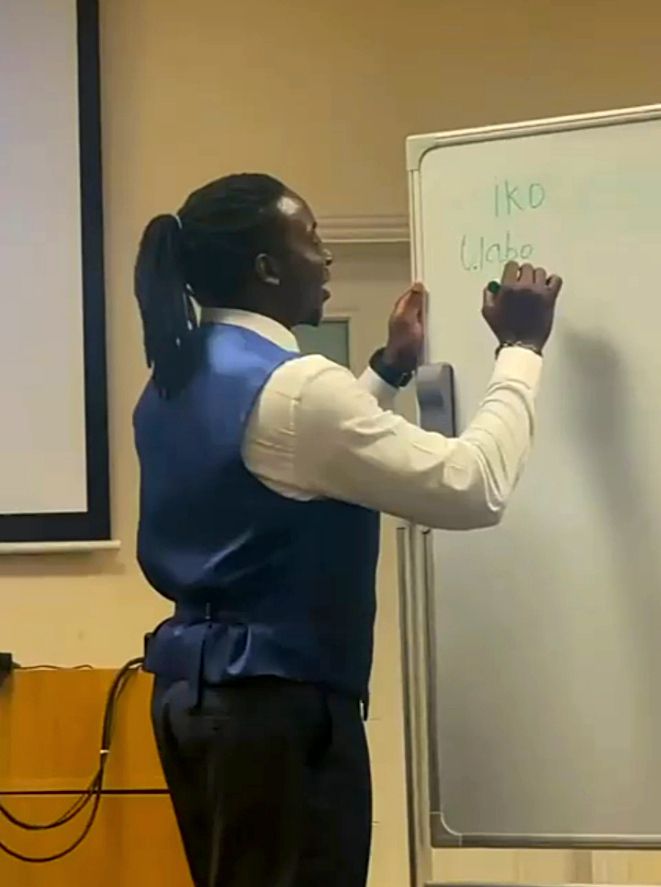

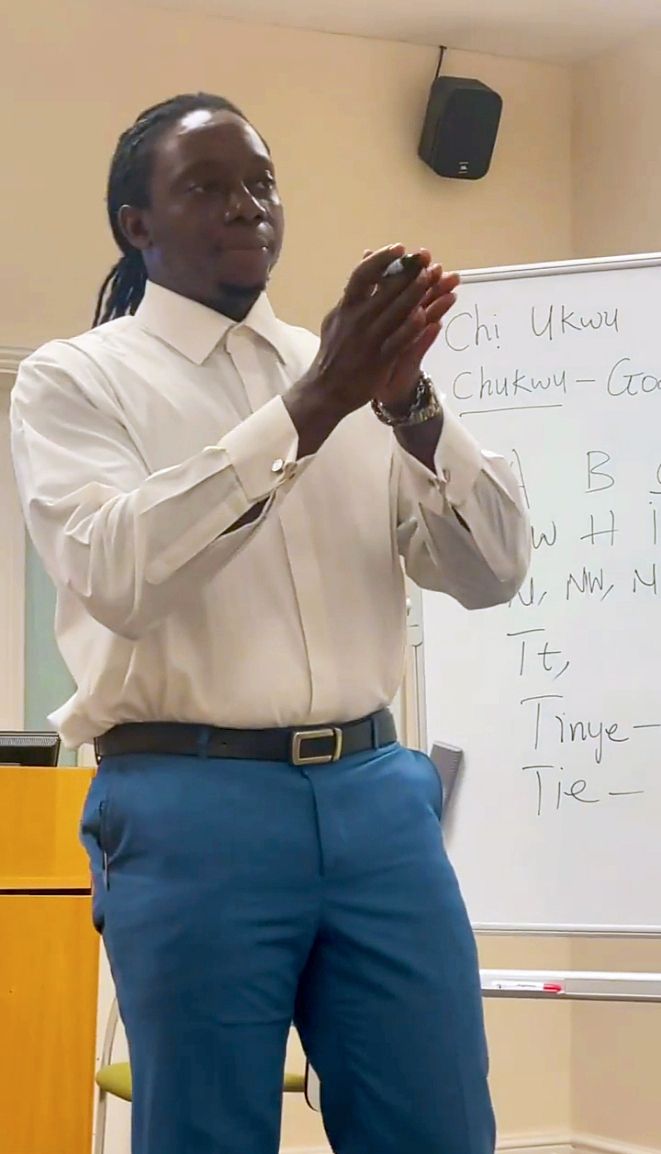

The society started offering Igbo language classes at the university in February. To ensure the programme was running smoothly, in February 2022, Emmanuel Ikechukwu Umeonyirioha was inducted as an Igbo language lecturer.

Sharing the news on Twitter, Umeonyirioha said: “This will be the first time the Igbo language will be taught at the university, made possible by the James Currey Society. History has been made.”

It is official that I am the first official Igbo Language lecturer at the number one university in the world, the University of Oxford. Our induction happened today by Marion Sadoux, Head of Modern Language Programmes, University of Oxford Language Centre. pic.twitter.com/OqFDdHrUkJ

— Emmanuel Ikechukwu Umeonyirioha (@lordibmbomb) February 17, 2022

In an interview with BBC Igbo, Nwelue said the drive for creating Igbo language classes at Oxford University was his desire for “whites to learn to speak Igbo, just as we learn English.”

For Adaku Jennifer Agwunobi, a post-doctoral researcher in Engineering Science at Oxford University, this was exciting news.

Born in the United Kingdom to Igbo parents, Adaku had visited Nigeria for the first time when she was ten-years-old, and the second time when she was twenty-three. Growing up, she mainly connected to her community through the Igbo highlife music her family had played in the house when she was a little girl.

While understanding her native language was easy, however, the problem was speaking it.

“I always struggled with speaking Igbo. It doesn’t sound right when I speak it because of my British accent. I had to learn to pronounce my (first) name properly,” Adaku said.

Adaku hopes Igbo will evolve from being taught by the James Currey Society at Oxford University to becoming a course of study in the university, just as Igbo has at top institutions in the United States, like Boston University, Yale University, and Harvard.

Across Africa, attitudes are also changing, as more Africans seek to reclaim their disappearing languages – the vehicles of their culture and identity.

“During my tour and the #AfricaEducatesHer campaign for the African Union International Centre for Girls and Women’s Education in Africa, I spoke Igbo in the countries I visited, although most people spoke French. Eventually, I related with the Igbos I met, and they were very excited to see and listen to me,” said Ifechukwu.

Already there is far greater awareness of the geographical spread of the language and its different dialects – and not just in Nigeria.

According to a report by Indiana University, “The Igboland is now situated in seven states of Nigeria (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo, Rivers, and Delta with a variety of dialects that include Ikwere, Etche, Ika, and Ibo). There is also a great number of Igbo speaking people in the Diaspora (U.S.A., Canada, Great Britain, Germany, and every part of the world).”

“If you go to any country, and an Igbo person isn’t there, just know that humans cannot survive there. There are Igbo descendants in Equatorial Guinea with a similar culture to Igbos in Nigeria. But they don’t speak exactly like us. The reason is that of a linguistic factor,” explains Maazi Ogbonnaya.

“In sociolinguistics, there is language contact and shift. Language contact takes place because of proximity between two or more languages. The Igbo tribe of Bioko, Equatorial Guinea had contact with others which influenced their language, and it shifted from the original Igbo form.”

Ikhide Ikheloa, Chief of Staff to the Board of Montgomery County Public Schools, Rockville, Maryland, believes that staying true to one’s culture gives true identity.

“Every language depends on its speaker for survival. That’s what gives it purpose and agency,” Ikheloa said.

“However, we’re a colonised people. We hold everything we do to the standard of the white man, so our food, language, and culture have become gentrified. Our children learn Chinese, Spanish, and other foreign languages, but there’s a need to reorient our way of life and the value of our languages. We can’t continue to be embarrassed about ourselves. At some point, our culture will become revived and fashionable again.”

Photo/Story Credit: Gabriella Opara for bird story agency