Inspired

This bio-engineer designed incubators “Made in Africa, for Africa” to reduce infant mortality rates

At the far end of the University of Yaoundé campus in Ngoa Ekelle, on the road to Melen, is the complex of the Ecole Supérieure Polytechnique de Yaoundé.

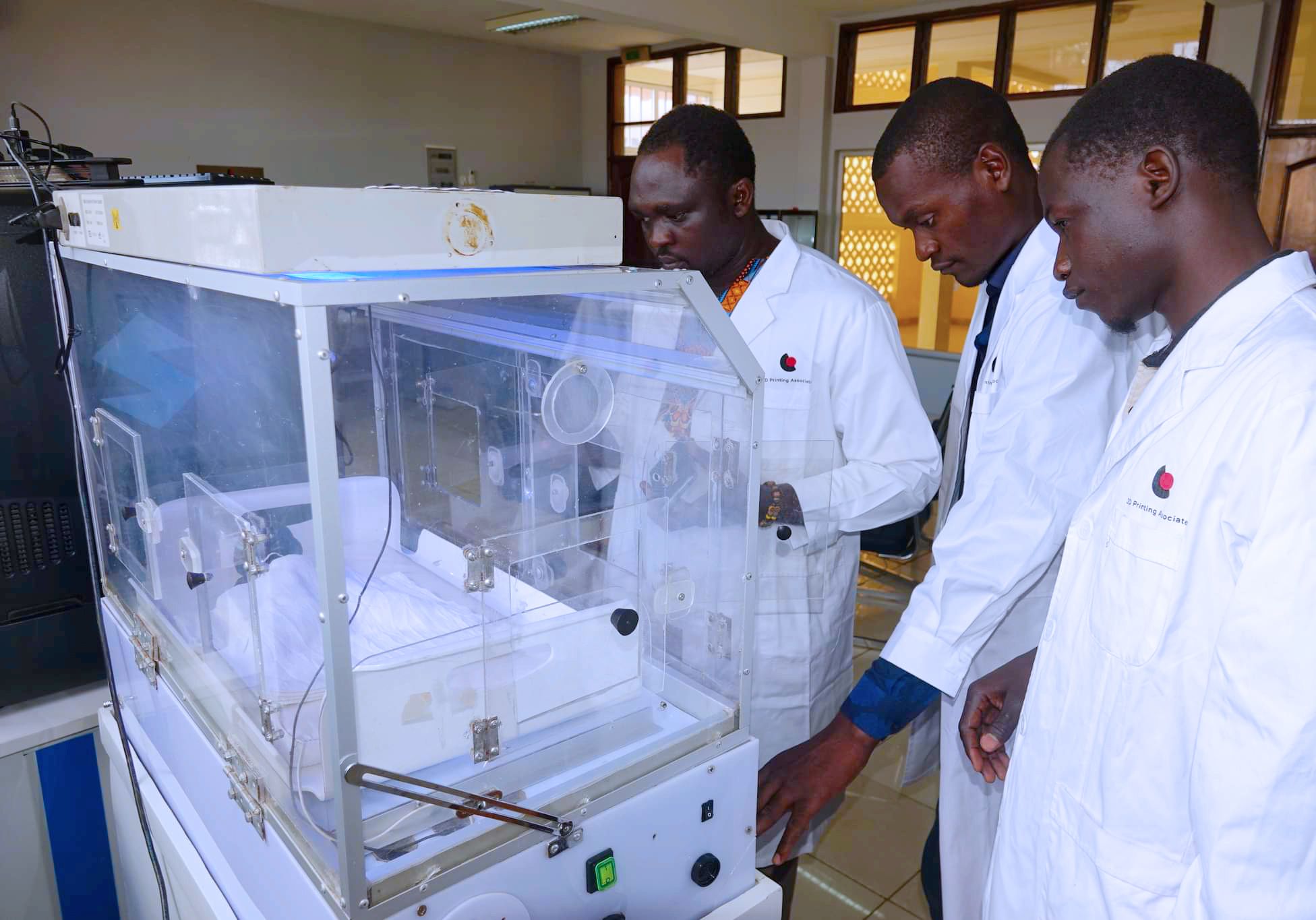

The complex is fully air-conditioned with large windows that admit a free flow of light. It houses 3D printers and other advanced equipment.

Since its start in 1971, the institution has trained more than 3,000 engineers and has been a driver of innovation.

On this day, in laboratory number 4, a squad of students is working under the direction of a man in a white coat. They are repairing medical equipment sent there for maintenance. Their leader, Stéphane Tabeu, is a 35-year-old engineer who is no stranger to innovation. He has designed a neonatal incubator to put an end to a tragedy that many Cameroonian families face far too regularly.

“Cameroon has only 100 neonatal incubators for several thousand health facilities. It is estimated that approximately 15,000 premature infant deaths could be prevented each year if the Cameroonian health system had adequate equipment,” Tabeu explained during a break from his teaching.

His passion for life-saving and healthcare-improving systems came from a seed that was planted in 2010 when, as a physical sciences student, he started an internship in biomedical equipment maintenance at Yaoundé University Hospital. There, he cultivated his skills in disassembling and reassembling all kinds of appliances, from vacuum cleaners, scales, and microscopes to blood pressure monitors, stethoscopes, and a variety of medical devices.

Shocked by the horrific statistics and stories of prematurely born infant deaths in his country, Tabeu vowed to come up with a solution. Why not make his electrical circuits and operating systems and then put them in an incubator made of local materials?

After four years of toil, “sweat and insomnia”, he came up with his answer, the “Mouboua 1401”, the first neonatal incubator completely designed and built in Cameroon.

“The first difficulty was obtaining electronic components that are not available in Cameroon. I started to collect and recycle old components that I could find here,” he said.

Because he didn’t have enough money, Tabeu used a big chunk of his salary to pay for his trip.

“I bought all the necessary local products and imported electronic components for the control board,” he continued.

Baby Incubators are devices designed for premature newborns who have not yet fully completed the development of their breathing organs towards autonomous breathing.

“Breathing is the main issue for prematurely born infants,” explained Dr Isabelle Mekone, a paediatrician at Yaoundé General Hospital.

Incubators must provide both oxygen and warmth in a completely sterile environment. They are highly technical and have to be completely reliable. They must also continue to function during power outages.

The device is also key to addressing several newborn diseases by way of phototherapy, a technique that exposes the baby to light to help slow the progression of jaundice and other ailments. Tabeu’s Mouboua 1401 is also adapted to the local environment, thanks to some extra features. This includes mobile interactivity, whereby real-time monitoring of the newborn (movements, temperature, and heartbeat) is possible via a remote control screen or a cell phone.

It is also powered by both electricity and solar energy and is capable of withstanding power cuts for a week, thanks to powerful batteries.

Local production would address the issue of importing devices that are extremely expensive to buy and repair.

“An incubator that is bought in Europe or Asia is usually between 25,000 and 50,000 US dollars, while this specimen will cost a maximum of 12,500 dollars,” said Tabeu.

Since 2014, the Mouboua 1401 field testing unit has been stationed at the Yaoundé University Hospital, where the bioengineer got his start and where five of the devices are now in service. The result of his painstaking work has been validated by the medical community.

“The incubator has received a certificate of conformity at the university hospital where it is in permanent use and gives ample satisfaction,” says François Kono, a biomedical engineer at Yaoundé University Hospital.

Tabeu’s plans to build a production line developing the incubators at a rate of thirty per month faced difficulties after a promised US$ 400,000 credit line from a government institution supporting small businesses failed to materialise.

“He is a young entrepreneur who should be known. He is part of the young people who, through their initiatives, are showing that Africa has a bright future and that this continent can rely on its youth,” said Mariette Bissene Moulongo, coordinator of the project at the Ecole Supérieure Polytechnique de Yaoundé.

Today, Tabeu divides his time between teaching physics in high schools, completing a PhD thesis in mechatronics and continuing to develop his incubator—as well as promoting food and clothing products “made in Cameroon”.

Local hospitals continue to send their broken appliances to Tabeu and his team for repair, and he continues to work on upgrading his invention. So far, he has refused to abandon his dream of producing and marketing the incubator in Africa and even globally.

Story & Photo Credit: Irene Mbezele and Patrick Nelle for bird story agency