Movies & TV

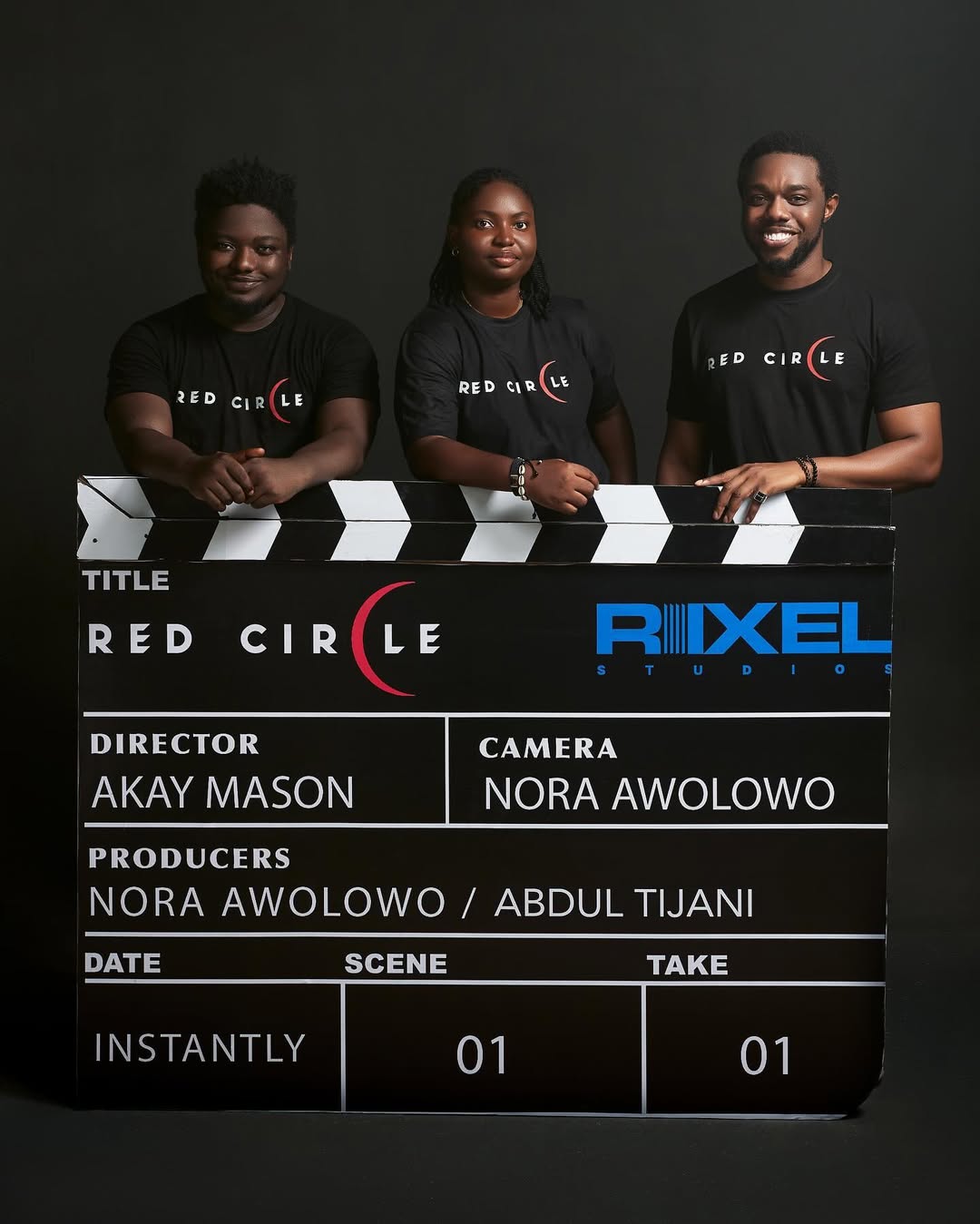

Nora Awolowo on Breaking Nollywood’s Box-Office Record at 26 & Being A Voice for Young Filmmakers

At 26, she’s broken Nollywood’s box-office record, become a voice for young African filmmakers – and she’s only just getting started.

I couldn’t think of a better way to begin this essay about my conversation with Nora Awolowo than with this: I wore a red T-shirt to speak with her. I could make it sound more dramatic by saying I scoured my wardrobe for it, but truthfully, it’s the only red clothing I own. Still, nothing could have been more fitting for a conversation with the film producer and multitalented media creative who has made red the colour to see on your social media timelines, and, in this case, even in my dreams.

Call it commitment or coincidence, but for this conversation, red felt like the only right choice. Really, what else could I have worn?

Nora had just got back from her UK run for “Red Circle” — London, Milton Keynes, Manchester, Birmingham — all in one week. She’s been busy. Booked. Tired. But the good kind of tired. The kind most people would pray for, when exhaustion feels more like a badge of honour than a burden. And how could it not? The smiles, the excited chatter, the people who showed up for the film and couldn’t stop gushing about it… that’s the stuff that keeps her going. For Nora, that’s the real win.

But Red Circle wasn’t just winning hearts; it was making history too. In its opening weekend, the film pulled in an impressive ₦33.8 million. By the end of the second weekend, that figure had leapt to ₦74.5 million, and by the third week, it had crossed the ₦101.8 million mark.

Everywhere you looked, there she was. Nora Awolowo in a red dress. She laughs about how much the media loves that photo, though she still can’t figure out why. But there it was, splashed across front pages, paired with the headline that said it all: “Nora Awolowo Becomes the Youngest Filmmaker to Hit ₦100 Million at the Nigerian Box Office.”

I gave Nora Awolowo her flowers, as it should be done, and told her I was pouring a truckload of congratulations on her. She immediately shifted the focus to the work: the long nights, the team’s heavy lifting, the intentional push to get the film to perform. She was already explaining the process when I interrupted her.

“Hold on. We’re still in the congratulations part. What does it feel like?”

At first, it hadn’t felt like much, she admitted. She was seeing the numbers, scrolling past the headlines, but it didn’t occur to her to stop and acknowledge the weight of what she had done, at 26, and as a woman in an industry where wins like this are rare. A friend had to sit her down and say it plainly: this is history.

Nora isn’t one for champagne toasts. She’s already moving on, “tidying up her desk,” thinking about the next project. But in the quiet of her own space, away from the noise, she lets herself feel it.

“I sit in the stillness of my house, in the corner of my room, and I’m grateful,” she said. “You don’t get to see that often, especially in Nigeria’s economy.”

The economy hasn’t exactly been kind. Cinema tickets aren’t the first thing on anyone’s list when streaming is just a click away. Nora knows this, and she’s deeply grateful that people showed up. She credits that to the love for the film and the hard work her team poured into marketing, even with a limited budget.

She’s quick to admit that cinema attendance has been dropping, and marketing films in Nigeria has become almost formulaic: you dance, you go viral, you sell tickets. She isn’t against that. In fact, she laughs and tells me, “Nigerians are exhausted; they just want to be entertained.” But for Red Circle, she and her team wanted balance: give people fun and something serious enough to stick. That’s how the now-iconic red circle symbol, perfectly echoing the film’s title, became the centrepiece of their strategy.

“I logged into Twitter one day,” I told to her, “and suddenly everyone had red circles in their bios. I thought, what’s going on?”

She grinned when I said that. That exact reaction — curiosity, the thing that sparks conversations and, eventually, action — was the goal. “You know the way APC posters were everywhere in Lagos, and people joked about seeing Babajide Sanwo–Olu in their dreams? I wanted that same effect,” she admitted.

The strategy worked because it wasn’t just marketing. It felt like belonging. The waitlist campaign, with the hashtag #JoinTheCircle ⭕️, pulled people in. Personalised digital IDs became community cards, little symbols of “you’re in.” Newsletters kept the circle alive, and with them came the thrill of being part of something larger than yourself.

Still, for Nora, it was never only about community. She wanted something that would outlive the film, something people would remember years from now. And for that, she says she’s grateful. For the team who believed, the cast who gave everything, and everyone who pushed for its success like it was theirs too.

Success looks like Nora Awolowo’s media career. An AMVCA win, multiple award nominations, and a record-making film, yet she isn’t stopping. She still wants to tell stories the average Nigerian can connect with — shaped by what she sees every day and what she believes must be told. Nothing abstract, nothing esoteric.

In her award-winning documentary “Nigeria: The Debut,” she takes us back to 1994, capturing the excitement of the Super Eagles’ first World Cup appearance. Archival footage blends with interviews from Sunday Oliseh, Stephen Keshi, and Emmanuel Amuneke, creating a vivid portrait of that historic moment.

There is “Life at Bay,” which moves past the famous Tarkwa Bay beaches into the villages to tell the stories of the women who live there. And “Baby Blues,” which turns its gaze to postpartum depression, a struggle many Nigerian mothers face after childbirth.

Nora Awolowo makes films for everyday Nigerians, and she’s obsessed with the details of their layered lives.

“My works are inspired by everyday life, everyday people,” she says. “I take walks and watch how people react to things, what influences them, what Nigerians get happy or angry about. Even how they behave at the fuel station tells you something.”

“I want my films to feel relatable, to show that we, as people, are flawed and multi-dimensional.”

So if you ever see Nora at Tejuosho Market, weaving through stalls of lace and damask, she’s not just shopping. She’s watching the way you haggle with the fabric seller, storing gestures and snippets of conversation for a future film.

“I also like to tell stories about women,” she adds. “I’m fascinated by us. Our lives are so versatile. You can’t fully explain it. You need to be a woman to understand womanhood and the limitations placed on us. The least I can do is use my work to show those realities, for women and for Nigerians.”

That same love for women’s stories led her to bring Bukky Wright out of her long film hibernation. The veteran actress, who had been away from Nigeria and the spotlight, was a deliberate choice for Nora, almost like destiny fulfilled.

“It was a dream come true for me,” Nora says quietly, the excitement still audible in her voice. “She had been in my long-term vision for years. Her role brought a certain depth to the film, and just having her on set every day made me deeply happy.”

Most filmmakers trace their path back to film school or a childhood spent dreaming of life behind the camera. Nora Awolowo’s story is less obvious. She was the best graduating student in her accounting class, aspired to become a banker, not a filmmaker. Nothing in her early years pointed to this life, apart from the ritual of renting CDs, watching them with her family, and taking turns with neighbours to see what came next. Those nights, though ordinary at the time, planted the seeds.

“I grew up wanting to be a banker,” she recalls. “Then came the ASUU strike, and I realised I was fascinated by architecture. I’ve always been obsessed with lines, shapes, and structure. A friend asked what we could do with all that time, and when I talked about my fascination with architecture, she said photography was related, it’s all about composition. So I started taking photos with my phone, learning as I went.”

That curiosity pulled her deeper into visual storytelling. Soon, casual photography turned into a serious career path, with filmmaking courses and a clear decision to commit to the industry.

Now, Nora is determined to push for change. “I want more women in technical roles,” she says. “Not just as producers or directors, we already have many there, but as cinematographers, sound leads, and other behind-the-scenes roles. Women are naturally attentive to details. We need more of that, and not just in Nollywood.”

Her advice to younger creatives is as blunt as it is hopeful. “Lock in,” she says. “Ignore the noise, ignore the whispers. Be true to yourself. Don’t try to fit in. The universe rewards doers. Just do.”

When I ask what’s been bringing her joy lately, besides a bottle of whiskey (the mere mention of which makes her exclaim like I’ve uncovered a secret), the success of Red Circle, and the thrill of new projects, she laughs. Her social battery, she admits, has run low.

“It’s like I’ve spent all my social battery for 2025, so I’m recharging. I’ve been listening to a lot of podcasts, especially with African outliers who are practical and actually getting work done. I don’t listen to ‘aspire to perspire’ people. I want to hear real, realistic stories of people who’ve been through what I’m going through and still made it.”

“Books, podcasts, listening to a lot of interviews and yeah, drinking whiskey!”

***

Photos by Nora Awolowo