Movies & TV

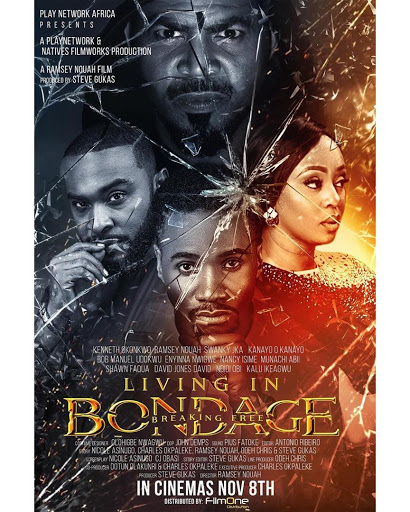

Dika Ofoma: Living In Bondage And The Brotherhood

Brotherhood, however, is never always a cry for help. Sometimes, it’s a welcome hug at the bus park, a competitive race home, shared memories, and a phone call bearing the most exciting news. Nnamdi and Tobe’s love story would forever stay in my heart and it was my highlight of Living In Bondage: Breaking Free.

One of the most interesting and recurring theme in the Living In Bondage films (original and sequel), is brotherhood, and the romantic affair that it is. By brotherhood, I do not mean the fraternities. I’m talking of the brotherhood of Nnamdi Okeke (Swanky JKA) and Tobe Nwaorie (Shawn Faqua) in the sequel, Living In Bondage: Breaking Free, and that of Andy Okeke (Kenneth Okonkwo) and Paulo (Okey Ogunjiofor.) I’d argue wherever that the brotherhood of Nnamdi Okeke and Tobe Nwaorie is the sequel’s main love story. Their relationship made me think of Keside Anosike‘s apt description of what the brotherhood is. Keside’s description:

One of the most interesting and recurring theme in the Living In Bondage films (original and sequel), is brotherhood, and the romantic affair that it is. By brotherhood, I do not mean the fraternities. I’m talking of the brotherhood of Nnamdi Okeke (Swanky JKA) and Tobe Nwaorie (Shawn Faqua) in the sequel, Living In Bondage: Breaking Free, and that of Andy Okeke (Kenneth Okonkwo) and Paulo (Okey Ogunjiofor.) I’d argue wherever that the brotherhood of Nnamdi Okeke and Tobe Nwaorie is the sequel’s main love story. Their relationship made me think of Keside Anosike‘s apt description of what the brotherhood is. Keside’s description:

“Brotherhood is a sacred entity. And with everything that is sacred, it has a fundamental purpose of changing or destroying one’s life. Growing up, you are convinced that love was wired in the blood- perhaps the same hook of a nose or spread of forehead. But then as you grow into yourself and navigate the overwhelming adult world, you find out that it is more than the similarity of your looks. That you have survived the worst because your brother was there to give a hug, to wait outside while you cried over a hurt, to give you space to not get lost in but to breathe well again, and then, if you are lucky, to tell you that his life has a purpose because you are in it with him.”

Both films challenged the traditional notions of who a brother is. A brother could be blood or a brother could simply be a brother. Nnamdi and Tobe were both blood and brother. Having grown together and raised by the same people, they had grown thinking of themselves as nothing but brothers, it did not matter if they came from the same loins or if they had suckled the same breasts. They were brothers, not because their relationship had become something beyond mere cousins, but because they had forged for themselves a relationship that was divine and wholesome. We saw them come through for each other whenever the storm struck. And this is what I think of brotherhood: a crag, a fortress for times of distress.

When Tobe bashed their father’s car, Nnamdi had taken responsibility for it. Because he knew that it would cause their parents (who are actually his Aunt and Uncle) greater displeasure if they’d known that Tobe did it. When Tobe enquires from Nnamdi why he’d done it, Nnamdi’s response is, “I don’t know. We will get through this. What you go through, I go through. You didn’t bash the car, we bashed it”. Now, read Keside’s description of what brotherhood means again and tell me if this doesn’t tug your heartstrings.

When the brotherhood of The Six, the other brotherhood in Living In Bondage: Breaking Free, requested for a sacrifice of the one he loved most, I thought it was very naïve of Nnamdi to believe that it was Kelly (Munachi Abii) they wanted.

Humans tend to place greater worth on amorous feelings over platonic feelings. So for Nnamdi, the human he loved most had to be a woman he shares great chemistry with, kisses, a musical bond, and had been sexually intimate with. Not the human, the man, he’d weathered through many storms with. But the devil knows better. When Nnamdi arrives Richard Williams’s (Ramsey Nouah) home to plead with him that he couldn’t sacrifice the woman he loves, Richard Williams tells him to send the head of any loved one. Tobe arrives at Nnamdi’s apartment at the tick end of the clock. The devil hungers more.

In that scene, or rather the scene before that which forms the climax of the film, both set in Nnamdi’s apartment, it is with Tobe that Nnamdi would share the details of the quagmire he was in. Something he’d been unable to do with most beloved Kelly. They share a bottle of beer and Tobe advises that he returns home, to Owerri. That things would be better. Here, it is Tobe who reminds him that he’s his brother. “Nna, I’m your brother. Your blood. Till the very end.” Being arguably the film’s most emotional scene.

What this vulnerability from both men allows for is a humane look at men. What that scene does is that it humanizes men in a world where men are ridiculed for a masculinity that does not allow for tears and weeping, and also shamed for exploring those emotions. Yes, men can cry while doing the most ‘masculine thing’ like sharing a bottle of beer.

With the knife over Tobe’s head, Nnamdi is reminded of who he wants to kill by Tobe himself. “I’m your brother. Your blood”. (The reiterations of “I’m your brother. Your blood” may have seemed redundant and needless but we see its purpose and culmination in this climactic scene.) Nnamdi is unable to take his own blood. It’s suicidal. Since killing Tobe tantamounts to taking his own life, Nnamdi takes his instead. And in that moment, the filmmakers create a visual representation of what it means for one’s life to flash through them; Nnamdi goes through his life’s fondest memories and we see that the most were those with his brother.

Nnamdi survives the knife stab. I’d like to think that he was fully resuscitated by the hug from brother. And that signature shake from both in that hospital room, shows a much deeper connection than the kiss from a lover. Than the kiss from lover Kelly.

Nnamdi and Tobe’s brotherhood is aspirational and so also is Andy Okeke and Paulo’s. Andy Okeke, in the 1992 Living In Bondage, tired of a life of penury, would solicit a deliverance from classmate and friend, Paulo. In their first meeting at a restaurant, we find that the dynamics of their relationship had gone beyond just former classmates and just friends. They related like brothers. In fact, they referred to each other as Nwanne – siblings. Nwanne, when transliterated, means Mother’s child. And it was out of love and the obligations of brotherhood that Paulo had obliged Andy and led him to the other brotherhood where he’d find wealth, although through unorthodox means. A return to Keside’s description of what the brotherhood is and tying it to Andy and Paulo’s brotherhood shows that it both changed and destroyed Andy’s life – unshackling him from the fetters of poverty whilst also plunging him into a life of heinous sins and mental derangement – and that this ‘destruction’ of his life is still in line with the functions of a brotherhood.

Brotherhood, however, is never always a cry for help. Sometimes, it’s a welcome hug at the bus park, a competitive race home, shared memories, and a phone call bearing the most exciting news. Nnamdi and Tobe’s love story would forever stay in my heart and it was my highlight of Living In Bondage: Breaking Free.